Digging up the Dead

Excavating a 17th–century cemetery in the small town of Drawsko, Poland, was not how I expected to spend this summer—or any summer, really.

Along with 20 other university students from across Canada and the United States, I attended a mortuary archaeology field school with the Slavia Foundation—a nonprofit that supports archaeological research in Poland. For three and a half weeks, we were tasked with carefully uncovering, documenting, removing, and analyzing the skeletal remains of people who lived hundreds of years ago and whose cultures and origins are unknown. In the midst of a European heat wave, we worked in sand and dirt scorched by the sun, with our backs aching as we carefully dug inch by inch.

For me, the work was an exciting adventure—an opportunity to explore a field of research I had read about but never thought I would get to experience. But it also brought up questions I hadn’t considered before, about how people around the world treat the bodies of the dead.

To date, there have been an estimated 108 billion modern Homo sapiens in the entirety of human history who have lived and died—and another 7.7 billion alive today. That’s a lot of bodies. Throughout time, people have had different ideas and concerns about what happens to these remains. Hominins have been burying their dead for tens or, possibly, hundreds of thousands of years. In recent centuries, some bodies have been cremated, others have been handed over for medical experimentation or organ donation, some have been treated as tourist attractions, and still others have been dug up in the name of science.

After my summer of digging, I realized there’s no one right answer about what to do with human remains. But there is a common feature in modern expectations of good practice: respect.

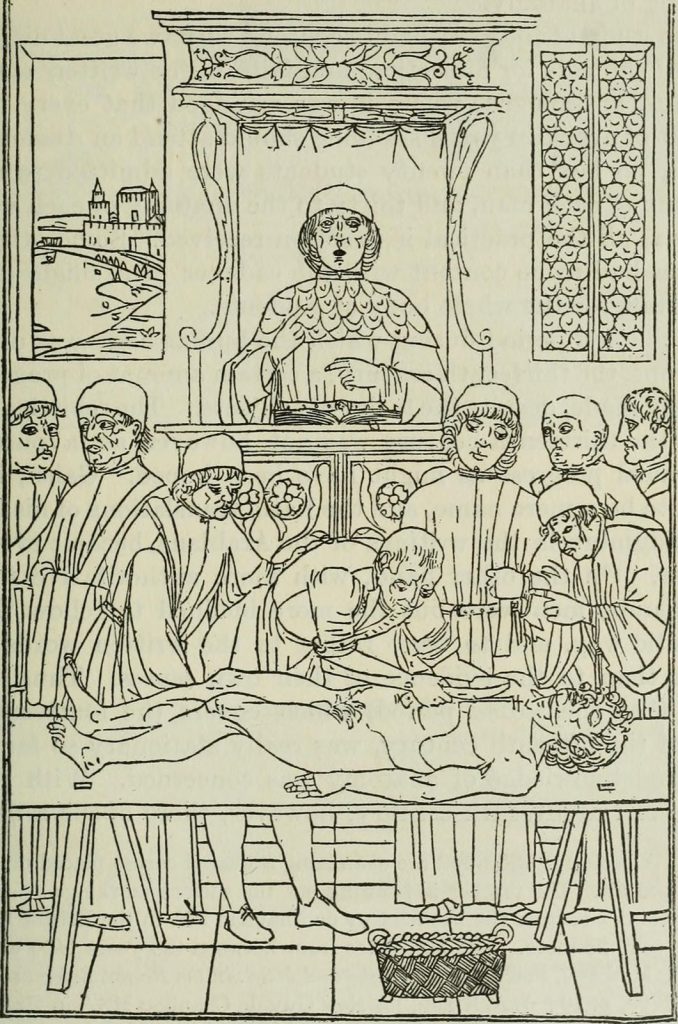

Back in the Renaissance, bodies became a commodity for medical research in Europe. The practice was controversial, however, as many people of the Christian faith feared their body and soul would not be reunited in heaven if their body had been dissected or desecrated in any way. By the 16th century, the bodies of hanged criminals began to be handed over to surgeons in Protestant European countries for use in anatomical studies and classes. The demand for such “specimens” outgrew the supply, and cadavers began to be obtained through grave robbing by body snatchers.

Today, standard practice dictates that bodies for medical, educational, or research purposes be obtained by donation and that respect be shown to those being studied. Nonetheless, in some countries, unclaimed bodies are still handed over to medical schools for anatomy classes—a practice that has drawn extensive criticism.

Practices in archaeological investigation have also changed dramatically. During the 1800s, most archaeologists treated human remains as valuable artifacts and spared little concern for the ethics of digging them up. Museums developed collections to study Indigenous cultures without much thought to how items, including human remains, were obtained. It was only in the 1960s that archaeologists began to develop professional ethical guidelines. Attitudes about human remains began to seriously shift in the 1980s, and while Canada has not enacted formal legislation, a U.S. federal law was passed in 1990 regarding Native American remains and cultural items. Regardless, there are still heated debates about whether to repatriate human remains to their home communities and how best to respect the wishes of the dead.

