Neanderthals Traversed Vast Distances

This article was originally published at The Conversation and has been republished under Creative Commons.

Neanderthal (Homo neanderthalensis) fossils were first discovered in Western Europe in the mid-19th century. That was just the first in a long line of surprises thrown up by our closest evolutionary cousins.

We reveal another in our new study of the Neanderthals who lived in Chagyrskaya Cave in southern Siberia around 54,000 years ago. Their distinctive stone tools are dead ringers for those found thousands of kilometers away in Eastern and Central Europe.

The intercontinental journey made by these intrepid Neanderthals is equivalent to walking from Sydney to Perth or from New York to Los Angeles, and is a rare example of long-distance migration by Paleolithic people.

Knuckleheads no more

For a long time, Neanderthals were seen as intellectual lightweights. However, several recent finds have forced a rethink of their cognitive and creative abilities.

Neanderthals are now believed to have created 176,000-year-old enigmatic structures made from broken stalactites in a cave in France and cave art in Spain that dates back more than 65,000 years.

Their intercontinental odyssey over thousands of kilometers is a rarely observed case of long-distance dispersal in the Paleolithic.

They also used bird feathers and pierced shells bearing traces of red and yellow ochre, possibly as personal ornaments. It seems likely Neanderthals had cognitive capabilities and symbolic behaviors similar to those of modern humans (Homo sapiens).

Our knowledge of their geographical range and the nature of their encounters with other groups of humans has also expanded greatly in recent years.

We now know that Neanderthals ventured beyond Europe and Western Asia, reaching at least as far east as the Altai Mountains. Here, they interbred with another group of archaic humans dubbed the Denisovans.

Traces of Neanderthal interactions with our own ancestors also persist in the DNA of all living people of Eurasian descent. [1] [1] As an update: Recent studies have shown that modern populations across Africa also carry DNA from Neanderthal ancestry. However, we can still only speculate why the Neanderthals vanished around 40,000 years ago.

Banished to Siberia

Other questions also remain unresolved. When did Neanderthals first arrive in the Altai? Were there later migration events? Where did these trailblazers begin their trek? And what routes did they take across Asia?

Chagyrskaya Cave is nestled in the foothills of the Altai Mountains. The cave deposits were first excavated in 2007 and have yielded almost 90,000 stone tools and numerous bone tools.

The excavations have also found 74 Neanderthal fossils—the richest trove of any Altai site—and a range of animal and plant remains, including the abundant bones of bison hunted and butchered by the Neanderthals.

We used optical dating to determine when the cave sediments, artifacts, and fossils were deposited, and conducted a detailed study of more than 3,000 stone tools recovered from the deepest archaeological levels. Microscopy analysis revealed that these have remained intact and undisturbed since accumulating during a period of cold and dry climate about 54,000 years ago.

Using a variety of statistical techniques, we show that these artifacts bear a striking similarity to so-called Micoquian artifacts from Central and Eastern Europe. This type of Middle Paleolithic assemblage is readily identified by the distinctive appearance of the bifaces—tools made by removing flakes from both sides—which were used to cut meat.

Micoquian-like tools have only been found at one other site in the Altai. All other archaeological assemblages in the Altai and Central Asia lack these distinctive artifacts.

Neanderthals carrying Micoquian tools may never have reached Denisova Cave, as there is no fossil or sedimentary DNA evidence of Neanderthals there after 100,000 years ago.

Going the distance

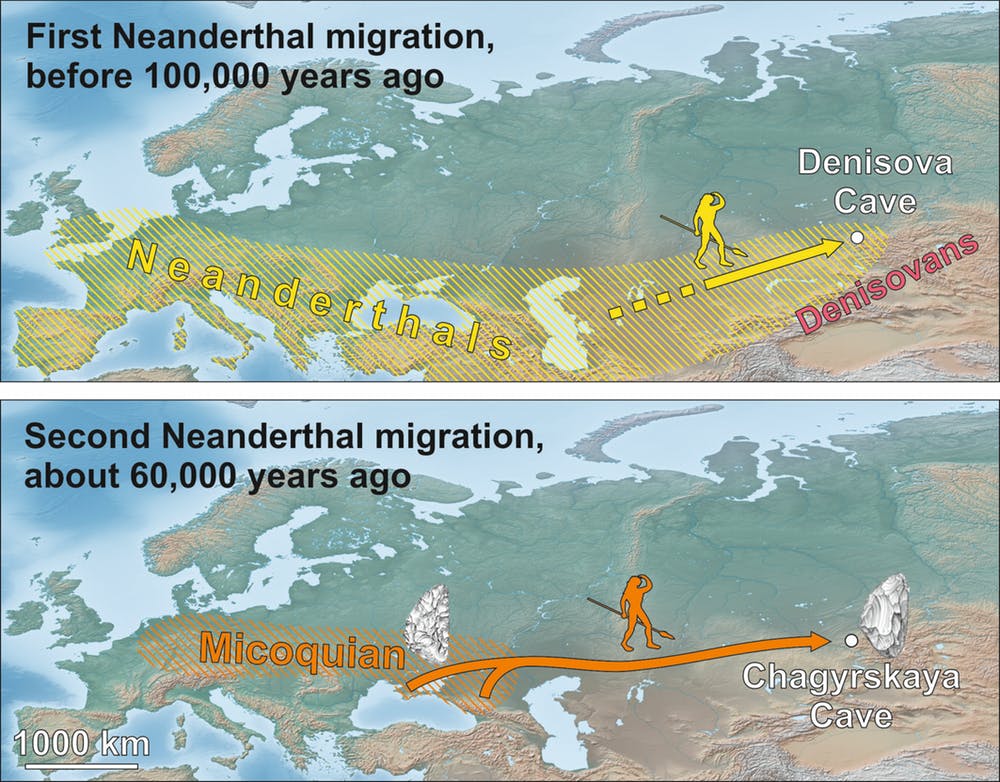

The presence of Micoquian artifacts at Chagyrskaya Cave suggests at least two separate dispersals of Neanderthals into southern Siberia. Sites such as Denisova Cave were occupied by Neanderthals who entered the region before 100,000 years ago, while the Chagyrskaya Neanderthals arrived later.

The Chagyrskaya artifacts most closely resemble those found at sites located 3,000–4,000 kilometers to the west, between the Crimea and Northern Caucasus in Eastern Europe.

Comparison of genetic data supports these geographical links, with the Chagyrskaya Neanderthal sharing closer affinities with several European Neanderthals than with a Neanderthal from Denisova Cave.

When the Chagyrskaya toolmakers (or their ancestors) left their Neanderthal homeland in Eastern Europe for Central Asia around 60,000 years ago, they could have headed north and east around the land-locked Caspian Sea, which was much reduced in size under the prevailing cold and arid conditions.

Their intercontinental odyssey over thousands of kilometers is a rarely observed case of long-distance dispersal in the Paleolithic and highlights the value of stone tools as culturally informative markers of ancient population movements.

Environmental reconstructions from the animal and plant remains at Chagyrskaya Cave suggest that the Neanderthal inhabitants survived in the cold, dry, and treeless environment by hunting bison and horses on the steppe or tundra-steppe landscape.![]()

![]()

Our discoveries reinforce the emerging view of Neanderthals as creative and intelligent people who were skilled survivors. If this was the case, it makes their extinction across Eurasia even more mysterious. Did modern humans deal the fatal blow? The enigma endures, for now.