How Tourism Reinvented Jesus’ Baptism Site

On a scorching afternoon in July, dozens of people dressed in white gowns wait in line, slowly inching forward along the winding cement and stone path that leads down into the Jordan River, which is lined with eucalyptus and palm trees. One by one, these modern-day pilgrims wade into the clear waist-high water, where a Roman Catholic priest who is traveling with a group from Trinidad dunks each person under water three times. “I baptize you in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit,” the priest intones.

As Dianne Beptiste climbs back up the steps into the shaded amphitheater overlooking the river, her gown dripping with water, she is smiling. She uses a towel to squeeze water out of her hair and then picks up her bag, ready to head back to the changing room. “It was a feeling of being one with Jesus, being part of Jesus’ experience,” says Beptiste, who works as an accountant in Trinidad. She is on a 10-day tour of Israel and its Christian holy sites for what is her first visit to the country. Beptiste emphasizes that the immersion in the Jordan was a renewal of her original Catholic baptism at infancy. “It was really kind of emotional, the feeling of being in the place where Jesus was baptized,” Beptiste says.

But it was only recently, in 1981, that this spot on the Jordan, called the Yardenit Baptismal Site, became associated with Jesus’ baptism. Until then, it was simply part of Kibbutz Kinneret, a secular Jewish-Israeli farming collective on the banks of the upper Jordan River. (A kibbutz is a collective community, typically based on agriculture.) The farm is in northern Israel, just southwest of the Sea of Galilee and about 100 miles from Jerusalem. The traditional area of baptism for Christian pilgrims, dating back to at least the fourth century, is about 70 miles downstream, near where the Jordan River feeds into the Dead Sea.

But political conflict over the years resulted in much of the Jordan River being placed off-limits to visitors. The closing of the ancient baptismal area downstream, along with commercial marketing and a continued desire on the part of pilgrims to have a baptismal experience connecting them with Jesus, has propelled Yardenit to international prominence in recent decades. It is currently the most popular place for Jordan River baptisms—even with the recent reopening of the ancient site downstream—and it attracts more than half a million visitors each year, despite its lack of Christian pilgrimage history.

Yardenit offers little religious or historic authenticity, says Noam Savion, a licensed Israeli tour guide who is accompanying Beptiste’s group around the country. “But it is still a special experience,” Savion adds, as he waits for the group to finish their immersion in the river.

Given its relatively short history as a baptismal site, the popularity of Yardenit suggests that so-called “sacred places” may simply be where people find fulfillment and connection rather than where archaeologists and historians find evidence; sometimes past traditions and present practices overlap, but not always. A sacred “place” can indeed change location and character over time, or alternative sites can emerge, depending on the needs and desires of pilgrims and tourists.

Yardenit is a telling example of how political conflict and commercialism—along with historical and archaeological evidence—can play a role when it comes to places of religious pilgrimage, says Lior Chen, a doctoral candidate in anthropology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Chen is writing a dissertation based on field research examining the emergence of baptismal sites along the Jordan River. “It just shows how really it’s people who decide a place is holy, and it is people who imagine, establish, and construct sacred places,” he explains. Although Yardenit grew out of both convenience and entrepreneurship, “now, in the eyes of the tourism industry, [it] has become the ‘traditional’ place.”

The Jordan River has long attracted pilgrims, as all four Gospels in the New Testament refer to Jesus being baptized in this river by John the Baptist. Jesus’ baptism is widely considered by Christians to have been the beginning of his public life and ministry. Only the Gospel of John names the specific location on the river where his baptism occurred—“Bethabara [or Bethany in some translations] beyond Jordan.” Hard evidence has not been found to tie this biblical place name to any precise location along the river; however, the oldest known travelers’ accounts, dating to the fourth century, do describe the place revered for Jesus’ baptism as being 5 miles above where the river flows into the Dead Sea.

One account, “On the Topography of the Holy Land,” written by a pilgrim named Theodosius and dating from A.D. 530, describes a cross mounted on a pillar in the middle of the river, 5 miles north of the Dead Sea, marking the site of the baptism. A subsequent sixth-century account describes marble steps at this site that went down into the water from both banks. Archaeological remains of churches and monasteries dating to the fourth century have been found on both the east and west banks of the Jordan River in this area, offering evidence that the ancient site was already considered a holy place by just a few hundred years after Jesus, if not earlier.

