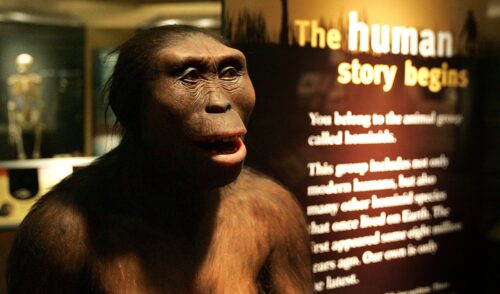

These days, a mention of cyborgs often conjures images from a science fiction future: robot arms and legs, infrared eyes, and other modified humans. However, we don’t need to look into the future to find cyborgs. In many ways, people today are already cyborgs. We are deeply intertwined with technology—from the clothes we wear to the structures we live in. But when did our relationship with technology start? Who was the first cyborg?

These questions take us from the present to the deep past, with host Eshe Lewis joining Cindy Hsin-yee Huang, a Paleolithic archaeologist, on a journey to ponder cyborg anthropology, tool use, and the relationship between our ancient hominin ancestors and their technologies.

Cindy Hsin-yee Huang is a doctoral candidate in the School of Human Evolution and Social Change at Arizona State University and affiliated with the Institute of Human Origins. Cindy is a Paleolithic archeologist, with a focus on stone tools and cultural evolution. Her research, supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, uses stone tools in the archeological record to investigate large-scale patterns of innovation and cultural diffusion during the ancient past. This work helps us understand how technology impacted, facilitated, and reflected human evolution, migration, and social interactions.

Check out these related resources:

SAPIENS: A Podcast for Everything Human is produced by House of Pod. The executive producers were Cat Jaffee and Chip Colwell. This season’s host was Eshe Lewis, who is the director of the SAPIENS Public Scholars Training Fellowship program. Dennis Funk was the audio editor and sound designer. Christine Weeber was the copy editor.

SAPIENS is an editorially independent magazine of the Wenner-Gren Foundation and the University of Chicago Press. SAPIENS: A Podcast for Everything Human is part of the American Anthropological Association Podcast Library.

This episode is part of the SAPIENS Public Scholars Training Fellowship program, which provides in-depth training for anthropologists in the craft of science communication and public scholarship, funded with the support of a three-year grant from the John Templeton Foundation.

In Search of the First Cyborg

[introductory music]

Voice 1: What makes us human?

Voice 2: A very beautiful day.

Voice 3: Little termite farm.

Voice 4: Things that create wonder.

Voice 5: Social media.

Voice 6: Forced migration.

Voice 1: What makes us human?

Voice 7: Stone tools.

Voice 8: A hydropower dam.

Voice 9: Pintura indígena.

Voice 10: Earthquakes and volcanoes.

Voice 11: Coming in from Mars.

Voice 12: The first cyborg.

Voice 1: Let’s find out. SAPIENS: A Podcast for Everything Human.

Eshe Lewis: Without my glasses on, I can’t see. OK, I can see, but it’s mostly just the blurry outlines of my surroundings. I have a high prescription. I’m very nearsighted, so I need my glasses to drive, read, and make out the details of anything more than about 10 inches in front of my face. Without my glasses, life would be very different and a lot more dangerous. But ever since I met Cindy Hy Huang, a SAPIENS fellow and cyborg enthusiast, I’ve wondered how many people are like me: reliant on something other than our own bodies to navigate the world. In this episode, we join Cindy Hy Huang on her search for the first cyborg.

[music]

Cindy Hy Huang: What’s your cyborg story? I have a digital calendar that keeps track of all my meetings. One day, my calendar didn’t synchronize properly across my devices, and I missed nearly all of my meetings. It was a stressful, panicky day full of apologies and anxiety. And in that moment, I realized how thoroughly my brain and my very person were inseparable from my technologies. I’m Cindy. I’m a graduate student, a prehistoric archaeologist, and I’m a cyborg.

