Peeling Back the History of the Banana

This article was originally published at The Conversation and has been republished under Creative Commons.

In a globalized world, we routinely move enormous quantities of food around the planet in trade and for aid. Many countries, including the U.K., would struggle to feed their populations without food imports. Most people are used to being able to buy a wide range of produce that domestic farmers would struggle—or find impossible—to grow. A typical example is the banana, once a prized exotic novelty, but now a staple in many countries’ supermarkets.

Bananas are one of the most widely grown, traded, and eaten of all the crops—an essential and much-loved part of the diet for many people around the world. Modern bananas are sterile, containing only tiny residual seeds, so new banana plants are propagated from cuttings. The sterile domesticated banana is the result of ancient crossbreeding between wild species. In contrast, wild bananas are packed full of bullet-like seeds and contain very little edible fruit.

Wild bananas can be found in the wet, hot forests of New Guinea and South and Southeast Asia, but for many years the origin of domesticated bananas was a complete mystery. Finding ancient evidence for soft, sappy plants like bananas is extremely difficult at the best of times. The problem is worse in the tropical forests, because of the rapid decay of organic matter in the heat and humidity.

Microscopic evidence

The answer was to use phytoliths, a technique first experimentally used in the late 1950s and adopted by archaeologists in the 1970s. These are tiny, complex-shaped particles of silica laid down in plant cells. Silica is an extremely durable mineral, and silica phytoliths have been shown to survive for millions of years in suitable circumstances. Phytoliths have provided an exciting tool for archaeologists and paleobotanists exploring the origin and history of tropical plants. Some phytoliths of domesticated bananas are distinctive and therefore give us a tool to chart their appearance in ancient sediments.

We have known for some time that phytoliths of cultivated bananas appear at Kuk Swamp in Papua New Guinea around 6,800 years ago. But how they spread into the wider world has not been clear and has led to much debate. Later finds include those from Munsa, Uganda, 5,250 years ago, and Kot Diji in Pakistan, 4,250 years ago. But the status of these finds as domesticated bananas has been disputed.

We have been investigating ancient tropical forest use in Sri Lanka and Borneo for the best part of 20 years. Now, in Fahien Cave in Sri Lanka, in deposits about 6,000 years old, we have discovered phytoliths identical with those from cultivated bananas.

The first people for whom we have evidence arrived at Fahien Cave perhaps as early as 46,000 years ago and used it for shelter regularly but intermittently thereafter.

Phytolith evidence tells us that from the beginning they were eating and using a variety of wild plants, including breadfruit, durians, canarium nuts, species of palm and bamboo—and wild bananas. Even today, the leaves, flowers, fruits, stems, and rhizomes of the two wild banana species on Sri Lanka are still used. Ethnographic observations suggest uses as diverse as plates, food wrapping, medicines, stimulants, textiles, clothing, packaging, paper-making, crafts, ornaments, and also in ceremonial, magic, and ritual activities.

But after the earliest appearance of the phytoliths of domesticated bananas, about 6,000 years ago, we found that phytoliths of wild bananas declined sharply.

How did bananas reach Sri Lanka?

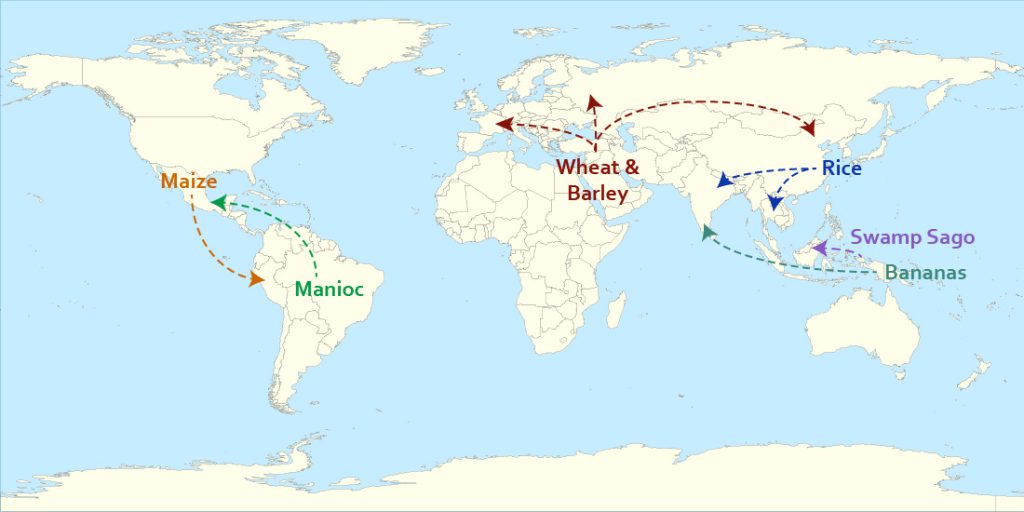

Less than 1,000 years separates the first certain appearance of phytoliths of cultivated bananas at Kuk Swamp, the earliest example of domesticated bananas anyone has discovered, and the first appearance of phytoliths of domesticated plants in Sri Lanka. Only dispersal by sea, carried perhaps by migrating people, is likely to have been rapid enough to bring domesticated bananas to Sri Lanka an estimated 800 years after their first certain appearance in Papua New Guinea. It is possible that they were then spread into South Asia and Africa from Sri Lanka, or that bananas reached them directly, during the same migration.

Ancient DNA studies suggest that movement of populations and interconnection between distant peoples in the ancient world was remarkably common. These early travelers seem, on several occasions, to have carried food plants with them, especially starchy staple crops. For instance, in an earlier paper, we suggested the carriage of swamp sago from New Guinea to Borneo about 10,000 years ago. This would have required a sea voyage of more than 2,000 kilometers, but the durable seeds of this important food plant could have been carried easily.

However, because domesticated bananas are sterile, reproduction has to be vegetative, so cuttings or whole plants must have been carried. The transport of banana plants or cuttings between Papua New Guinea and Sri Lanka would have been fraught with difficulty, as it most likely happened in open canoes—an amazing feat, even if the journey took many voyages over many years.

These heroic journeys also occurred on land. For instance Martin Jones’ Food Globalisation in Prehistory project has charted the spread of millet, wheat, and barley across Asia from the sixth millennium B.C. The ancient dispersal of manioc from central South America to Mexico and of maize in the opposite direction has also been suggested.

What does all this indicate? Global connections and exchange may be perceived as part of the modern world—but it is becoming increasingly apparent that these tendencies are deeply rooted in our prehistory.![]()