Sweating Through a Gym’s Gender Barriers

As I walk into the gym, my nostrils flare at the smell of sweat and old iron. My eyes itch from the grip chalk in the air. My body reverberates with the clangs of hundreds of pounds being dropped repeatedly on the floor. Regulars, almost all men, greet me with a wave and a “Good morning, Doc!” as I approach the squat racks. My lifting partner cracks a smile, and we get to work, with our concerns left at the door. This place is my sanctuary. But for a time, it was my hell.

As a biological anthropologist, I study how humans cope with extreme conditions and push themselves to the limit. I began powerlifting to get in shape for fieldwork studying outdoor enthusiasts in the American Rockies. It became a passion. But being a female powerlifter isn’t easy, and the difficulties rarely have to do with lifting.

Though female participation in strength sports is on the rise, powerlifting remains a hypermasculine territory. The few women who dare to break in must navigate complex and taxing rites of passage.

My three-year journey at a powerlifting gym pushed me to my physical and emotional limits. Eventually, with some help from the anthropological perspective, I recognized how this journey changed me and how I made small changes to the sport’s gendered culture, one person at a time.

In 2016, I started a new job in a new state, so I decided to switch from campus gyms and YMCAs to a serious lifting facility. When I arrived at this gym, I thought I had found my weightlifting sanctuary.

This was a banging and clanging gym, made for powerlifters. Shelves displayed a vast array of supplements with aggressive names like T-UP and BOOM STICK, all promising to drastically boost strength and virility. The large weight room was filled with equipment marked by dents, chipped paint, and spots of rust—clear signs they had been subjected to heavy use and abuse.

I stepped into that room armed with a rigorous training program and dreams of hitting lofty personal records. However, I was quickly deflated, diminished, and demeaned. Instead of walking into a haven of heavy lifting, I had entered a crucible of toxic masculinity.

I was almost always the only woman there, and I endured a near-constant stream of unsolicited advice on my lifting form and comments about my body. Once, a regular came up to me and said, “You are built like a brick shithouse. Whew, if only I were a younger man.”

Sometimes I wanted to lift heavier than I was comfortable doing alone and needed a spotter. Despite my clear instructions (“touch only the bar, not the body”), men unnecessarily touched me. Or they stood so close that I could see—and smell—up their shorts.

These interactions felt threatening because they were meant to be threatening. The posturing, inappropriate comments, and unnecessary touching are rooted in two paradigms familiar to many anthropologists: muscular Christianity and gendered spaces.

Muscular Christianity arose in the Victorian era as a response to the perceived feminization of the Anglican Church and expanding roles for women in the public sphere. The movement fathered organizations such as the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA). At the sinewy core of muscular Christianity is the idea that sculpting one’s body and building strength is a demonstration of masculinity and strong moral fiber. It is therefore almost a patriotic duty to display your superiority over those who do not follow suit.

This ethos has become so normalized in the U.S., wrote American anthropologist John MacAloon, that “it fails to stand out as anything unusual. I would suggest that not just the sports departments but the entire moral economy and discourse of American public schools … remain largely derived from the legacy of muscular Christianity and the games ethic.”

Wrapped into this is the creation of gendered spaces in sports. Sports that demand strength (football, powerlifting, etc.) are traditionally meant for men, while those that rely on grace and calisthenics (dancing, figure skating, etc.) are meant for women.

Even territories within a gym are highly gendered. The weightlifting zones are male spaces; the aerobic areas are female spaces. The way these domains are constructed and used expresses attitudes about gender. In my gym, the area one might begrudgingly call the cardio room—where women might have escaped the macho vibes—held only a handful of threadbare and often broken treadmills alongside token, unused ellipticals.

Entering the heavy lifting area of my gym meant I was trespassing on two accounts: I wasn’t built like someone who ascribed to the ideal of muscular Christianity, and I wasn’t a man. As such, I was treated as an outsider and regularly demeaned.

It got to a point that I asked myself, Do I want to lift heavy, engage with other lifters, and endure harassment? Or do I just put on my protective “fuck-off” headphones, lift light reps, and avoid inappropriate behavior? Increasingly, I chose the latter. For almost a year, my progress and my mental health suffered.

Over time, I entered what I can now call—with a distant, anthropological view—a liminal or transitional phase. I wasn’t part of the gym culture, and I wasn’t on the outside either. There was still the occasional intimidating behavior, but for the most part, the men ignored me, and I avoided them.

