Can Child Sex Offenders Be Rehabilitated?

In the first season of Showtime’s Dexter, the character Dexter Morgan, a vigilante serial killer who also works for the fictitious Miami Metro police as a forensic technician, hunts a child molester who had escaped justice and the law. After nearly strangling his prey, Dexter yells, “Open your eyes and look at what you did!” The molester, a choir director who also murdered some of the young boys he assaulted, cries, “I couldn’t help myself. … Please, you have to understand.” Dexter replies, “Trust me, I definitely understand. See, I can’t help myself either. But children, I could never do that. … I have standards.”

The success of the series, which ran for eight seasons and attracted a record-breaking 2.6 million viewers for its season four finale, relied on an identification with Dexter, whose compulsive lust for murder was justified by his targeting of bad men. Both Dexter and his victim were obviously guilty, but only his victim—the child molester—was considered incorrigible. Dexter-the-serial-killer, it was hoped, might overcome his compulsion. But to even pose the question of change for child molesters seems an affront to society, as if it shows disrespect for the experience of the victims of such abuse. Yet the abhorrence that we as a society feel toward child molesters is part of the reason that molesters often don’t get the help they so desperately need.

In the last half-century in most of the Western world, the child molester has emerged as a new criminal type, a figure of abjection who evokes a visceral reaction of loathing and repulsion. It is common today to describe a child molester as the epitome of evil, a “sexual predator” outside the moral limits of what it means to be human. He shares with the Islamic terrorist the designation of a major security risk. Extraordinary legal doctrines enabling permanent preventive detention—imprisonment, continuous surveillance, forms of house arrest—are applied to both figures. Confounded by this evil, the public unites in a general sentiment that of all criminal types, the child molester is the least deserving of empathy—that he is unredeemable. In legal jargon, he risks becoming a recidivist, doomed to repeat his crime; in psychiatric jargon, he is cursed with a psychic disorder, a “paraphilia” (intense sexual arousal to atypical objects), that makes him virtually incapable of change.

But our beliefs about child sex offenders, as a whole, are rife with stereotypes that don’t hold up to expert scrutiny. One particular assumption still dominates our view: They are incapable of change, so they should be removed from the public sphere—either killed or made to endure lifelong punishment. While the judicial system does not typically handle most cases in one of these two ways, such thinking has pervaded our views. Yet incarceration alone does not serve society well, nor is it the most cost-effective or humane way to actually reduce child sex abuse.

This isn’t simply about recognizing the humanity of offenders: To foster environments where children are not abused, we must understand why adults abuse them. The inquiry itself is very unsettling; we often experience disgust when asked to examine these acts, these people, and these situations. Our discomfort and fear of incorrigibility are part of the problem: They are often based on a set of unconscious assumptions divorced from the circumstances surrounding child sex abuse. Our inability to question these assumptions makes it even more difficult to address the issues at hand.

In Europe, where for over 30 years I have engaged in research on a variety of topics, from kinship and national identity to retributive justice and the rehabilitation of child sex offenders, there is a greater emphasis on and investment in therapy for child sexual abusers than in the United States. In Germany, a 2002 federal law even mandates that individuals sentenced for sex abuse to more than two years of imprisonment have not only a duty but also a right to treatment.

In 2008, I began an ethnographic study of child sex offenders in Germany who were serving time and participating in therapy. I attended weekly psychodynamic group therapy for 35 men and boys between the ages of 13 and 62 accused or convicted of child sex abuse. In four modules, offenders explored the sequence of events leading to the act (often called “crime cycle”), empathy for the victim and apology, personal biography, and relapse prevention. I also worked in a minimum-security prison, where I examined approximately 200 cases of convicted child sex offenders from between 2001 and 2008 at the archives of the Berlin Senate Department of Justice. I followed offenders from the accusation of abuse to arrest, admission of culpability, trial, imprisonment, treatment, release from prison, and social reincorporation or indefinite surveillance. The results of my five-year study shed light on why some people offend, how therapy might redirect their lives, and the value of understanding both.

Contrary to popular understandings, our stereotypes of pedophiles are misleading when generalized to child sex offenders, who do not share a “sexual orientation” or “object choice” that would be comparable to “homosexual” and “heterosexual” orientations. They are not all men (although over 90 percent of those who are accused and arrested are men), and they are not all interested specifically in sex with children. The type of sexual predator portrayed in popular stories does indeed exist: Lawrence G. Nassar, for example, the longtime team doctor for USA Gymnastics, was recently found guilty of sexually abusing more than 150 women and girls over two decades. He was sentenced to 40 to 175 years in prison on top of 60 years for federal child pornography.

