Finding Ceremony for Ancestors Held in the Penn Museum and Other Colonial Institutions

On February 13, 2023, a Pennsylvania court decided the fate of cranial remains from 20 Black Philadelphians that have been kept in the basement of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

The court granted Penn Museum’s request to bury the remains—without requiring the university to identify the deceased and notify their descendants. According to the judge’s decree, resulting from this unprecedented court process, the burial must occur by February 13, 2024.

Some of these individuals may have been enslaved during their lifetimes. We witness in this process that the Ivy League university has turned them into property once again, referring to their bones as “charitable assets” during a status conference one week before the hearing.

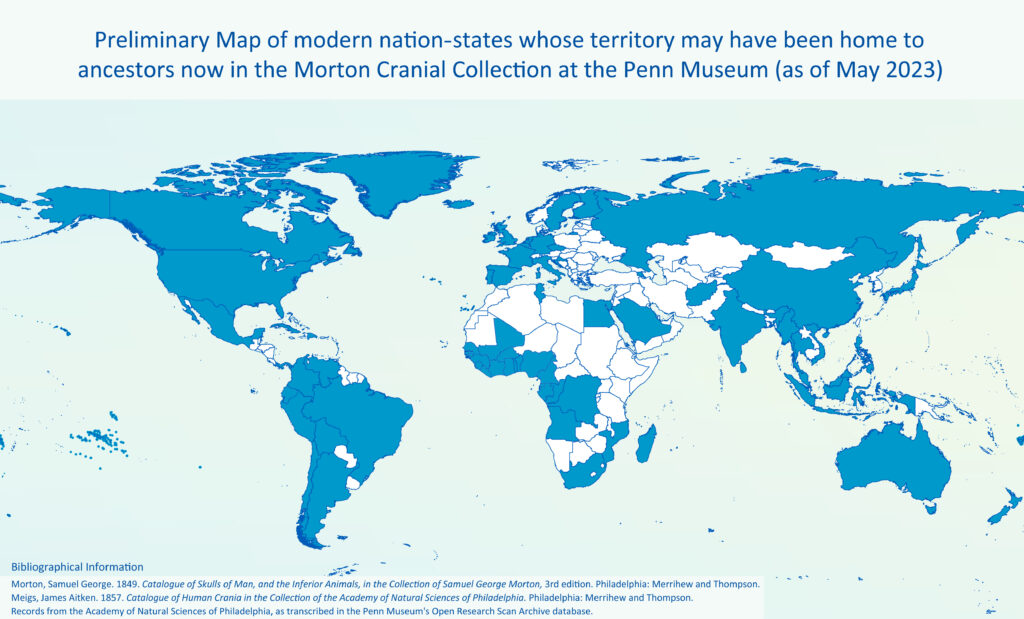

The 20 crania that Penn seeks to bury are part of the Penn Museum’s Morton Cranial Collection, which contains the cranial remains of between 1,300 and 1,600 people. The majority were collected in the 1830s and 1840s by Penn alum Dr. Samuel George Morton, one of the founders of physical anthropology.

For generations, Penn has exerted control over these and other ancestors’ remains through theft, display, and research-based extraction. We seek a consent-based process controlled by descendants and descendant community members, a process we call “Finding Ceremony.”

While “craniologists” like Morton were largely concerned with amassing and measuring “racial types” from around the world, they also plundered the disenfranchised dead of their own cities. Morton amassed his collection from home and abroad. Both practices were, ultimately, about collecting trophies of heteropatriarchal white supremacy.

The trafficking of remains belonging to other people’s ancestors dominated Morton’s correspondence. On February 3, 1837, Bostonian Dr. John Collins Warren, an early leader in surgical education in the United States and the first dean of Harvard’s Medical School, wrote to his Philadelphia colleague, Morton, asking, “Have you the Guanche? If not, I can let you have a head.” A couple months later, Warren sent Morton the “head,” along with a brief anecdote about how his friend found and stole it for him.

Today that skull of an Indigenous person from the Canary Islands, Dr. Warren’s gift to Dr. Morton, sits on a wooden shelf in an old cabinet in the basement of the Penn Museum. On those same shelves, in those same cabinets, sit crania of people from other parts of the world.

Morton made casts of some of those skulls and sent them to Warren in 1849. Today four of Morton’s plaster replicas of stolen heads—representing what he claimed to be “typical” German, Graeco-Egyptian, ancient Egyptian, and Malay skulls—are part of the Warren Anatomical Museum at Harvard University.

Warren and Morton are just two examples of the depraved history of trafficking in the skulls of our ancestors as part of the larger racial science project of the European Enlightenment to “prove” the superiority of the white race. This laid the groundwork for the way that race operates in the present.