Today, less invasive methods are often used to gain archaeological understanding without physical disruption of a gravesite. In Canada, for example, some researchers use ground-penetrating radar to confirm the locations of Indigenous gravesites that were lost over time—including those of children who went missing as part of the country’s destructive residential school system. The same technology is also used in Poland when trying to find and mark lost burial sites from the Holocaust in an attempt to respect Jewish law, Halakha, which forbids disturbing graves.

At the Slavia Field School in Drawsko, we didn’t know the cultures of those we studied: The cemetery is estimated to be roughly 400 years old and is far from any specific known community from that time. Over the past few centuries, many groups and cultures have lived in the area of land that makes up modern Poland. There was no way of knowing who was buried beneath our feet or what their specific customs or concerns might have been regarding their remains.

The Polish government gave permission for the excavation, and the field school directors developed strict guidelines for our work. We did not give the skeletal remains nicknames, but rather used an alphanumeric code, as we did not know what names might have been offensive during a particular time period or to a certain culture. We did our best to uncover everything with minimal damage and to thoroughly document our work. We showed the utmost respect for the remains we worked with: Lying in graves was prohibited, and we did not joke around the graves of those we exhumed. (That might sound obvious, but it isn’t always, perhaps especially with less-experienced students. For example, people have joked about the position of some of the human remains at Pompeii.) Our approach was based on the ethical principle that all people deserve our respect, even after death.

Despite the care that researchers take, there is an ongoing debate about whether mortuary archaeology is akin to grave robbing. Some argue that the intent behind the work is what makes the difference: personal gain versus scientific benefit. But there are varying opinions about where the line should be drawn.

Is there a specific date when you can say that an individual has been buried long enough that they can become the subject of dispassionate study? Perhaps there is a date beyond which a dead person no longer has a right to their grave?

No one, after all, seems to have ethical qualms about digging up ancient hominin ancestors such as Neanderthals, while excavations of bodies from the sunken Titanic may feel more like an intimate disturbance. Different countries and nations around the world set their own standards. Some Indigenous cultures argue that their ancestors’ remains should not be available for scientific study at any time and that their loved ones’ spirits should be allowed to rest in their burial place.

In some countries, gravesites are reused to save on space in graveyards. For example, under South Australia’s Burial and Cremations Act 2013, a burial site may be reused once an internment right expires. (An internment right is usually an established period of paid ownership, which can be extended by a living relative if they so choose.) Once expired, a burial site and its headstone can be given what is called the “lift and deepen” treatment: The remains are dug up and reburied lower down in the grave, with the headstone either smashed, relocated, or buried with it, and another burial is placed on top.

Graves are also being reused in the City of London Cemetery and Crematorium in England. In this case, graves must be at least 75 years old and notices of a possible reuse are posted on the headstone and in advertisements six months before. If there are no objections, the headstone is reversed and a new inscription is engraved on the back before workers deepen the grave to make room for another body.

In the 18th century, the catacombs beneath Paris were created as a solution to the overcrowding of cemeteries and public health concerns. Skeletal remains were taken from overcrowded and crumbling cemeteries, then stacked and arranged in patterns along underground corridors of abandoned quarries. This became the final resting place for more than 6 million people—and now attracts tourists from around the world. Whether this tourism is respectful or macabre voyeurism depends on one’s perspective.

Recently, as a tourist myself, I walked through the Old Jewish Cemetery in Prague. At this site, the headstones are packed close together, and the ground is raised with bodies stacked 10 to 12 people deep in some places. In the 15th century, the government restricted the amount of land Jewish people were able to purchase for cemeteries. Since the removal of old graves was not allowed according to Jewish custom, new layers of soil were added and bodies were buried on top of one another for more than three centuries, creating a thick patchwork of crooked gravestones.

The cemetery where I worked in Poland was originally discovered in 1929 when a local farmer found that his machines were unearthing Bronze Age pottery pieces and skeletal remains. While this piqued some academic interest over the years and prompted some minor excavations, it wasn’t until 2008, when the Slavia Foundation took over the site, that focused archeological work and study began. Researchers have found the remains of more than 300 people at the site.

Our relationship with the dead will always be evolving.

Archaeologists and anthropologists are now compiling all the information they can about these graves. Some of the bodies were buried with “anti-vampiric” techniques: Large stones and iron tools, such as sickles, were placed on top of them to prevent them from rising from the dead and preying on the living. One of the bodies from our excavation was discovered with material from a hat still draped over the skull, buttons from a coat dotted down the chest, a brass pin near the hand, and a stone over the abdomen.

Work on excavating human remains from this cemetery has now been completed, though research continues. The plan is for these remains to be temporarily displayed at a small museum, along with other archaeological finds from Poland, and then, out of respect, reburied in a new cemetery elsewhere.

The issues of where we put our dead, and how we choose to treat those remains in the future, are still in flux. Today more people in the Western world are choosing eco-friendly burials, designed to encourage rapid decomposition, or cremation; ashes can be scattered or even transformed into diamonds or works of art. Different cultures continue navigating their way through these issues in their own unique ways.

Our relationship with the dead will always be evolving. We will continue to learn from the dead—not only about our history but also about the values of our modern societies.