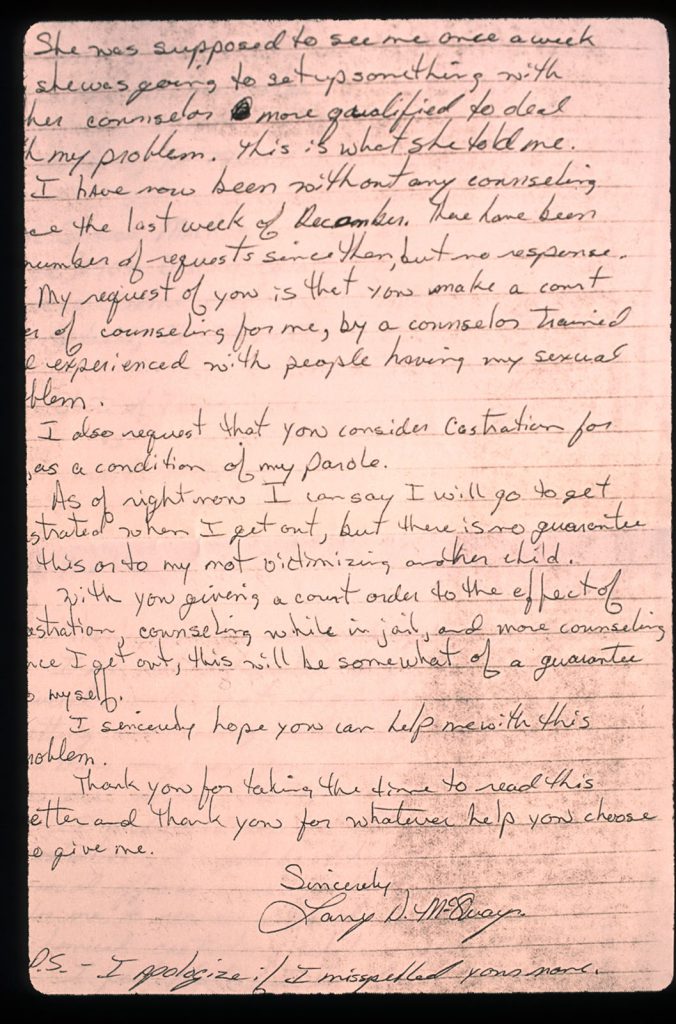

But most convicted child molesters are not in fact serial offenders. They have a low recidivism rate. When treated in prevention programs, they have a recidivism rate of 14 percent, which is lower than their untreated counterparts, who have a recidivism rate of 26 percent, according to a 1999 meta-analysis. Overall, treatment programs reduce the recidivism rate by up to 50 percent, according to a summary evaluation that compared over 20 studies. Saving even just one child from abuse makes the effort to offer therapy to all offenders worth it.

Furthermore, child sexual offenders often find themselves lumped together, despite the age of their victims, the severity of their crimes, and the duration of abuse. If treated, very few offenders become recidivists; the vast majority are not at risk of abusing additional children. Too often, however, policy prescriptions are made based on sensational cases, the least frequent type. High-risk offenders like Nassar present unusual problems, but should such exceptional cases be the basis for policies intended to address the majority of offenders?

The reasons why men seek out children and youth for sex are numerous, and they grow out of singular histories in which many have themselves suffered from neglect and abuse. In therapy, offenders often reveal motives not driven by a desire for sex but rather ones that emerge out of fears of abandonment, emotional loneliness, an inability to trust adults in intimate relations, low self-esteem, or an opportunism not available with adult partners. Sexual transgressions can easily tend in the direction of a fetish or a perverse and unconscious wish to harm the object of their desire. Yet, of the men I observed in therapy, interviewed, read files on, and consulted their therapists about, the most common motivation was neither to harm nor to have sex with the child. Rather, most men wanted intimacy with something more abstract, such as vulnerability, an image of innocence, or the ambiguity we associate with puberty.

