How Human Are We?

This article was originally published at The Conversation and has been republished under Creative Commons.

READER QUESTION: We now know from evolutionary science that humanity has existed in some form or another for around two million years or more. Homo sapiens are comparatively new on the block. There were also many other human species, some that we interbred with. The question is then inevitable: When can we claim personhood in the long story of evolution? Are chimpanzees people? Did Australopithecine have an afterlife? What are the implications for how we think about rights and religion? Anthony A. MacIsaac, 26, Paris, France

In our mythologies, there’s often a singular moment when we became “human.” Eve plucked the fruit of the tree of knowledge and gained awareness of good and evil. Prometheus created men from clay and gave them fire. But in the modern origin story, evolution, there’s no defining moment of creation. Instead, humans emerged gradually, generation by generation, from earlier species.

As with any other complex adaptation—a bird’s wing, a whale’s fluke, our own fingers—our humanity evolved step by step, over millions of years. Mutations appeared in our DNA, spread through the population, and our ancestors slowly became something more like us and, finally, we appeared.

STRANGE APES, BUT STILL APES

People are animals, but we’re unlike other animals. We have complex languages that let us articulate and communicate ideas. We’re creative: We make art, music, tools. Our imaginations let us think up worlds that once existed, dream up worlds that might yet exist, and reorder the external world according to those thoughts. Our social lives are complex networks of families, friends, and tribes, linked by a sense of responsibility toward one another. We also have awareness of ourselves and our universe: sentience, sapience, consciousness, whatever you call it.

And yet the distinction between us and other animals is, arguably, artificial. Animals are more like humans than we might think—or like to think. Almost all behaviors we once considered unique to ourselves are seen in animals, even if they’re less well-developed.

That’s especially true of the great apes. Chimps, for example, have simple gestural and verbal communication. They make crude tools, even weapons, and different groups have different suites of tools—distinct cultures. Chimps also have complex social lives and cooperate with one another.

As Darwin noted in The Descent of Man, almost everything odd about Homo sapiens—emotion, cognition, language, tools, society—exists, in some primitive form, in other animals. We’re different, but less different than we think.

And in the past, some species were far more like us than other apes—Ardipithecus, Australopithecus, Homo erectus, and Neanderthals. H. sapiens is the only survivor of a once diverse group of humans and human-like apes, the hominins, which includes around 20 known species and probably dozens of unknown species.

The extinction of those other hominins wiped out all the species that were intermediate between us and other apes, creating the impression that some vast, unbridgeable gulf separates us from the rest of life on Earth. But the division would be far less clear if those species still existed. What looks like a bright, sharp dividing line is really an artifact of extinction.

The discovery of these extinct species now blurs that line again and shows how the distance between us and other animals was crossed—gradually, over millennia.

THE EVOLUTION OF HUMANITY

Our lineage probably split from the chimpanzees around 6 million years ago. These first hominins, members of the human line, would barely have seemed human, however. For the first few million years, hominin evolution was slow.

The first big change was walking upright, which let hominins move away from forests into more open grassland and bush. But if they walked like us, nothing else suggests the first hominins were any more human than chimps or gorillas. Ardipithecus, the earliest well-known hominin, had a brain that was slightly smaller than a chimp’s, and there’s no evidence they used tools.

In the next million years, Australopithecus appeared. Australopithecus had a slightly larger brain—larger than a chimp’s, still smaller than a gorilla’s. It made slightly more sophisticated tools than chimps, using sharp stones to butcher animals.

Then came Homo habilis. For the first time, hominin brain size exceeded that of other apes. Tools—stone flakes, hammer stones, “choppers”—became much more complex. After that, around 2 million years ago, human evolution accelerated, for reasons we’ve yet to understand.

BIG BRAINS

At this point, H. erectus appeared. Erectus was taller, was more like us in stature, and had large brains—several times bigger than a chimp’s brain, and up to two-thirds the size of ours. They made sophisticated tools, such as stone hand axes. This was a major technological advance. Hand axes needed skill and planning to create, and you probably had to be taught how to make one. It may have been a meta-tool—used to fashion other tools, such as spears and digging sticks.

Like us, H. erectus had small teeth. That suggests a shift from plant-based diets to eating more meat, probably from hunting.

It’s here that our evolution seems to accelerate. The big-brained erectus soon gave rise to even larger-brained species. These highly intelligent hominins spread through Africa and Eurasia, evolving into Neanderthals, Denisovans, Homo rhodesiensis, and archaic H. sapiens. Technology became far more advanced—stone-tipped spears and fire-making appeared. Objects with no clear functionality, such as jewelry and art, also showed up over the past half million years.

Some of these species were startlingly like us in their skeletons, and their DNA.