Today Harvard and Penn are faced with the material legacy of the racist collections of Warren, Morton, and others, and they are going about it in very different ways.

Juxtapose Harvard’s September 2022 report examining its racist collections of human remains to Penn’s May 2022 request for legal authorization to bury the Black Philadelphians. Harvard’s report foregrounds the need to perform archival research on each possibly enslaved individual and to identify their descendants before taking further steps. Beyond that, they recognize descendant communities as a valid stewardship entity.

Penn’s legal request, on the other hand, continues to rush a process without legitimate community input. The Morton Cranial Collection Community Advisory Group, which Penn claims recommended that this burial take place, was not organized by descendant community members, but was instead formed by Penn Museum’s director, Christopher Woods. This advisory group has no control of decisions about the stewardship of the remains in this collection, and were given a proposal from the museum director, without having time to deliberate as a body or fully understand what the collection is. Despite being called a “community” group, five out of its 14 members are high-level Penn administrators. Worse, their meeting minutes do not indicate anywhere that the group made the recommendation to bury the crania.

Penn has also failed to perform the archival research that Harvard identifies as necessary in their own report. In their original petition to the court, Penn stated: “Only one of the thirteen crania has been identified, as John Vorhees (sic), for whom no descendants have been traced.” It has become clear to us in subsequent conversations, and during the hearing itself, that the museum has done no research into the identity of those they wish to bury and argues that no research can be done.

Additionally, in their Research Report released in January 2023, it is evident that the Penn Museum did not consult any of the abundant archival material held by governmental, institutional, and private repositories in and around Philadelphia. In their disrespectful negligence, the museum deploys a long-standing racist tool of denying the recorded pasts of marginalized people in the United States. In just a few hours of archival research in the city of Philadelphia’s archival collections from the almshouse where many of the individuals Penn wishes to bury died, one of the authors has already been able to locate key information about them; we are now working to identify their descendants—work that was Penn’s responsibility to do, long before asking a judge for permission to bury them.

In response to the historical subjugation and desecration of ancestral remains by museums and universities, we proposed to the court a descendant community-controlled process called Finding Ceremony.

When we say, “finding ceremony,” we mean restoring the lineages of care, reverence, and spiritual memory to the work of caring for our dead. We understand, as two members of different descendant communities reflected in human collections at Penn, Harvard, and elsewhere, that the colonial violence that situated our ancestors as collected and collective crania means that our work is tied together.

We undertake the work knowing that we won’t fully contend with the harm enacted on these individuals over centuries. Generations of their descendants, who might have remembered and honored them, have lived and died. This is due to the rupture caused by empire built on justifications ground out of our bones, based on racialized science.

Finding Ceremony will offer a space of transition, where our ancestors go from being defined as specimens in a scientific, museum “collection” and move toward ceremony and rest. The first, essential step in this process is to remove the crania from the Penn Museum—a spatial transfer and a spiritual shift. We will welcome the over 1,300 crania currently in the Morton Cranial Collection through the Finding Ceremony Uncollection.

These ancestors will be intentionally honored, cared for, and understood by connecting them with descendants and relatives who can give them rest. We have begun the work of archival research to identify the 20 Black Philadelphians who Penn plans to bury, to locate and notify their descendants prior to their burial by Penn, and to convene descendant community members who are concerned with the care of ancestors who may not have known descendants.

Ultimately, Finding Ceremony is a reparationist project: This work must be funded by the same institutions that have perpetrated the harm over centuries and that have demonstrated an unwillingness to do the labor that we now take on.

In the coming period, we will be hosting public meetings, starting in Philadelphia, to gather descendant communities and inform them about what we know.

West Philadelphia is a historically Black community that has already been targeted repeatedly by the university and the museum through decades-long displacement and through two revelations in 2021 that their ancestors’ and relatives’ remains had been held in the Penn Museum.

The presence of Black Philadelphians in the Morton Cranial Collection—the same individuals who Penn now seeks to bury—was surfaced by a report written by a Penn graduate student in February 2021. In late April 2021, one of the authors reported that the remains of Black children who were their neighbors, who were murdered in the 1985 MOVE bombing, were sitting in a box in the same museum basement. These remains were used as teaching material for an online course.

In the aftermath of these revelations, the museum characterized its actions as doing the right thing, but in reality, the institution continued the pattern of paternalistic colonial arrogance by making decisions for other people’s ancestors.

Finding Ceremony will be reconvening a community that gathered to honor these ancestors in April 2021. We will address the horrifying reality of ongoing abuse by the Penn Museum, an institution that continues to exploit ancestors’ remains and disregard the wishes of descendant community members.

Editors’ Note: This essay is an updated version of one the authors wrote in January 2023.