These motivations in no way excuse abuse or lessen the damage to victims of abuse. But if the goal of imprisonment and treatment is to decrease the number of transgressions and bring about a change in the offender so as to eventually reincorporate him into society, then we have to understand and address the actual motivations for intimate transgressions, including sexual.

What, specifically, can therapy do? And what are its limits? To be sure, treatment cannot help all offenders, and some treatment methods are more effective than others. The same approaches are used throughout the Western world: single diagnostic sessions, chemical castration, psychopharmacological treatments, cognitive behavioral therapy, and psychodynamic approaches. Of the treatment options available, psychodynamic therapy has been shown to be the most cost-effective and efficacious. This form of talk therapy goes beyond impulse control, avowed renunciation, or the anesthetization of desire. Optimally, it facilitates a psychic change: a transformation in the emotions and unconscious thoughts driving someone’s actions. Psychodynamic therapy stands in contrast to cognitive behavioral therapy, the most commonly used treatment for child sex abuse, which attempts only to modify someone’s conscious, rational thoughts and behaviors. While the wrongness of the act is addressed, motivations for transgressive behavior are often left unexamined.

There are no typical cases of child abuse nor of the rehabilitation of offenders. But to illustrate, consider one from the 35 men and boys I followed in therapy. Uwe (a pseudonym), a 37-year-old man, was accused of incest with his 4 1/2-year-old daughter. Below is Uwe’s story, as he recounted it to therapists, who grilled him on the specifics, repetitively and painfully. I narrate a brief version of it here because, although terrible to hear and verifiable only through firsthand testimony, I think our disgust inhibits our ability to comprehend such acts and prevents us from dealing with the problem.

Uwe’s wife had recently left him and moved in with another woman, taking their two children with her. Uwe claims that his daughter began to play with herself in visits with him; Uwe was accused of participating.

Uwe never disputed the allegations his daughter or ex-wife made of these behaviors, or of his participation in them, but he was so alarmed by what he had done that he could not talk about it during the first four weeks of the group therapy to which he was assigned. He was a man of few words who appeared comfortable listening to the others; he talked only when called upon and then only in barely audible, mumbled phrases. The other men in the group were curious but also a bit angry at Uwe’s reticence, and they needled him until he reluctantly explained: “My daughter, who was 4 1/2, discovered that she could gratify herself. I helped her.”

The two therapists who conducted the group therapy sessions spent months asking why the daughter discovered masturbation at this point in her life and what role Uwe played in her discovery. The therapists’ eventual explanation, based on established psychological theory, was that the daughter had noticed the deep sadness of her father and sought to please him and regain his attentions through sexual play. (Of course, the child is not to blame in any way; it was Uwe’s reaction that bears the responsibility for his daughter’s behavior.) As Uwe justified it in his fifth month of therapy, he began to stroke her behind, legs, and feet “to take her mind off the vagina.” The end result, however, was that he played with her while she played with herself. (The daughter had entered separate therapy, and according to her therapist, she was doing well.) What he did was clearly child sex abuse: engaging in sexual behavior with a child.

Uwe’s problem was not the result of a mental error needing correction: He was quite cognizant of his transgressions, which is why he felt so guilty after he realized what he had done. Rather, his problem, the therapists concluded, was of not knowing how he was communicating his feelings of loneliness and abandonment to his daughter, which led him to indulge in an unconscious fantasy with her.

Once he was able to understand why he had encouraged his daughter to perform in front of him, Uwe was better able to accept what he had done and why he deserved to be punished. The judge terminated Uwe’s probation after he completed 30 weeks of therapy. His wife has moved to another city, and he no longer has contact with his children. The hope is that he will, at some point, develop healthier attachments and not be pulled back into the vortex of child sex abuse.

It is impossible to measure the extent of psychic change that therapy brings about. Such change is a matter of interpretation. But I can report that Uwe, and nearly all others in the therapy groups I followed for three years after the end of their formal therapy, did not reenter the system of reported abuse, accusation, and investigation. Some of the men I observed had already had access to cognitive behavioral therapy in prison. But they consistently claimed that they were only schooled in what they did wrong; they did not arrive at a better understanding of what they had done and why.

During psychodynamic therapy, in contrast, I observed men who, for the first time, developed the capacity to critically analyze and reflect on themselves and their history of relationships. Although most would insist throughout therapy that they strongly empathized with children, only with the introspection demanded by the therapists did they come to empathize with the specific child or children they had victimized. For Uwe, incarceration without a deeper understanding of who he was, and how he came to molest his daughter, likely would have been costly and useless.