With less harassment, I started to find joy in lifting again. My strength was progressing but so was my isolation. This went on for months. Then things suddenly changed.

I was bench pressing and (sigh) needed a spotter. So, I asked Hannibal, one of the morning regulars, a huge guy who lined up a buffet of intra-workout supplements on the reverse hyperextension machine. [1] [1] Pseudonyms have been used to protect people’s identity. Though Hannibal didn’t spot me the way I asked, he didn’t stand so close that I got a forced telescopic view up his shorts. I thanked him. Then something odd happened. Hannibal, who never said a word to me before, sat on a bench and struck up a conversation.

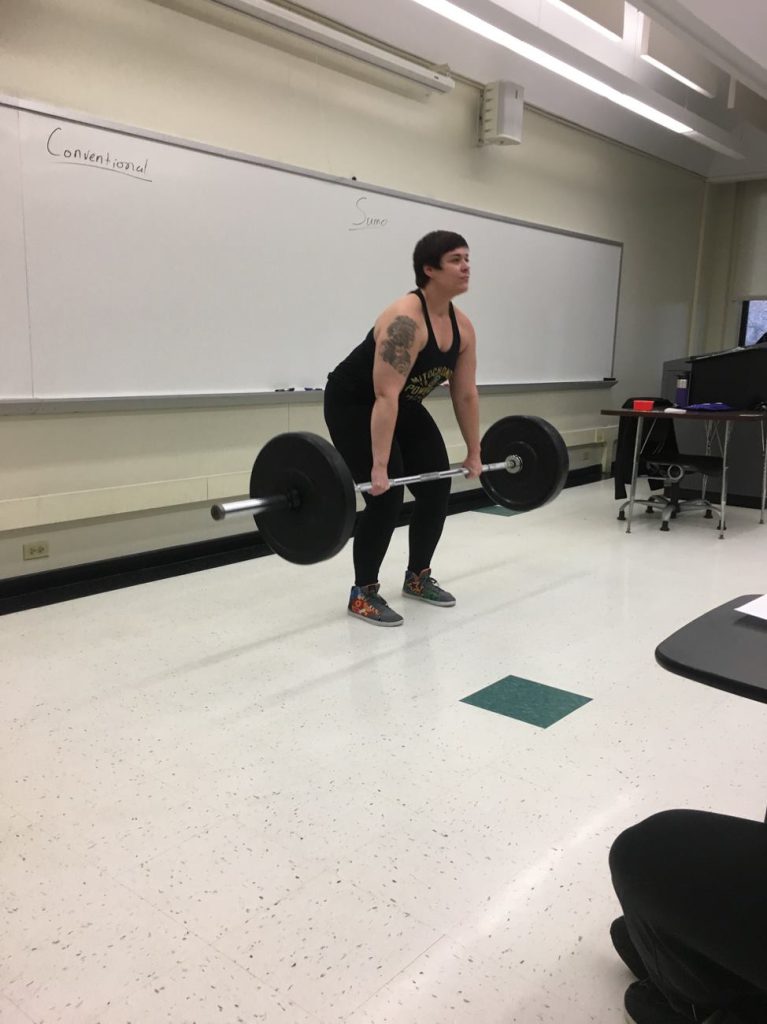

Not long after that, I was deadlifting a heavy weight for a fairly high number of reps. On the last rep, I dropped the weights aggressively. Max,* another regular, asked, “Do you compete?” I coldly, perhaps even hostilely, responded, “No!” As I walked away, he said, “You should.” And that was it. He didn’t comment on my form. He didn’t say anything inappropriate. He treated me like a “real lifter.” From day one, that was all I wanted—and it took over a year to get it.

Later I asked Max and Hannibal: “What changed? Why did you start talking to me?” They both gave the same answer: I had put in the time and work. I had gone through some unwritten and undefined rite of passage that I wasn’t fully aware of, and I had come out the other side.

Max and Hannibal slowly became my friends. Conversations got longer and ranged in topic from books and movies, to what I taught in my classes, to the feasibility of using bee stings as a performance enhancing drug we dubbed “Stang.” Trust also grew, particularly with Max, who became my regular lifting partner. I hardly ever wore headphones, and my strength and performance drastically improved. The gym was truly becoming a sanctuary.

Two milestones defined my social progression.

