Funeral traditions around the world involve a range of rituals. From singing to burying to … eating. Why is food such a common practice in putting our loved ones to rest?

In this episode, Leyla Jafarova, a doctoral student at Boston University, examines the role of funeral foods in different cultural contexts—from the solemn Islamic funeral rites of the former Soviet Union to the symbolic importance of rice in West Africa. Food rituals help with bereavement because they carry cultural symbols, foster social cohesion, provide psychological comfort, and contribute to the expression of collective grief and remembrance within communities. Through food, human societies navigate the universal experience of death and mourning.

Leyla Jafarova is a Ph.D. candidate in sociocultural anthropology at Boston University. Her doctoral research focuses on the emergence and development of humanitarian ethics of care for the unidentified dead in post-war Azerbaijan and the production of knowledge in this regard. Leyla also explores how families of missing persons in post-war Azerbaijan construct their personal truths and navigate their experiences of loss and healing. She is examining how their alternative truths often exist alongside and are sidelined by dominant humanitarian regimes of truth that exclusively rely on forensic scientific evidence. This research has been supported through a Wenner-Gren Dissertation Fieldwork Grant and by a Graduate Research Abroad Fellowship through Boston University.

Check out these related resources:

- Dying to Eat: Cross-Cultural Perspectives on Food, Death, and the Afterlife, edited by Candi K. Cann

- Ways of Eating: Exploring Food Through History and Culture by Benjamin Aldes Wurgaft and Merry White

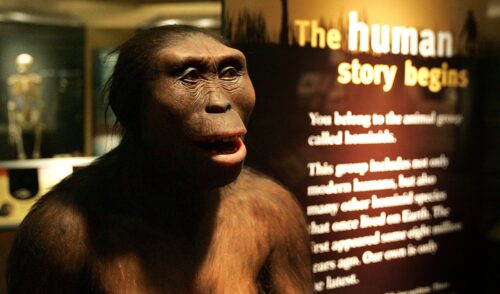

- “Who First Buried the Dead?”

SAPIENS: A Podcast for Everything Human is produced by House of Pod. The executive producers were Cat Jaffee and Chip Colwell. This season’s host was Eshe Lewis, who is the director of the SAPIENS Public Scholars Training Fellowship program. Dennis Funk was the audio editor and sound designer. Christine Weeber was the copy editor.

SAPIENS is an editorially independent magazine of the Wenner-Gren Foundation and the University of Chicago Press. SAPIENS: A Podcast for Everything Human is part of the American Anthropological Association Podcast Library.

This episode is part of the SAPIENS Public Scholars Training Fellowship program, which provides in-depth training for anthropologists in the craft of science communication and public scholarship, funded with the support of a three-year grant from the John Templeton Foundation.

Why Do We Eat at Funerals?

[introductory music]

Voice 1: What makes us human?

Voice 2: A very beautiful day.

Voice 3: Little termite farm.

Voice 4: Things that create wonder.

Voice 5: Social media.

Voice 6: Forced migration.

Voice 1: What makes us human?

Voice 7: Stone tools.

Voice 8: A hydropower dam.

Voice 9: Pintura indígena.

Voice 10: Earthquakes and volcanoes.

Voice 11: Coming in from Mars.

Voice 12: The first cyborg.

Voice 1: Let’s find out. SAPIENS: A Podcast for Everything Human.

Eshe Lewis: In many cultures, funerals have rituals, whether it’s burning candles, adorning a burial with flowers, or eating a special dessert. These activities each has significance and an origin story. There are a connection to a culture, a community, and a memory.

This next story comes from Leyla Jafarova, who brings us into funeral traditions across different cultures, from Azerbaijan to West Africa.

Leyla Jafarova: We are in my mom’s kitchen in Baku, Azerbaijan. It’s a Thursday afternoon, and she’s making halvah, a traditional dessert made to commemorate the deceased and served at funerals. As she sprinkles salt in the halvah, she reads a prayer to honor the memory of our ancestors and deceased family members.

[Leyla’s mother praying]

Leyla: As I sit with my mom in the kitchen contemplating why we associate this delicious dessert with funerals, I also think about my grandmother’s death. She passed away in the summer of 2018. We were going to bury her in our hometown of Ganja, which is in the western part of Azerbaijan. At the time, the local authorities in Ganja banned what they referred to as excessive funeral feasting due to potential financial strains on the bereaved families. Relatives of deceased individuals, especially in more remote areas and outside urban centers, usually set up tents outside their homes to accommodate all of the people coming to pay respect to the dead person. There are businesses that rent out these tents, and you can also hire service workers to serve food at the funeral.