I’m fascinated with cyborgs. Thinking about how humans throughout history, and maybe even before that, have been so intertwined with technology and have thus been cyborgs really tickles my brain. And so I’ve been asking people, “What’s your cyborg story?”

A faculty member at my university had knee surgery and mentioned that his new knee was an upgrade from his old one and how, sooner or later, he was going to get the other knee upgraded, too. What a way to talk about knee surgery.

In so many ways, our lives are mediated by our relationship with technology. When we think about a cyborg, we often picture a scene from a science fiction future. But being surrounded by all this technology, it’s easy to forget how strange and intertwined we are already with these systems. So in many ways, we are already cyborgs. So when did our cyborg relationship begin? And ultimately, who was the first cyborg?

Hi, Eshe.

Eshe: Hi, Cindy. Who are you? Can you tell me about yourself and your research?

Cindy: So I’m Cindy. I’m a prehistoric archaeologist. I’m a Ph.D. candidate at Arizona State University. Officially, my research interests are around stone tool technology: how it might have shaped and been shaped by people and their relationships with the environment and with each other. But unofficially, I’m a cyborg enthusiast.

Eshe: OK. What does that mean? Cyborg enthusiast?

Cindy: So that sounds really kind of wild and wacky. It sounds like I really love science fiction, and I do, but a cyborg enthusiast, for me, goes beyond that. So let me ask you, “What do you think of when you hear the word ‘cyborg’?”

Eshe: I feel like the word “cyborg” conjures up an image. It’s some sort of human form with a lot of metallic parts, kind of like a robot. But maybe there’s some skin showing on certain parts.

Cindy: It’s really interesting to hear how different people answer this question. So I think it’s useful to trace where this comes from in terms of where the word “cyborg” come from, so that we can think about why we have certain associations with it today. So the origin of the term “cyborg” comes from a paper in the 1960s. It was titled “Cyborgs and Space.” This was by Manfred Clynes and Nathan Kline.

And maybe you can guess. It’s about humans in space. In this paper, they introduce the term “cyborg,” and they introduce it as short for “cybernetic organism.” So a system, they call it, with organic and inorganic parts. They basically propose that, instead of altering space to suit humans, they think that we should alter humans, so that we can cope better with the challenges of space. In their words, they say, “Why not engineer humans to fit the stars?”

Eshe: It definitely sounds science fictiony, for sure.

Cindy: So it starts out in the realm of space travel, which definitely is science fictiony, right? But then, importantly for me, in 1984, Donna Haraway, who is a philosopher of science and a feminist studies scholar, writes A Cyborg Manifesto. And it takes this concept of the cyborg from space travel and this original starting point, and it does a deep dive into the philosophical and sociological impacts of the concepts of cyborgs. So it kicks off this movement—cyborg anthropology—and it’s outlined as the study of how we can define humanness in relationship to machines. And so, really, it’s about how science and technology can shape, and in return be shaped by, culture.

Eshe: OK. I’m following. How did you first encounter this concept?

Cindy: So this is really fun. Actually, what happened was I took this really great class early on in graduate school, and I had a professor who brought it up to us. He was a Type 1 diabetic, and he had an insulin pump that basically kept him alive. And in this discussion about cyborgs, he showed us his insulin pump and was like, “Look at this. I am a cyborg.” And this totally changed my perspective on cyborgs. I had a similar original image of these partly metal, partly flesh beings traveling [through] space, maybe. But I met my professor, who was this man with an insulin pump and who was a cyborg. And then I started reading more and more into cyborg anthropology, and it really began to open my eyes to all the ways that I am inseparable from technology and the ways that we all are.

Eshe: That explanation feels a bit more familiar; maybe a bit more familiar, more close, to me in a way. I still feel that skepticism. But I’m more intrigued.

Cindy: I feel like given everything that is going on in the world today, I think it’s pretty natural to feel skeptical about a really futuristic term like “cyborg.” So I think that’s a normal reaction. But stay with me here because there’s a really interesting journey that we can go on.