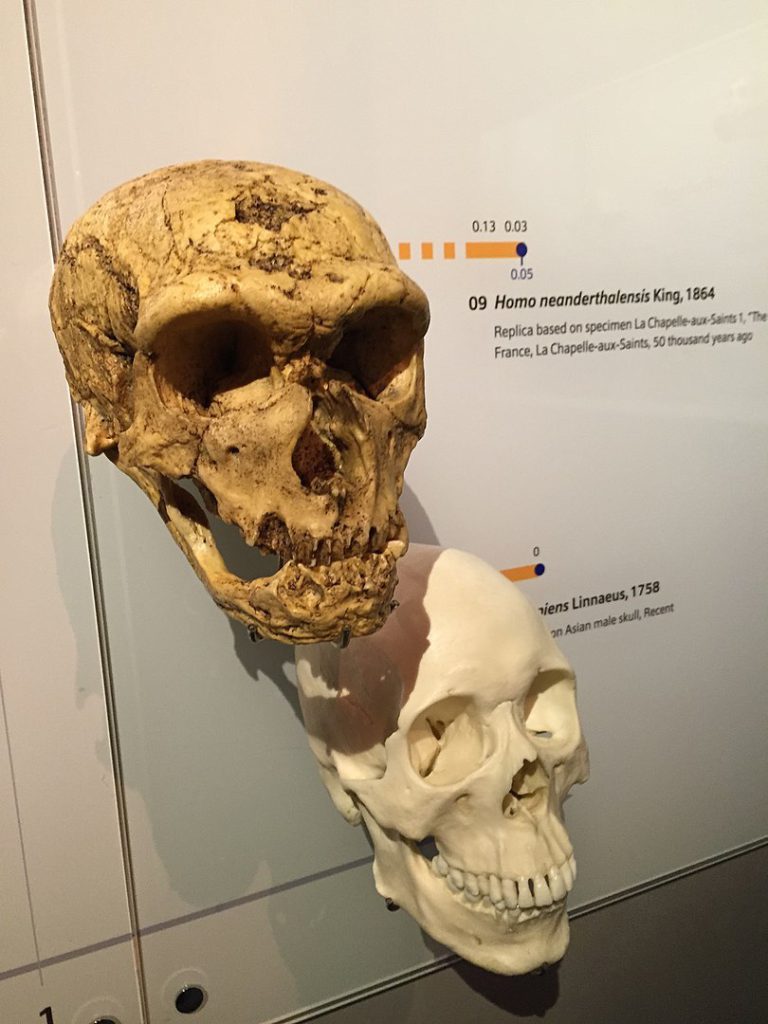

Homo neanderthalensis, the Neanderthals, had brains approaching ours in size and evolved even larger brains over time until the last Neanderthals had cranial capacities comparable to a modern human’s. They might have thought of themselves, even spoken of themselves, as human.

The Neanderthal archaeological record records uniquely human behavior, suggesting a mind resembling ours. Neanderthals were skilled, versatile hunters, exploiting everything from rabbits to rhinoceroses and woolly mammoths. They made sophisticated tools, such as throwing spears tipped with stone points. They fashioned jewelry from shells, animal teeth, and eagle talons, and made cave art. And Neanderthal ears were, like ours, adapted to hear the subtleties of speech. We know they buried their dead and probably mourned them.

There’s so much about Neanderthals we don’t know, and never will. But if they were so like us in their skeletons and their behavior, it’s reasonable to guess they may have been like us in other ways that don’t leave a record—that they sang and danced, that they feared spirits and worshipped gods, that they wondered at the stars, told stories, laughed with friends, and loved their children. To the extent Neanderthals were like us, they must have been capable of acts of great kindness and empathy, but also cruelty, violence, and deceit.

Far less is known about other species, like Denisovans, H. rhodesiensis, and extinct sapiens, but it’s reasonable to guess from their large brains and human-looking skulls that they were also very much like us.

LOVE AND WAR

I admit this sounds speculative but for one detail. The DNA of Neanderthals, Denisovans, and other hominins is found in us. We met them, and we had children together. That says a lot about how human they were.

It’s not impossible that H. sapiens took Neanderthal women captive, or vice versa. But for Neanderthal genes to enter our populations, we had to not only mate but successfully raise children, who grew up to raise children of their own. That’s more likely to happen if these pairings resulted from voluntary intermarriage. Mixing of genes also required their hybrid descendants to become accepted into their groups—to be treated as fully human.

Learn more, from the archives: “Five Human Species You May Not Know About“

These arguments hold not only for the Neanderthals, I’d argue, but for other species we interbred with, including Denisovans, and unknown hominins in Africa. Which isn’t to say that encounters between our species were without prejudice or entirely peaceful. We were probably responsible for the extinction of these species. But there must have been times we looked past our differences to find a shared humanity.

Finally, it’s telling that while we did replace these other hominins, this took time. Extinction of Neanderthals, Denisovans, and other species took hundreds of thousands of years. If Neanderthals and Denisovans were really just stupid, grunting brutes, lacking language or complex thought, it’s impossible they could have held modern humans off as long as they did.

THE HUMAN EDGE

Why, if they were so like us, did we replace them? It’s unclear, which suggests the difference was something that doesn’t leave clear marks in fossils or stone tools. Perhaps a spark of creativity—a way with words, a knack for tools, social skills—gave us an edge. Whatever the difference was, it was subtle, or it wouldn’t have taken us so long to win out.

