Club-Wielding Ancestors: Myth or Reality?

Growing up in the 1990s, I first encountered the ancient world through a video game called Prehistorik. The game resembled Super Mario, only the main character was not an Italian plumber but a shaggy caveman. Clad in a leopard-print loincloth, the fellow roamed his 2D world, searching for food and clobbering dinosaurs with a hefty wooden club.

As a kid, I quickly learned that Prehistorik was unrealistic: Humans could never have met dinosaurs, which went extinct over 65 million years before our species appeared on the planet. Nor did ancient humans primarily dwell in caves. But what about the wooden club—a weapon often wielded by pop culture cavepeople, including the Flintstones and Lego Caveman? Was the club part of our ancestors’ arsenal or just a popular myth?

This question vexed me decades later after I became an archaeologist who studies the time period Prehistorik supposedly depicts. In a new study, I examine the evidence and conclude that wooden clubs likely existed at least since the dawn of Homo sapiens. But far from simple clobbering logs, those weapons probably required considerable expertise to craft and maneuver.

vanishing Evidence

To investigate the ancient wooden club myth, I searched archaeological reports for any mention of the artifacts. I didn’t expect to find much, however, because wood rapidly decays in most environments. For a wood artifact to survive beyond 1,000 years, the item must have settled in an extremely dry place, been charred to a crisp, or gotten waterlogged somewhere such as in a bog.

In contrast, stone objects can last forever. This is why we speak of the Stone Age and not the Wood Age or First Tool Age, although the latter two would be more accurate. “Stone Age” people probably crafted most items from wood and other organic materials. Those perishable items are just orders of magnitude rarer than stone artifacts many millennia later when archaeologists dig a site.

That also applies to ancient wooden clubs, which have decayed away save for a handful of cases. In the archaeological reports I searched, the oldest possible club was a short heavy piece of wood found at the waterlogged site of Kalambo Falls, Zambia. Thought to be at least 300,000 years old, the stumpy artifact may have armed a pre–H. sapiens human ancestor.

More evidence comes from later periods, especially moorland, lakeshore, and riverside settlements in Europe, which date between 6500 B.C. and 1000 B.C., from the Mesolithic to the Bronze Age. It seems some of the clubs from this span served as weapons based on their depictions in rock art and the distinct head wounds on skeletons. In one experiment, researchers whacked synthetic skulls with a club replica, showing that indeed a club could have inflicted the ancient injuries.

Moreover, two 3,000-year-old clubs were found right at a Bronze Age battlefield in northern Germany. One shaped like a baseball bat and the other like a mallet, these clubs were almost certainly weapons of war, considering they surfaced at a battle site. For other finds, however, knowing the function is more difficult. With clubs, people may have battled, hunted, hammered, pounded food, played, or performed rituals.

wooden clubs in modern hands

Although few archaeological clubs survive, other types of evidence can assist. For instance, I reviewed cases of apes using wooden branches or logs as tools. It turns out numerous scientists have witnessed chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and orangutans throwing branches or beating other animals with sticks. Since our closest living relatives whack creatures with wood, it’s probable our ancestors did too.

But knowing that past people could use clubs doesn’t explain why they did. After all, ancient foragers also wielded long-range weapons such as spears or bows and arrows, which offer obvious advantages. When hunting with clubs, it is difficult to get close enough to game before the creatures run away. And such close encounters are risky. One well-aimed kick or horn thrust could be fatal.

To better understand why clubs proved handy in hunts and fights, I looked to modern humans who live, or until recently lived, as hunter-gatherers. Today and for the past few hundred years, it’s estimated that around 5 million people worldwide have been living as hunter-gatherers, meaning they have foraged most of their food from wild plants and animals.

Continually innovating and adapting, these diverse societies are not relics of bygone ways. Modern foragers can, however, inspire insights about the ancient club question. They showcase the varied ways foragers use wooden clubs for hunting or other activities.

To get an idea of worldwide club use, I delved into ethnographic literature that describes modern and recent forager societies. Most of the ethnographies I analyzed were penned by anthropologists during the 19th and 20th centuries, though missionaries and early travelers also contributed some.

These information sources are far from perfect. Some authors romanticized the people they described, while others wrongly depicted them as “primitive.” For some societies, I can be more certain about club use because several independent anthropologists made the same observations. In other cases, however, I must cautiously rely on a single source. Despite these limitations, the records nevertheless document how diverse forager societies used clubs in recent centuries.

