What Ancient Goat Teeth Reveal About Animal Care

Animals were harmed in the making of this story.

Some 4,000 years ago, goats living near what is today the Persian Gulf developed horrible dentition. These poor goats had teeth split down the middle, worn to nubs, or missing entirely. Yet the afflicted individuals outlived their healthier herd companions.

To survive so long with such dental distress, these animals had to be looked after by someone. In fact, it seems these particular goats received special love and care—and as a result, they wound up less healthy and perhaps less happy than more free-ranging animals.

As an archaeologist studying human-animal relationships, I have examined thousands of bones. I have also worked on excavations unearthing faunal remains. Recently, I have been studying animal jaws from a site in southeastern Iran. That is how I met the goats with terrible teeth.

As I worked to solve the mystery of these animals, I realized they hold a lesson for our present-day relationships with kept creatures: People may inflict harm on the animals they care about most.

THE RISE OF TEPE YAHYA

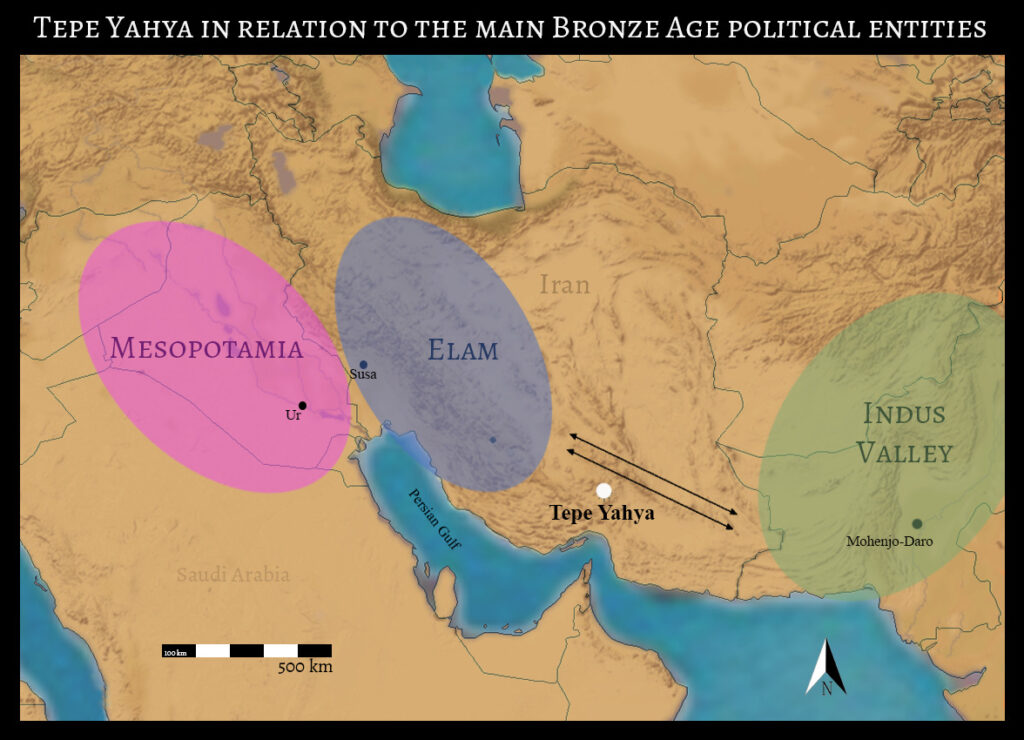

In 2021, I began examining bones from animals who lived between 3,000 and 7,500 years ago at Tepe Yahya, a site in a dry valley of the Zagros Mountains in present-day Iran. During this 4,000-year period, Tepe Yahya changed substantially. In what began as a small village, a few hundred locals farmed and raised livestock. However, Tepe Yahya was in an ideal location to be a waypoint on a trade route linking Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley.

It gradually grew into an urban hub with strong connections to the larger political entities of Elam and Mesopotamia farther west. The residents made and exported elaborately carved stone vessels, which have been found thousands of miles from Tepe Yahya. By 4,500 years ago, the once small, secluded village had more expansive farmlands, bustling craft workshops, and an artistic style similar to that found at nearby sites, suggesting a sense of regional identity.