While we don’t know exactly what these differences were, our distinctive skull shape may offer a clue. Neanderthals had elongated crania, with massive brow ridges. Humans have a bulbous skull, shaped like a soccer ball, and lack brow

Why, if they were so like us, did we replace them?

ridges. Curiously, the peculiarly smooth, round head of adult H. sapiens is seen in young Neanderthals—and even baby apes. Similarly, juvenilized skulls of wild animals are found in domesticated ones, such as domestic dogs: An adult dog skull resembles the skull of a wolf pup. These similarities aren’t just superficial. Dogs are behaviorally like young wolves—[less aggressive] and more playful.

My suspicion, mostly a hunch, is that H. sapiens’ edge might not necessarily be raw intelligence but differences in attitude. Like dogs, we may retain juvenile behaviors, things like playfulness, openness to meeting new people, lower aggression, more creativity, and curiosity. This in turn might have helped us make our societies larger, more complex, collaborative, open, and innovative—which then outcompeted theirs.

BUT WHAT IS IT?

Until now, I’ve dodged an important question, arguably the most important one. It’s all well and good to discuss how our humanity evolved—but what even is humanity? How can we study and recognize it, without defining it?

People tend to assume there’s something that makes us fundamentally different from other animals. Most people, for example, would tend to think that it’s OK to sell, cook, or eat a cow, but not to do the same to the butcher. This would be, well, inhuman. As a society, we tolerate displaying chimps and gorillas in cages but would be uncomfortable doing this to one another. Similarly, we can go to a shop and buy a puppy or a kitten, but not a baby.

The rules are different for us and them. Even die-hard animal-rights activists advocate animal rights for animals, not human rights. No one is proposing giving apes the right to vote or stand for office. We inherently see ourselves as occupying a different moral and spiritual plane. We might bury our dead pet, but we wouldn’t expect the dog’s ghost to haunt us or to find the cat waiting in heaven.

And yet it’s hard to find evidence for this kind of fundamental difference.

The word humanity implies taking care of and having compassion for one another, but that’s arguably a mammalian quality, not a human one. A mother cat cares for her kittens, and a dog loves his or her master, perhaps more than any human does. Killer whales and elephants form lifelong family bonds. Orcas grieve for their dead calves, and elephants have been seen visiting the remains of their dead companions. Emotional lives and relationships aren’t unique to us.

Perhaps it’s awareness that sets us apart. But dogs and cats certainly seem aware of us—they recognize us as individuals, as we recognize them. They understand us well enough to know how to get us to give them food or let them out the door—or even when we’ve had a bad day and need company. If that’s not awareness, what is?

We might point to our large brains as setting us apart, but does that make us human? Bottlenose dolphins have somewhat larger brains than we do. Elephant brains are three times the size of ours; orcas, four times; and sperm whales, five times. Brain size also varies in humans. Albert Einstein had a relatively small brain—smaller than the average Neanderthal, Denisovan, or H. rhodesiensis—was he less human? Something other than brain size must make us human—or maybe there’s more going on in the minds of other animals, including extinct hominins, than we think.

We could define humanity in terms of higher cognitive abilities—art, math, music, language. This creates a curious problem because humans vary in how well we do all these things. I’m less mathematically inclined than Steven Hawking, less literary than Jane Austen, less inventive than Steve Jobs, less musical than Taylor Swift, less articulate than Martin Luther King Jr. In these respects, am I less human than they are or were?

If we can’t even define it, how can we really say where it starts and where it ends—or that we’re unique? Why do we insist on treating other species as inherently inferior if we’re not exactly sure what makes us, us?

Neither are we necessarily the logical endpoint of human evolution. We were one of many hominin species, and yes, we won out. But it’s possible to imagine another evolutionary course, a different sequence of mutations and historical events leading to Neanderthal archaeologists studying our strange, bubble-like skulls, wondering just how human we were.

The nature of evolution means that living things don’t fit into neat categories. Species gradually change from one into another, and every individual in a species is slightly different—that makes evolutionary change possible. But that makes defining humanity hard.

We’re both unlike other animals due to natural selection and like them because of shared ancestry: the same, yet different. And we humans are both like and unlike one another—united by common ancestry with other H. sapiens but different due to evolution and the unique combination of genes we inherit from our families or even other species, such as Neanderthals and Denisovans.

It’s hard to classify living things in strict categories because evolution constantly changes things, creating diverse species and diversity within species.

And what diversity it is.

True, in some ways, our species isn’t that diverse. H. sapiens shows less genetic diversity than your average bacterial strain; our bodies show less variation in shape than sponges or roses or oak trees. But in our behavior, humanity is wildly diverse. We are hunters, farmers, mathematicians, soldiers, explorers, carpenters, criminals, and artists. There are so many different ways of being human, so many different aspects to the human condition, and each of us has to define and discover what it means to be human. It is, ironically, this inability to define humanity that is one of our most human characteristics.