There was a book about 20 years ago by Andy Clark. It was titled Natural-Born Cyborgs: Minds, Technology, and the Future of Human Intelligence. And reading this book was really something that got me to think even more about cyborg-ness in my day-to-day life. Clark looked at trends in human technology and basically concluded that to be a cyborg is to be a human.

And then this book does this deeper dive into this idea that these technologies are embedded in life and transforming life. The thesis of his book really comes down to the fact that, even before we had all of these kinds of new cyborg technologies, humans have always been inseparable from technology.

Eshe: OK. So it sounds to me like you’re saying that humans have always been cyborgs. In which case, I wonder what the point of this argument is; if this is just the way we are as human beings, if we’ve historically also had this intertwined relationship with what we would now call technology, then what is the impact of this realization or discovery? Why is this a big deal if this is just kind of the way that we’ve always been?

Cindy: That’s a great point. And that’s something that I spent a lot of time thinking about, too—other than the fact that it’s cool to call myself a cyborg all the time. At the core of this discussion, for me, is this really interesting feedback loop that we and the technologies that we invent have.

So in the book, Clark talks about time and the clock as a nonpenetrative cyborg technology and something that’s really shaped human existence. So if you really think about it, our bodies don’t naturally have a sense of how long a second or a minute or an hour are. We don’t have bodies that are built for eight-hour workdays, eight hours of sleep, designated meal times, or anything like that. These things occur because we invented measurements of time and the tools to keep the time. And then our bodies became shaped to this rhythm because of this technology we invented. And then we invent more things to help keep time.

Eshe: OK. So the argument is basically that we’re already surrounded by technology that influenced our lives, and that creates this kind of feedback loop.

Cindy: Yeah, yeah. It’s about integrating and reproducing and this loop. But for me, as an archaeologist, this idea that we are already cyborgs because of all the ways we are, and have been, intertwined with technologies has really stuck with me because of my interest in the deep past.

Eshe: OK. So where are you thinking of taking this now?

Cindy: I think the combination of me being a prehistoric archaeologist and a cyborg enthusiast has hand-in-hand led me to take you on this journey with me. We’re going to embark on this quest; this quest in search of the first cyborg.

Eshe: OK. Let’s do it.

[music]

Cindy: To aid in our search and as the first stop of our quest, I talked to one of my colleagues at the School of Human Evolution and Social Change, or SHESC for short.

Rob Boyd: My name’s Rob Boyd. I’m on the faculty at SHESC ASU, and I study cultural evolution, technology, and cooperation.

Cindy: Rob is a cornerstone in the study of cultural evolution and the evolution of technology. He’s also a connoisseur of interesting shirts and has the voice of a wizard. Rob’s work has really changed the way I think about technology and my relationship with it.

Rob: Everything we do is wrapped up in in various kinds of technology.

Cindy: One of the key changes was in what I thought about as technology.

Rob: So I think of technology as a kind of continuum. So think of a technology like a spear. It’s a thing. You hold it in your hand. You manufacture it. Everybody would agree that’s technology.

Cindy: But there are other modes of technology that Rob thinks about as well.

Rob: Now think about something like manioc process. So many varieties of manioc contain a cyanide-generating compound. And if you eat that too much, you suffer serious health problems, and eventually it kills you. I think of that as technology as well: the knowledge about how to extract the cyanide. It involves grinding and shredding and washing and a bunch of other things. There’s no tool. But the knowledge about how to do that is still technology. And, in fact, it’s a crucial part of adaptation for almost all people living on a plant-roots diet.

Cindy: Rob has a huge wealth of knowledge about cultural practices and technologies from all over the world. And so when I thought about my quest to find the first cyborg, Rob was someone who I figured could help initiate the journey. But he had some practical concerns.

Rob: So I’m not sure I know what a cyborg is. Is it an enhanced human or is it a robot?