Basically, there is an entire political economy around funerals, where a lot of people’s livelihoods depend on this “excessive” funeral feast. So after the ban, the only thing that was allowed to be served in this tent was tea and halvah as well as more traditional funeral foods, such as dates and sugar cubes. However, during my grandmother’s funeral, my parents still hired the cook despite the ban and started providing elaborate meals in the privacy of our home. So, semi-jokingly, I would refer to this as an “underground” funeral feast.

I did not quite understand why we had to go to such an extent to provide an elaborate feast. And I kept telling my parents, “It just won’t bring grandma back.” And they would respond to this with patience and say “But we have to do this for your grandma. We have to do this, so her soul rests in peace.” I want to use this personal anecdote as a starting point to start thinking about why we eat at funerals and what we eat at funerals.

Azerbaijan is a former Soviet country with a majority Muslim population. Funerals here serve as one of the major socialization events. I’m currently headed to talk with my friend Usmon Boron about the role of funeral rituals for Soviet Muslim communities.

Usmon Boron: I’d like to start by noting that when we talk about Soviet Muslims, we are talking about many different communities that lived across a wide geographical expanse.

Leyla: Usman, an anthropologist studying Muslim communities in Central Asia, comes from Uzbekistan and has worked extensively within the context of Kyrgyzstan, both formerly parts of the Soviet Union.

Usmon: And even there, Islam was very diverse during Soviet times. That being said, the Bolsheviks aimed to equally suppress all manifestations of Islam because an ideal Soviet citizen was expected to be an atheist. So the Soviet state destroyed most Islamic institutions and suppressed, and later tightly controlled, the ulama.

Leyla: Ulama are the clergy or religious scholars in Islam.

Usmon: These antireligious policies alienated many Central Asian Muslims from some of the key devotional aspects of Islam: the basics of theology, ritualistic practices—such as the daily prayers, Islamic ethics of dressing—as well as some prescriptions, such as the avoidance of alcoholic beverages, for example.

However, there were practices that the Soviet state could not eliminate, and the most significant of them were Islamic life cycle rituals, such as male circumcision, the marriage ceremony, and funeral rites. Life cycle rites were among the very few religious practices that most Soviet Muslims considered obligatory and unavoidable.

Leyla: And so funeral rituals were among the very few contexts in which many Soviet Muslims could encounter Islam.

Usmon: It is during these rites that lay Soviet Muslims could hear extended recitations of the Koran or see how the Islamic ritual prayer is performed.

Leyla: Soviet and post-Soviet Muslims have always held Islamic burials in such a high regard, despite the atheism of the state and despite not knowing almost anything else about Islam. And I think that’s something that you’re trying to explore more.

Usmon: So for many Muslims in Central Asia during Soviet times, staying committed to Islamic funeral rites was very important. It was, in a way, a red line that the Soviet state could not cross. Historian Marianne Kamp wrote a wonderful paper based on oral history, where she argues that remaining committed to the funeral prayer was of paramount importance. And during Soviet times, despite the official atheism, the Soviet state could not prevent people from performing this prayer.

Leyla: It was so important that sometimes even Soviet officials risked their careers by organizing grand Islamic funerals for their loved ones.

Usmon: Islamic funerary practices are not limited to one day. People come to visit the family and recite the Koran for up to one month after the actual funeral. During Soviet times, because of how extended this process was, [it] created a major context. Now what is interesting is that during Soviet times, because of the centrality of the Islamic funeral, Islam got associated with funerary rites to such an extent that even the two main Islamic holidays, Eid-al-Fitr and Eid-al-Adha, lost their status as happy holidays and became occasions for mourning and going to cemeteries and reciting the Koran for the souls of the deceased.

Leyla: So if we narrow down to the level of a family living in Central Asia or the Muslim part of the Caucasus, for example, how does this family get introduced to how to conduct this life cycle of rituals during the Soviet times when there is no clergy or religious education is banned? How do they come to know what they’re supposed to do?

Usmon: I would start by saying that Soviet antireligious policies, the severity of them, varied throughout the Soviet period. There were ups and downs, and because of this inconsistency, the Islamic clergy or Islamically learned people could transmit knowledge. And the Islamic tradition could still survive during Soviet times, even during periods when Islamic institutions were completely closed down and the clergy were suppressed. You don’t need a person who has a formal title of “sheikh” or “mullah” to perform, let’s say, a life cycle ritual.

Leyla: So, basically, anyone with some knowledge of performing funeral prayers, called Janazah, could do it.

Usmon: Chingiz Aitmatov, for example, has a wonderful novel called And the Day Lasts More Than a Hundred Years. And the novel is about a Soviet worker in a small town somewhere in the Gaza Strip where he has to bury his friend, and he wants to bury his friend in an Islamic way. And he spends the whole day carrying the body of his friend with his co-villagers to a sacred Islamic Muslim cemetery.