It remained in use for centuries and eventually became quite popular with Christians in North America and Western Europe in the early 20th century, as the United States, England, France, and other countries grew interested in the Middle East and tours to the Holy Land became more common.

But the 1967 Six-Day War, launched by Israel after Egyptian troops mobilized to attack, brought strife to the region. The war soon drew in neighboring Syria and Jordan, and much of the Jordan River became a highly contested boundary between the country of Jordan and the new territories that the state of Israel had taken over during the fighting. Israel, Jordan, and the Palestinian Liberation Organization placed landmines on their respective riverbanks, cutting off access to the baptismal area. The churches and monasteries on both the Jordanian bank, surrounding a baptismal place known as Bethany Beyond the Jordan, and on the Israeli-controlled bank, around a baptismal site known as Qasr al-Yahud, were evacuated as the entire area became a closed military zone.

With the traditional baptismal sites inaccessible, Christian pilgrims to Israel began to visit the northern stretches of the river near the Sea of Galilee. Tourists and guides often parked their cars and buses on the side of a main highway and accessed the water on property belonging to various Jewish farming communities, including Kibbutz Kinneret.

Citing concerns about safety, the tourism ministry helped fund the establishment of an official site for baptisms in the river. Kibbutz Kinneret agreed to operate the site on its property, so Yardenit was born. “It basically started because it was a problem getting to Qasr al-Yahud,” explains Shahar Alon, a member of the Yardenit marketing team who lives in a nearby kibbutz. Yardenit began as a simple round building with a small parking lot, and a few kibbutz members worked to oversee it, creating a new stream of income for their community, old-timers there recall. “It was just a small place, very quiet, and not so busy at first,” says Tomoko Duger, who is a longtime member of the kibbutz.

Now Duger works at Yardenit’s massive gift shop, which employs 60 people and is a significant source of income for the kibbutz along with the snack bar and restaurant. The shop sells everything from local olive oil to rosaries to placemats depicting Jesus’ New Testament miracles. There is also a counter where visitors can buy or rent white gowns for baptism, rent towels, or purchase certificates stating that they underwent an immersion.