Cindy: Once I explained that my concept of the cyborg was about externalizing our knowledge and cognition, and my hunt for the first cyborg was really about exploring how we and our technologies are interconnected, he understood that pretty well.

Rob: So think about an atlatl.

Cindy: An atlatl is a spear-thrower that uses leverage to allow its users to launch projectiles super fast.

Rob: An atlatl basically makes your arms longer. And so it’s like RoboCop, except not quite so fancy.

Cindy: And there were certainly other examples of technologies that humans invented, and then these technologies turned around and changed humans in return.

Rob: So writing had a huge effect on thinking, no doubt about it. Einstein said, “My pencil is much smarter than I am” because he couldn’t do those calculations in his head. He needed to write down the intermediate steps.

Cindy: Once we establish what a cyborg is, I ask him the core question that I really wanted to know: Who was the first cyborg, and when did our strange, intertwined relationship with technology begin?

Rob: I actually think, and this may not be the answer you’re looking for, but I think it goes before humans. So I would count shelters as technology. Birds depend completely on bird-constructed shelters. Creatures like beavers do all kinds of hydrologic engineering. And chimps, of course, and other primates make use of stones and sticks and various things.

Cindy: This wasn’t not the answer I was looking for, but it certainly threw a wrench into things. If we think about cyborgs as this interaction between the self and the technological systems and the ways that the technological systems make things possible that weren’t possible before, then maybe we are surrounded by cyborgs.

[break with a SAPIENS ad]

Cindy: Eshe, I’m having a crisis.

Eshe: All right. Deep breaths. What’s going on?

Cindy: I am having a cyborg crisis. So after talking to Rob, I realized that, actually, the way that I’ve been thinking about cyborgs ends up encompassing all these different animals: nonhuman cyborgs.

Eshe: I mean, I can’t say I’m surprised, right? I think the biggest issue for me here is human exceptionalism, where we love to forget that we’re animals or pretend that we’re not. And therefore, we think that the things that we do are magically different or just exponentially better than any other animal. And we’re just so busy being greater than everyone else that when we realize that other animals are doing the same thing, it just really throws us for a loop, right?

Cindy: Yeah, that’s totally fair. I’m just thinking about now all the cute videos that you see of, like, capuchin monkeys cracking their little rocks. And I’m just thinking about the capuchin cyborg or the chimpanzee termite-fishing; the literal stick that they use when they termite-fish. I guess that is the chimpanzee cyborg.

Eshe: And elephants use sticks to scratch their backs or swat flies. And there’s gulls that have been seen using bread to bait fish. I find this less of an upsetting realization than thinking about human cyborgs in that sciency sense. I don’t know why, but this is comforting. Oh, everyone uses tools. That’s cool.

Cindy: Yeah, I guess it is. It is really incredible that everyone uses tools. Everyone figures out their environment in some way, right?

But coming back to our original quest and really thinking about it, and all of the examples of nonhuman animal tool use is really fascinating. But there is still something that is undeniably unique about the human relationship with technology. You and I are talking to each other right now via the Internet, via our computers. That is this whole thing that humans managed to invent and set up and connect people in ways that are so futuristic.

Eshe: I think it’s fair to look at the diversity within the use of tools. And I think it’s fair and expected that as anthropologists, we are focused on the human experience.

Cindy: That’s a good way of putting it. Maybe me and my distress have derailed us in this journey for the first cyborg because I’ve been having to reconceptualize the cyborg. I think the question that I’m trying to answer is no longer “Who was the first cyborg?” But rather more like, “What is the origin point of our cyborg journey or our journey with technology?”

Eshe: That feels like a different question. I think it’s related to this idea of being a cyborg. It makes sense to me. I’m ready for more.

Cindy: Great. OK. So when I did talk to Rob, he did bring up a really great point about the specific thing that humans do with technology.