Examining descriptions of 57 forager societies spread around the globe, I found references to wooden clubs in the vast majority of them. But most communities have clubbed sparingly.

Hunters chose clubs for particular prey species or as secondary weapons to kill animals that were already captured or wounded. For instance, the San in Southern Africa reportedly have used their 50–100-centimeters-long round-headed wooden clubs to hunt porcupines, ant bears, and other small animals. [1] [1] Southern African wooden clubs are often called knobkerries, a term that combines Afrikaans and Khoikhoi words. East Siberian Nivkhs were observed to have clonked seals and sea lions with clubs, and killed rats, otters, and molting birds with sticks. Ethnographic reports say Aboriginal Australians have used clubs, throwing sticks, and boomerangs against animals such as kangaroos and wallabies. With clubs, many Indigenous people of the Northwest Coast have whacked beavers, bears, deer, and marine mammals, while several Indigenous groups in South America have used them to clobber armadillos and peccaries, according to ethnographies.

But clubs found far more use in combat. In the ethnographies I reviewed, 80 percent of societies have used them for interpersonal violence. This is true even when the fighters also had long-range weapons. Especially in big battles, when arrows and other projectiles eventually depleted, fighters engaged in close combat. For example, when Caribbean Kalinago warriors emptied their arrow supply, they have switched to spears and decorated clubs called boutou.

Moreover, many traditional wars were not simply about defeating the enemy. They have been an opportunity to demonstrate courage and heroism. A brave warrior was not one who cowardly shot from a distance but one who bested the enemy in hand-to-hand combat.