Yet through all this growth and expansion, residents continued to rely heavily on sheep and goats.

A NEW STUDY OF OLD GOATS

Archaeologists excavated Tepe Yahya between 1969 and 1975. In the 1980s, Harvard University zooarchaeologist Richard Meadow examined the animal bones to identify species. Since his initial work, however, the bones have only been studied by students as part of coursework and training.

A wealth of information can still be gained from bones excavated long ago, such as those from Tepe Yahya. I saw an opportunity to return to this overlooked collection and to explore a subset of the bones in detail.

I focused on the lower jaws of sheep and goats—the most abundant and important species in the Tepe Yahya collection. Lower jaws, or mandibles, are particularly useful because the teeth consistently wear down over time in certain species. Using this wear pattern, zooarchaeologists can estimate an animal’s age when it died.

Excavators uncovered the Tepe Yahya bones from ancient trash heaps located within and beside houses. This means the animals likely contributed to household needs. As a result, they died in relatively good health and before old age: Some were killed between 6 months and 1 year—the prime ages to become dinner meat—and others averaged between 2 and 5 years—better for production of milk and hair.

What I did not expect was a small group of goats with devastatingly poor teeth. These animals were 6 years or older, also an unusual attribute. The older an animal gets, the more care it requires—especially if it has injuries like split and missing teeth. (Because the jawbones healed around the missing teeth, I could tell they were lost before the animals died rather than after death.)

Moreover, the dental damage centered on the first molar. What caused this damage? And why were these animals kept alive so long?

CARE THAT HURTS

I contacted a large animal vet with the unusual request of discussing long-dead animals. It turns out severe dental damage rarely afflicts present-day goats and sheep. Owners usually kill the animals before this level of damage accumulates. The fact that the injuries centered on a single tooth area implicated some sort of repeated aggravator, not just old age or poor oral hygiene, which affect teeth more evenly.

We determined a bit was probably to blame: Typically used for donkeys and horses, this leather or rope binding would have wrapped around the animals’ snout and rested in the mouth on first molars. Perhaps it helped harness the goats to carts or leash the animals.

Clearly, Tepe Yahya residents kept these goats close and alive for longer than all of the other the animals they owned. I suspect the goats were likely females who provided milk to their owners. Keeping them nearby would have offered easier access for daily milk consumption.

Dental injuries can be painful and even life-threatening. Eating becomes difficult. Other diseases can arise: As studies have shown, dental problems in dogs increases their risk of heart or liver disease.

At Tepe Yahya, the owners probably had to feed their prized goats higher-quality foods to minimize further health complications. By supplementing the diets in this way, the animals were kept “healthy” and able to keep rearing infants and producing milk.

FAVORED BUT NOT BETTER OFF

This small set of mandibles from Tepe Yahya provides new insight into the ways ancient people treated animals. Archaeologists often focus solely on the economic role of livestock, but the goats I studied might have garnered affection from their owners. And ironically, the goats likely suffered from that special treatment.

Across time and cultures, animals have not been valued equally. Today, in the U.S. city in which I reside, people cradle toy dogs like newborns and gift treats, toys, and multistory scratch towers to their cats. Meanwhile, they shoo pigeons and abhor the rat nibbling at trash scraps. Elsewhere, the most valued animals might be the most useful: the fastest horse in the race or the chicken who lays the most eggs.

Read more from the archives: “The Macabre and Magical Human-Canine Story.”

An animal’s elevated status does not mean they are free from harm, however. For example, puppy mills physically and psychologically traumatize mother dogs and their pups. Some puppies live shorter lives, as they easily get sick, and others may suffer genetic abnormalities from breeding.

Animals who reside in loving homes also can suffer. Pet obesity is reaching epidemic levels in the U.S., causing a slew of other health issues and likely shortening pets’ lives. Chronic stress or boredom may afflict animals kept in captivity.

Animals can certainly thrive alongside humans. But sometimes well-meaning owners create suboptimal conditions for their creatures. This may be what happened to Tepe Yahya’s old goats with terrible teeth. Then and now, when it comes to animal care, our loving motives may usher unexpected—and sometimes unfortunate—outcomes.