Rob: What make humans different is that our technology, at least in some contexts, gets gradually better over time. And so that allows us to generate much fancier, much more complex, and much more habitat-specific technology. So the Inuit would have one set of technologies and the Aché [would have] a different set of technologies, and they’re both well designed for their circumstances. As far as I know, there’s no other animal that does that. The fact that we cumulatively evolve technology means that the feedback loop can keep going on and on and on.

Cindy: So we could begin with things as simple as stone tools and end up with super-specialized technologies that thrive in tough environments, like the Inuit or the Aché, or in a different path where we end up building giant cities that rely on layers and layers of infrastructure and technology.

Rob: And after a while, you end up with Los Angeles!

Cindy: So the human cyborg has the ability to accumulate and improve on the technology. So this origin of this ability is the more specific question in the hunt for the first cyborg. When did we start to accumulate technology or accumulate the knowledge to improve upon it?

Eshe: OK. That sounds super interesting to me.

Cindy: To answer this question, I think I need another wizard, and luckily I know just the person to consult. So the next stop in our quest is to speak to a fellow archaeologist and someone who has the same cyborg fascination as me.

Jonathan Page: I have a lot of thoughts on cyborgs. It’s kind of interesting because I feel like in popular culture, people show cyborgs as these weird, almost deviant things that are kind of gross.

Cindy: This is my friend and colleague Jonathan Page. He’s a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Missouri. He studies technological change and how that relates to the hominin lineage.

Jonathan: You know, I think of Darth Vader … He’s a guy. He almost dies. And they turn him into a cyborg. And now he’s this terrible creature, almost. So I think a cyborg has this scary component to it. But we’re all just so entrenched in technology that we all have this kind of aspect to it. And you don’t have to put this in, but I’ve been playing Metal Gear Solid a lot.

Cindy: Metal Gear Solid is a video game series where you play as the protagonist Solid Snake, who is a genetically modified super soldier; one of his allies, Gray Fox, is another super soldier but with a machine exoskeleton. So clearly, Jon is in the perfect headspace for our conversation. But he had some insights about what was unique about the human cyborg.

Jonathan: It’s not just that “Oh, we rely on technology,” but we evolved in a niche that is purely technological, and that’s separate from a lot of other animals that use technology.

Cindy: I asked him about Rob’s point about accumulation, about how the uniquely human thing might be the gradual improvement of our technologies through time. It’s something that Jon has spent a lot of time thinking about.

Jonathan: So with accumulation, I think of how hominins made technologies as these little recipes. They’re just these little recipes that hominins are coming up with and passing down and modifying and things like that. And at least for a lot of hominin evolution, it seems like there’s not a ton of accumulation going on. There’s some happening, but even chimpanzees and other animals can make technologies that have a certain number of steps involved in them. Like, termite probes have a production sequence, so it’s complex to a degree. But I got really interested in trying to figure out when in hominin evolution we start to see recipes that are unusually long.

Cindy: An easy way to think about this is by imagining that you’re given a goal—like, trying to fish some termites out of their mound and eating them—and a set of materials, say, some branches or leaves and things from the forest. Now how hard would it be for you to figure out that you can use the sticks to get the termites out of the mound? It might take you a bit, but I think eventually you’d figure out that you can take a branch, fashion it into a tool of some sort, and dip it into the mound to get at the termites. This is what Jon would refer to as a simple recipe. The steps involved are not too complicated, and this relatively simple recipe is what was happening through a lot of hominin evolution.

Now imagine your goal is to hunt an animal; a deer, for example. And for this, you’re also given some materials from the forest—some rocks, some branches, and maybe some bark. Now how hard would it be for you to figure out how to make a spear to hunt with? First, you’d have to figure out how to make a stone tool from the rocks to use that to cut and shape the wood into a shaft, make a stone point, make some sort of glue, and then finally take that point and glue it onto your wooden shaft to make that spear. And even if you break it down step by step, it still seems like it might be pretty difficult for most people. And this is what Jon would refer to as a long recipe. And our hominin ancestors did figure out each of these steps at some point.