Milestone 1: Max asked me to spot for him. Mind you, Max holds a very traditional, gendered view of weightlifting. Before I started spotting for him, he had said to me, “I would feel emasculated if my wife lifted heavy,” as though her strength (or that of any woman) might diminish his own. Max likely never saw himself asking a woman to spot for him, much less having a woman become his lifting partner. So when I first spotted for him,

Instead of walking into a haven of heavy lifting, I had entered a crucible of toxic masculinity.

I was beyond excited. I couldn’t believe I and my strength were trusted enough to be considered a suitable spotter. From that point on, we became invested in each other’s progress.

Milestone 2: During what I wistfully call the Summer of Squats, I decided to add 50 pounds to my squat in three months. It was a nearly impossible goal, and I worked incredibly hard. When the day came to test myself, I silently walked up to the bar. Max took up the spotting position behind me. Without my asking, the gym owner and another regular appeared on either side of me to form a triangle of unspoken support. I hit that squat. And when I re-racked the weight, I fell to the ground sobbing. (I’m welling up as I write this.) As I looked up, Max turned away with tears in his eyes. He may deny it, but he was as invested in that lift as I was.

From almost that moment on, I became an institution in that gym. Everyone greeted me when I arrived. No one commented on my form or made inappropriate remarks. People asked me for advice. They genuinely wanted to know how I was, and I genuinely wanted to know how they were.

What I experienced has been observed by anthropologists everywhere. British anthropologist Victor Turner noted that rites of passage are characterized by three stages: separation, a liminal phase, and communitas—fellowship and belonging. He described a rite practiced by the Ndembu of Zambia in which an aspiring leader isolates himself in a hut (with one wife), endures pain and ritual insults, then is welcomed back into the community with a newfound high status. In my case, I was ignored and isolated myself with headphones, endured pain and ritual insults while proving my worth through deadlifts, and finally achieved a form of communitas—bonding with gym bros.

Not all of my changes were good. Turner points out that people achieve communitas by adopting a group’s social norms. I firmly believe part of the reason I was accepted was because of my willingness, conscious or unconscious, to participate in some toxic masculine behavior. I mocked people for not hitting parallel on squats and joined the group in laughing at a guy filming himself doing shoulder shrugs. I was territorial over my favorite squat rack and intimidated people away from it. I also found myself giving people unsolicited lifting advice.

I am not proud of these things, and now I actively work to tamp down any urge to participate. That’s important because I am moving to an academic institution in a different city, and I will have to start all over again in a new gym.

My profound sadness about leaving this gym forced me into a state of reflection. What changed? Why? Wait, did anything actually change?

I certainly changed. I have a negative body image, but in that gym, I came to see my body not as a collection of unsightly flaws but as a source of current and untapped power. I loved my body for what it could do, and it made me question the ideal female body type women are told we should strive to achieve.

In the process, I became living proof—to both men and women around me—that women can be, and are, strong. There are countless examples of strong women in professional sports, but it’s easy to brush them off as freaks of nature. It’s much more difficult to deny—and to accept—women’s strength when it’s in front of you.

For that reason, female presence in hypermasculine spaces is critically important. After I began spotting for Max, I became a go-to spotter for a number of other men. One of them said he asked me because “I know you’re a for-real lifter. Some of these other guys, I’m not so sure.” That spoke volumes because it showed he was focusing on my abilities, not my gender.

My presence also helped the few other women in the gym. One newcomer was struggling, and I asked if she wanted help. She seemed grateful, so Max and I took her under our lifting wings. It took me over a year to have a positive experience with the gym’s heavy lifters, but because of my efforts, one woman was able to have a positive experience early on.

But shifting these gender norms, given the weight of thousands of years of tradition, is slow work. As my impending move approached, Max complained about having to find a new spotter. I was ribbing him and told him he might find another female partner. “Not one that can spot for me,” he said. His response threw a bucket of ice water on my thoughts that I was trailblazing a better future for female lifters in that gym.

A study on gendered spaces proposed that macho men would eventually accept women and gay men in the gym because they would no longer see them as threatening strangers. The study posited that this would change attitudes toward women and gay men in general. However, I disagree that acceptance of an individual necessarily confers acceptance on a group. I hadn’t changed Max’s mind about women in strength sports; I had only changed his mind about me.

I hope future female lifters will be more readily welcomed into that gym because of the changes I made. But Max’s comment was a sobering reminder of the steep uphill battle women (and all marginalized groups) face breaking into traditionally masculine spaces. Change comes about slowly, one person at a time, like trying to tear down an age-old mountain one fistful of rock a day.