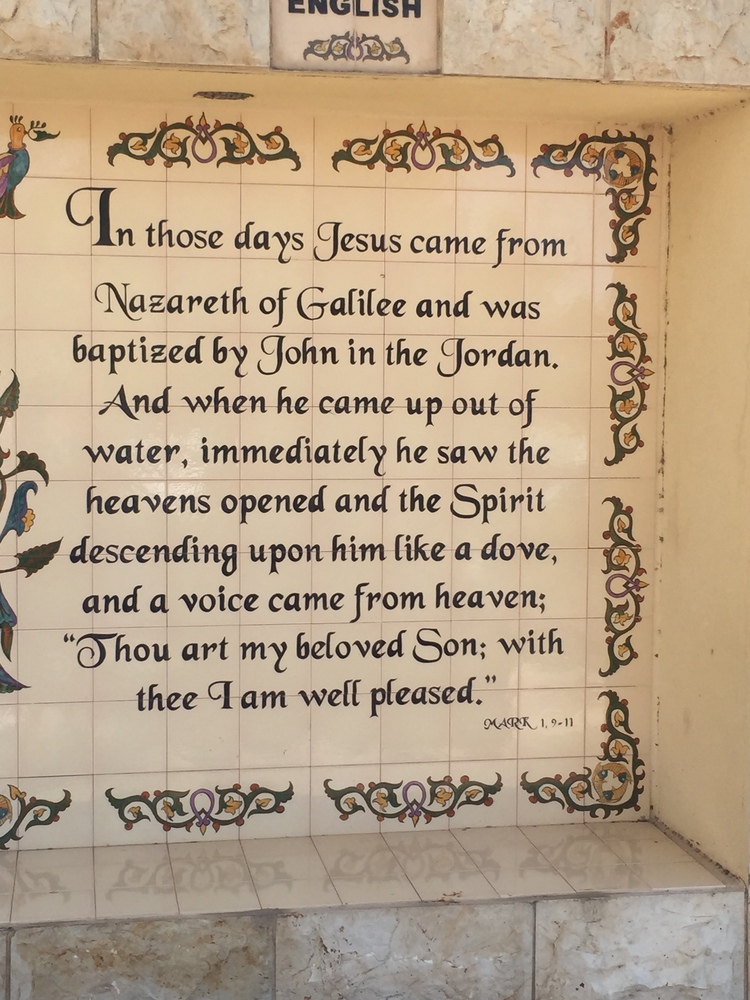

Colorful tile mosaic panels decorate the area surrounding the entrance from the parking lot as well as the promenade along the river. A biblical verse inscribed in the mosaic proclaims: “In those days Jesus came from Nazareth of Galilee and was baptized by John in the Jordan.” This verse from the New Testament Gospel of Mark aims to create a feeling of history and sacredness, says Chen, who has carried out anthropological field research at Yardenit.

“Because this is not the real place, [the managers] do a lot of things to strengthen the connection” to Christianity, he explains. Chen also points out the strong element of entrepreneurship and commercialization at Yardenit, which is in stark contrast to the way the downstream sites operated hundreds of years ago, when pilgrims would make donations to support the monasteries maintaining them.

“Here, you have Jews running a Christian site,” Chen says. “And it is interesting to see how the kibbutz has come to understand the Christian world and the diversity in the Christian world.” The management’s knowledge is evident in the variety of items they stock in the store, ranging from paintings intended to resemble Greek Orthodox icons to jewelry engraved with Old Testament verses written in Hebrew.

Duger says the kibbutz has a very businesslike approach to the site. “It’s not a spiritual connection, it’s a business connection,” she says. According to Chen, there have been a handful of other attempts over the years by other kibbutzim and local Israeli communities to woo pilgrims onto their riverfront property for baptism, but the sites have not caught on or had the success of Yardenit or Qasr al-Yahud.

“To take a sacred place from place to place is not the invention of Yardenit—it has happened since Rome was the new Jerusalem for the church,” Chen says. He is referring to the fact that Rome became the center of the Christian world, even though much of its history was rooted in Jerusalem and its surroundings. “But the unique thing here is that Jewish Israelis built the place for Christian pilgrims.”

Scholars have long sought explanations for how sacred traditions develop. Early 20th-century French philosopher and sociologist Émile Durkheim posited that religious ritual stemmed from the “collective effervescence” a group felt when partaking in events together. British Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm argued that tradition could be invented to serve the needs of society and its authorities. British anthropologist Mary Douglas set forth in her landmark book Purity and Danger that sacred objects, rituals, and places develop partly out of the human need for a feeling of order, even if such religious practices do not grant immediate tangible results, or miracles.

But a common denominator in all of these explanations is that the sacred, whether a certain ritual or a specific place, is something that is socially constructed. Sacred sites often emerge over time through some combination of past events, narratives of people’s experiences, and the policies and actions of religious authorities. The material and the spiritual are often deeply interconnected in such places, explains Ellen Badone, a professor of anthropology at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. Badone has studied the emergence of pilgrimage to Kerizinen, in northwestern France, where the Virgin Mary is believed to have appeared.

“Usually the place that becomes sacred is where individuals or groups perceive that the temporal realm has encountered the divine realm,” Badone says. And the site must, in a sense, continue to offer this experience of the interaction between these two realms to each pilgrim. “It has to satisfy their desires, or they won’t come,” she adds.

The material aspects of sacred places can often enhance the spiritual experience. This is why religious sites often contain images or objects that are copies or imitations of their more ancient versions, says Yael Zerubavel, professor of Jewish studies and history at Rutgers University in New Jersey. She has studied the phenomenon of new spiritual tourist places and how they use iconic representations to evoke the past. “Paradoxically, the newly constructed site may generate a more complete sense that one has experienced the real thing than an authentic site that is less easily accessible or in a state of ruin,” Zerubavel explains.