Based on his research, Jon had an idea of when these recipes started getting unusually long.

Jonathan: So that kind of time period of when that seems to happen, at least in my data set, is in the middle Pleistocene (in the paper we’ve been working on, where we measure the complexity of these toolmaking sequences and compare them to chimpanzees and other things). That finding suggests that by about 800,000 years ago, you have hominins who are relying on these complex technologies.

Cindy: And these complex technologies can be seen as evidence for the turning point of the hominin relationship with technology.

Jonathan: So by after about 800,000 years ago, you have hominins who are making tools like Levallois technologies that have a lot of actions that are in sequence.

Cindy: Levallois technologies are a type of stone tool technology that requires a lot of preplanning. Many researchers view the emergence of these tools as a major change in the stone tool record compared to the relatively simpler tools that came before.

Jonathan: And that’s also a time when you have all these other kinds of interesting things that are happening. You have the earliest cases of hafting, which is arguably an even better example of accumulative culture because you have a combination of these. So you have a stone point, and you have some glue, and you have a sinew or something like that. You have a lot of different technologies that are coming together and being combined into something that hominins were now relying on. This is also when hominins really start relying on fire a lot. So there’s just a lot of things that are happening in the middle Pleistocene, after about 800,000 years ago, that suggests that these hominins are accumulating a lot of different things.

Cindy: When I asked him what hominin species he thought would have been the first cyborg, he had two different answers for me.

Jonathan: I feel like I want it to be Homo erectus [laughs], even though our findings are “Well, it’s later on; it’s the middle Pleistocene when we’re for sure it existed.” But I’d be very happy to extend that farther back in time. But it’s a different world because we don’t know how they are passing on culture. Is it their language? Or are they teaching it? There’s a whole bunch of things that we don’t know. But I do kind of want to extend it to Homo erectus, at least.

You can at least say that all Homo sapiens and whatever other kind of middle Pleistocene hominins were running around were for sure cyborgs. But when it went from not cyborg to cyborg, it was a gradual thing. It depends on what your threshold is.

Cindy: So here we are. The first cyborg was probably not a human being as we know ourselves but rather some hominin ancestor 800,000 years ago or more. And the process of becoming cyborgs was slow and gradual.

[music]

Eshe: We went on quite a journey to find the first cyborg. Where are we now?

Cindy: Yeah, I think it’s really interesting. When we first started this quest, I thought I had a really clear, really defined idea of what I thought a cyborg was. It was all about technology and how we’re so intertwined with it. And so from that perspective, the search for the first cyborg seemed super straightforward. And now the framework was definitely naive, right? But it was also fun and really exciting.

Eshe: Yeah, I’m right there with you. I think it’s pretty incredible, too.

Cindy: So we made it, right? I guess we completed the quest we set out in the beginning.

Eshe: We did it.

Cindy: We went on a side quest about nonhuman animals. But ultimately, I think we came to an answer and a pretty nice conclusion.

Eshe: I think so, too. This is great. Thanks, Cindy.

Cindy: Thanks for coming along.

[music]

Eshe: SAPIENS is produced by House of Pod. Cat Jaffee and Dennis Funk are our producers and program teachers. Dennis is also our audio editor and sound designer. Christine Weeber is our copy editor. Our executive producers are Cat Jaffee and Chip Colwell. This episode is part of the SAPIENS Public Scholars Training Fellowship program, which provides in-depth training for anthropologists in the craft of science communication and public scholarship.

SAPIENS is an editorially independent podcast funded this season by the John Templeton Foundation with the support of the University of Chicago Press and the Wenner-Gren Foundation. SAPIENS is part of the American Anthropological Association Podcast Library. Please visit SAPIENS.org to check out the additional resources in the show notes and to see all our great stories about everything human. I’m Eshe Lewis. Thank you for listening.