So this worker had no Islamic education and basically didn’t know much about Islam. But still, before the actual burial, he performed the Janazah prayer. And he [Aitmatov] beautifully describes his struggle to remember the prayer. And he also beautifully describes the sense that it was absolutely important to perform this prayer.

[music]

Leyla: With this new understanding of how funeral rituals became so important for Muslim communities of the former Soviet Union, I wanted to think about the importance of the food at funerals. To get some answers, I’m meeting with Merry White, anthropologist of food at Boston University. So food, she says …

Merry White: … comforts those people who are grieving. It connects them to the dead person. It makes death part of life, which I think is the important thing about food. It makes death less scary and less separate.

Leyla: I asked her to talk about food at funerals in the United States.

Merry: There’s so many different American funerals. I can talk about Jewish funerals. They are, of course, regional. There’s Ashkenazi, and there’s Sephardim … so the practices are really different.

Leyla: But there’s one thing they hold in common, she says.

Merry: But one basic thing is “sitting shiva.” When the person dies, the first evening, you have everyone come to your house, and everybody brings food because the people who are mourning their dead person are not supposed to cook. And it doesn’t matter what food, it’s just that you bring usually sweet things. You’re supposed to have sweet in your mouth when you remember the dead person. You’re supposed to think sweet things.

Leyla: While sweets, such as halvah and dates, are important in funeral cultures like Azerbaijan and Jewish traditions, there’s also a variety of staples and foods that can be central to other funeral cultures.

Merry: It might not only be sweets that figure in ceremony. I mean, obviously rice: rice in West Africa, rice in the American South. There’s a ceremonial rice dish in Japan that’s called sekihan. You cook the rice with small red beans, and that sekihan is given to a mother after she’s had the baby or at funerals or special birthdays, like the 60th birthday.

Leyla: So special life cycle events?

Merry: Yeah, because the redness of it is a celebratory color. So the color of the food counts.

Leyla: Or sometimes what matters is the smell. Usmon shares the tradition of making borsook in Kyrgyzstan.

Usmon: In Kyrgyzstan, there is a very widespread practice called jıtın çıgaruu, which literally means “releasing the smell.” The practice consists of frying small pieces of dough by soaking them in hot oil, and the frying dough releases a certain smell. People believe this smell actually nourishes the spirits of deceased people. People normally cook borsook during the main Islamic holidays. And some families actually cook borsook almost every week, on either Thursdays or Fridays, and the cooking of it is normally accompanied by a recitation of short Koranic verses and prayers that people dedicate to their deceased loved ones.

When I learned about the story behind this practice, I immediately remembered that my parents also cooked a particular meal once a week, and my father would always recite several short Koranic verses before we would consume that meal. And this meal is a traditional Uzbek meal: pilaf, or as we call it, plov.

Leyla: Usmon was curious whether his parents cooking every Thursday evening was somehow related to the Kyrgyz preparing borsook. So he asked …

Usmon: … and my mom actually said, “Yes.” For Uzbek people, there is also this belief that when you cook pilaf, you basically start with frying meat. When you start frying meat, the meat releases a smell, and it also nourishes the spirits of deceased people.

In this way, I grew up witnessing a certain religious practice, but I had no idea about the story behind it. And during my fieldwork, I discovered these parallels between borsook in Kyrgyzstan and cooking pilaf on Thursday evenings in Uzbekistan.

Leyla: If you could just explain why people do it on Thursdays or Fridays. I’m curious to know because my mom also makes halvah on Thursdays.

Usmon: People recite the Koran and perform these practices on Thursday evenings because it is on Thursday evenings that the Islamic Friday starts. And Islamic Friday, Jumu’ah, is a special day for all Muslims because it’s the day when Muslims perform the weekly congregational prayer.

Because the Islamic calendar is lunar-based … Islamic Friday starts on the evening of Thursday, according to the Gregorian calendar. Basically, people recite the Koran and perform these rituals at the beginning of Friday. That is right at the time of the evening prayer, the Maghrib prayer.

Leyla: Now Uzbek pilaf as well as other variations of this dish are made from rice. Merry White earlier also mentioned the importance of rice in funeral rituals in Japan, so it seems like rice as a basic staple factors prominently in funeral food cultures across the world.

Eshe: We’ll hear more from Leyla after the break.

[break with SAPIENS ad]

Leyla: Candi Cann, who studies death, dying, and grief from comparative perspectives, writes about starch staples in the book called Dying to Eat: Cross-Cultural Perspectives on Food, Death, and the Afterlife. She says, “The consumption of starchy staples in funeral feasts and memorialization ceremonies is symbolic of their place in life. They are ubiquitous and universal; whether rice, wheat, or corn, these foods are literally the foods consumed to sustain life, and thus they are also the foods needed to sustain the dead in their afterlives.”