In addition to the objects, art, and architecture that enhance the spiritual, sacred sites have long been connected to commerce. Trade routes often developed along the roads taken by pilgrims, and pilgrims often purchased souvenirs as a way to capture some of the sacred qualities that are perceived to be associated with the site or the route along which they were bought, Badone says.

In the Western Judeo-Christian tradition, there is a common conception that something is spiritual or commercial. “But that’s a false dichotomy—it can be both,” Badone adds. “Throughout history holy places have also been markets.”

The number of visitors to Yardenit remains high even though Qasr al-Yahud, the older site down near the Dead Sea, reopened in 2011. Qasr al-Yahud is about an hour-and-a-half drive from Yardenit, deep in the Judean desert in a long-contested area of the West Bank that Israel controls but that Palestinians hope to make part of a future sovereign state. The site’s access road is still lined with barbed wire and signs warning of landmines left over from the Six-Day War and its aftermath. Churches at Qasr al-Yahud remain fenced-off and mined, although HALO Trust, a British charity that specializes in clearing landmines, has recently been approved by Israeli and Palestinian officials to demine the entire area once enough money is raised.

At Qasr al-Yahud, the Jordan appears brown and muddy, not clear like at Yardenit, and the site attracts fewer visitors, despite an Israeli government investment of 10 million shekels (US$2.62 million) to build a chapel, construct wooden ramps into the river, and upgrade the toilet facilities. The other ancient site, Bethany Beyond the Jordan, which is across the narrow section of the river here, reopened to tourists in 2002. Last year it was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site, but the Jordan tourism ministry says it attracted only about 66,000 visitors, while the Israel Nature and Parks Authority reports that Qasr al-Yahud drew about 400,000. Both lag behind Yardenit in number of visitors.

Alon, the marketing team member at Yardenit, says Yardenit’s management is taking steps to ensure it remains the go-to baptismal site. He takes me on a few minutes’ walk from the gift shop and main baptismal area to a newly built amphitheater on the bank of the river that seats 170 people. Here, there is a stone altar and a fountain that can be filled with Jordan River water, which can in turn be used to perform sprinklings of water on a person’s head—another form of baptism. The new facility, built at a cost of about US$80,000, opened in June and allows groups to use this area for religious concerts and services. Alon estimates that the amphitheater will draw some 10 to 15 percent of Qasr al-Yahud’s visitors to Yardenit.

On most days Yardenit is open later in the evening than Qasr al-Yahud, and it offers perks such as free cold beverages to tour guides and bus drivers. The water here is cleaner because Yardenit sits right below where the Sea of Galilee joins the river, whereas the area further downstream struggles with inflows of sewage and other pollutants. “Logistically speaking, it’s just better here than Qasr al-Yahud,” the tour guide Savion tells me. “It’s definitely better made and cleaner.” But Savion adds that he often makes an effort to tell his groups that Yardenit is relatively new, and when his bus passes by the ancient site, he also tells them the history of Qasr al-Yahud, even though they don’t visit it.

Beptiste and other pilgrims at Yardenit are aware of the site’s short spiritual history but say that for the most part it has not detracted from their experiences. “The water flows from one location to the next,” Beptiste says. “It doesn’t matter if you are at the exact location or not.”

Ashley Barnett, a graduate student from Florida, says she chose to come here rather than Qasr al-Yahud because she heard that the water was cleaner in the northern part of the river. “Wow, this is so crazy!” Barnett exclaims as she wades into the water wearing a white gown over a bathing suit. “This has been on my bucket list for so long.” Because they were on their own without any sort of minister or guide, Barnett and her husband took turns immersing each other under water, with a friend standing close to them reciting a Bible verse from memory. She acknowledges that Yardenit feels a bit commercial but says she is still happy with her choice to get baptized at this location. The organized nature of Yardenit has allowed her to relax here and concentrate on the spiritual element and to connect with the water, Barnett says.

“It stinks that it’s monetized, but it’s what you make of it. To go in at Qasr al-Yahud, that would be like the cherry on top, but I don’t know that that is really the authentic place either,” she says. “How do we really know that?”