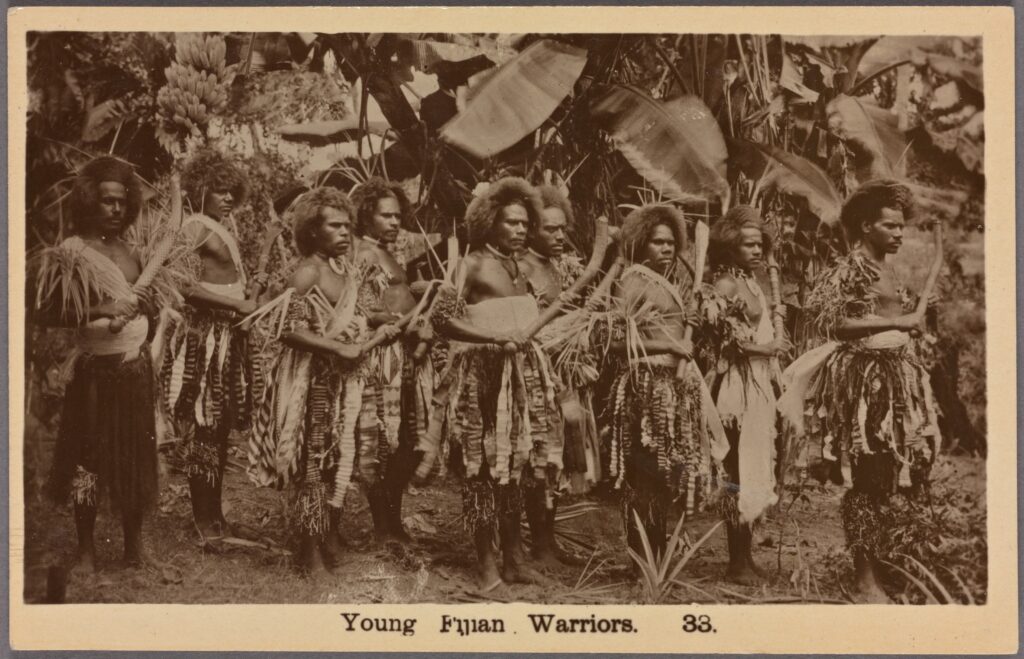

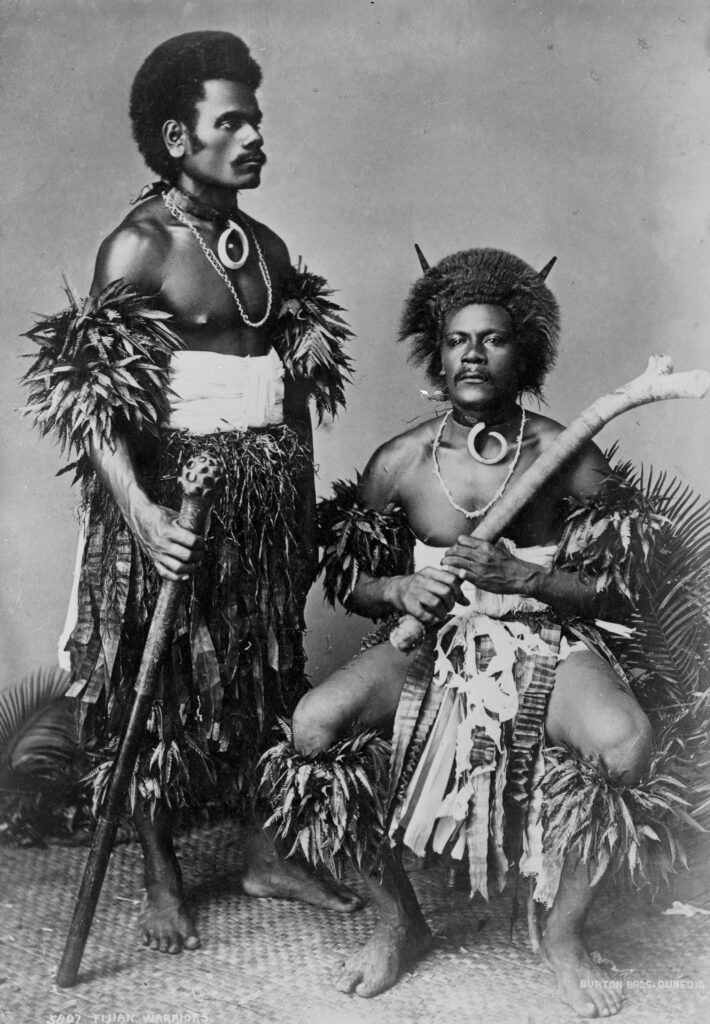

In Fiji, the leading warriors reportedly continued to fight with clubs after the musket was introduced in the mid-19th century; killing with a club was the only way to win knighthood. Similarly, among Comanches of the southern Plains, striking an enemy with a handheld spear or club merited the highest war honors, what is known as counting coup.

Finally, many societies supposedly have used wooden clubs or sticks to resolve conflicts where the goal was not to kill rivals but only to defeat them. Among Yanomamö in Amazonia, dueling with 2–3-meter-long clubs was said to be a relatively harmless form of violence, along with chest pounding and side slapping. In contrast, bows and arrows were used for killing.

Crafty Clubs

Though a simple log might suffice, in nearly half the societies described in the ethnographies I examined, the clubs were far more sophisticated—specially shaped, decorated, multi-component, or composed of choice wood.

For instance, in Fiji, individuals crafted a great variety of clubs. In addition to war clubs, which took the form of strikers, prodders, penetrators, and throwers, Fijians fashioned clubs for peacetime, ceremonies, and sacred rites. After the death of chiefs, their favorite club reportedly often became a shrine, where their ghosts could dwell and engage with the living.

Club manufacture was a highly developed industry. Some Fijian clubs required years to create. As 20th-century Australian missionary and anthropologist Alan R. Tippett observed in his book Fijian Material Culture:

The maker of clubs had to recognize the potential of every tree—the root, the straight limb, the forked limb. He had to know the woods. Much of his work was done while the tree was yet growing. For months, sometimes for years, he would work on the waka, or roots of a selected tree before uprooting it. … the craftsman drew from the fellowship of other club makers and the accumulated knowledge of the craft group handed down from past generations.

the ancient wooden clubs myth

The ethnographic record indicates that for the past few centuries, diverse forager societies have used clubs for fighting and hunting particular prey. A smattering of archaeological finds confirms that clubs armed humans for millennia—and possibly pre–H. sapiens ancestors for longer. The fact that our close ape relatives whack animals with branches and logs suggests human ancestors had the brains and dexterity to club for perhaps millions of years.

Combining those lines of evidence, I’m convinced the earliest modern humans likely wielded clubs—probably more often for conflicts than hunting.

Returning to the game Prehistorik, we can be sure that no human ever clubbed a dinosaur, but past people probably whacked creatures that existed over the past 300,000 years. The wooden club in their hands is not a myth. However, it may have been a much more sophisticated weapon than most people imagine.