Ultimately, it is judges who are given the most power in assessing whether—and what type of—therapy works. In Germany and elsewhere in the West, judges are more and more frequently demanding evidence not merely of a behavioral change but of a self-transformation in child sex offenders. They are asking for the kind of deeper evidence of psychic change that psychodynamic therapy can best provide.

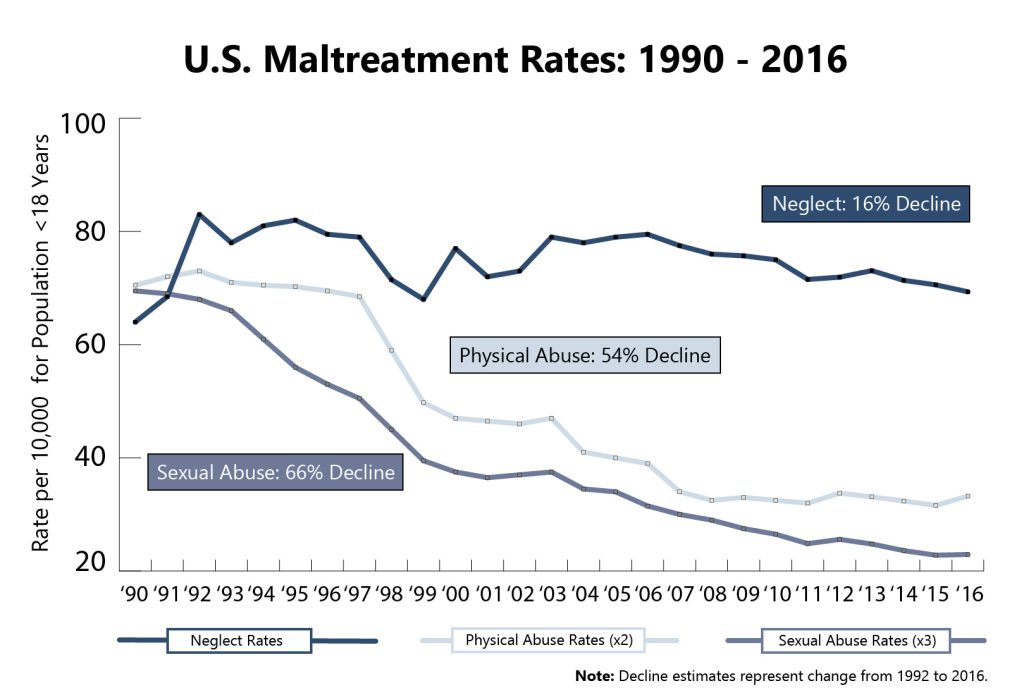

Even though many of the most extreme cases of abuse still go unreported, by all estimates the number of children who suffer sex abuse has declined over the past two and a half decades. The reasons for this are uncertain, but two important contributing factors are increases in prosecution and the rise of mandatory reporting by teachers and other care professionals of any suspect behavior. This probably reduces serial offenses and also creates a general culture of awareness that makes offenses less likely in the first place.

This is not without unintended effects, however. Opportunities for intimacy of any form between adult males and children have been severely restricted or highly sexualized—men are often driven away from caregiving professions out of fear that their actions might be misinterpreted, for instance. And innocent acts, such as putting a child on one’s lap, are often regarded as sexual. Sequestering children from the adult male population to prevent harm may yield a kind of security, but it hardly responds to the child’s need for touch, care, and attachment.

Further reductions in child sexual abuse, and the creation of caring environments of trust, require a more precise understanding both of child molesters and of our collective fears of their incorrigibility. Although the scientific community has repeatedly assessed assumptions about the unchangeability of child molesters and found them wanting, incorrigibility continually resurfaces as a convenient way to categorize and stereotype, without having to understand the multiple and often contradictory factors that make change appear impossible.

Are child sex abusers incorrigible? There is no evidence for such a general assumption. Like with all transgressions, there is no single motivation nor a uniform type of offender. Punishing child sex offenders through long-term incarceration neither rectifies the harm done to children nor creates the desired security for children. The best redress of this harm that also reduces recidivism, protecting the public from further criminal acts, is to try to rehabilitate the offenders through therapy.