I’m now meeting with Joanna Davidson, professor of anthropology at Boston University. She has been studying the role of rice for the Jola community in Guinea-Bissau in West Africa. For this community, rice plays a crucial role in separating the living from the dead. Here’s what she has to say about rice for this community:

Joanna Davidson: There are particular kinds of foods that obviously have more coded meanings. In a Jola context, it’s not distinctive that rice shows up in funerals because rice is everywhere all the time. It is the staple that everybody spends most of their lives producing and consuming and, in some ways, bringing into ceremonial contexts. So every meal every day has rice, and sometimes just rice.

In a Jola religious worldview, there’s a contract that is at the basis of their understanding of the kind of relationship between the natural and the supernatural worlds. In a supernatural realm, the supreme deity, called Amitai, provides the rain. That is their job. They provide rain. And in the natural world, where humans and the natural forces live together, their end of the bargain is to do the work to cultivate rice. So a human by definition for the Jola—the way to be a full human person—is always tied up in some way with the production and consumption of rice. And so the living people at a funeral, in order not to be confused with the dead, adorn themselves [with], carry, and consume rice. Rice is everywhere at a funeral.

Leyla: Just as the Soviet government was interfering with the Muslim communities’ ability to perform their funeral rituals, the ability of the Jola in Guinea-Bissau to perform their traditional rituals faces an external challenge. This time, it’s climate change and its negative impact on their ability to produce enough rice. So a lot of changes and transformations are unfolding in response to this challenge.

Joanna: One of the ways that this is happening is that there’s become a separation between what’s used as ceremonially-OK rice—rice that you can use in a ceremonial context, like a funeral—and other rice that is now considered OK to just eat as a staple.

Leyla: And it’s often rice imported from elsewhere.

Joanna: There’s not enough rice that can be grown to nourish everybody. So more effort is going into doing the kinds of economic work needed to trade or to buy what Jola will call “sack rice.” Often that’s imported from countries that have much, much, much higher rates of production, so China, Vietnam, Thailand, India. Most of the rice that gets imported into West Africa is from those countries; Indonesia sometimes, too. And the local rice that’s grown is saved for the ceremony context, whether they’re funerals, whether they’re other kinds of shrine rituals, other kinds of things where it’s really necessary to have the local rice. I don’t know how long that will go on, but that’s where they’re at now, at least.

Leyla: I remember reading a while ago a book by philosopher Hans Ruin. It’s called Being With the Dead: Burial, Ancestral Politics, and the Roots of Historical Consciousness. And in that book, he says that death isn’t something that only belongs to the past, where the deceased are completely separated from the living. Instead, he says, it’s better to see death as a connection between those who have passed away and those who are still alive because in certain ways, we continue living alongside the dead. And that’s what “being historical” means.

Burials and funeral rituals are central to this relationship because these are ways of caring for the deceased, even after they’re gone. Funeral rituals aren’t just a formal way of disposing of bodies. Neither are they just about comforting the grieving or repairing society’s wounds, like classical anthropological accounts would suggest. Rather, it’s about acknowledging the connection with those who have passed, keeping their memory alive, and treating them with the respect they deserve. Funeral rituals encourage us to think deeply about the reality of death and our relationship with those who have died.

This brings us to the end of my journey toward a better understanding of the importance of funeral rituals. Now I can say that there is no rational explanation to my questions. What matters is the recognition of a profound sense of duty and obligation to care for our dead.

[Leyla’s mother praying]

I’m still with my mom in her kitchen, and she just finished preparing halvah. With a quiet sincerity, she says another prayer, asking Allah to accept this halvah as a tribute to the memory of the deceased and to grant mercy to their souls.

[Leyla’s mother praying]

[music]

Eshe: SAPIENS is produced by House of Pod. Cat Jaffee and Dennis Funk are our producers and program teachers. Dennis is also our audio editor and sound designer. Christine Weeber is our copy editor. Our executive producers are Cat Jaffee and Chip Colwell. This episode is part of the SAPIENS Public Scholars Training Fellowship program, which provides in-depth training for anthropologists in the craft of science communication and public scholarship.

SAPIENS is an editorially independent podcast funded this season by the John Templeton Foundation with the support of the University of Chicago Press and the Wenner-Gren Foundation. SAPIENS is part of the American Anthropological Association Podcast Library. Please visit SAPIENS.org to check out the additional resources in the show notes and to see all our great stories about everything human. I’m Eshe Lewis. Thank you for listening.