Bridging the American Cultural Divide

The Sufi mystics like to tell a story about an old man crossing a rickety footbridge that spans a deep gorge. When he reaches the wind-whipped middle of the bridge, he looks down and is filled with anxiety and fear. Behind him is his known and comfortable past. In front of him lies an uncertain future. Should he go back to what is familiar or move forward toward the unknown? Gradually, his fear dissipates, and he realizes that in order to continue on his journey he must cross the bridge.

In the United States, we have also reached the middle of a precarious footbridge. Can we move forward, or will we retreat?

The presidential election of 2020 threw a spotlight on a national cultural divide between Republicans and Democrats, between people who live in urban centers and those who live in rural areas, between scientific truth and conspiratorial fiction, between restrictive isolationists and global integrationists, and between tradition and change. There are profound differences in what Americans think about climate change, abortion, race relations, immigration—and the policy response to the pandemic.

The Pew Research Center—a nonprofit, nonpartisan fact tank based in Washington, D.C.—reported in November that the United States is exceptional in this divide. The gaping disparity between adherents of the two political parties has deep roots, this Pew article says:

“Supporters of Biden and Donald Trump believe the differences between them are about more than just politics and policies. A month before the election, roughly 8-in-10 registered voters in both camps said their differences with the other side were about core American values, and roughly 9-in-10—again in both camps—worried that a victory by the other would lead to ‘lasting harm’ to the United States.”

Many Americans today face unparalleled uncertainty about the future, with confusion and disagreement about how this fissure might be (or whether it should be) healed. Can we move forward to become a society that respects one another’s differences, or will we retreat into a society with entrenched and acrimonious divides?

I come to this question as an anthropologist who specializes in the study of religion, immigration, and politics. I teach cultural anthropology at a university in Pennsylvania—one of the most divided states in America, with a nearly 50-50 split in votes for presidential candidates Joe Biden and incumbent Donald Trump.

Over the course of my career, I have conducted extensive research in the Republic of Niger, where I spent a period of almost 20 years doing ethnographic fieldwork among the Songhay people. I have written about my experiences in several books, including In Sorcery’s Shadow (with co-author Cheryl Olkes) and Yaya’s Story.

As the narratives in those texts suggest, I have been particularly impressed by the resilience of the Songhay. They are a people who have lived for more than 1,000 years in the Sahel of West Africa: a dry, windswept, and desolate region on the southern fringe of the Sahara Desert. It is a starkly beautiful place that is prone to frequent droughts, famines, diseases, epidemics, and political instability. Although Songhay people may be materially poor, they are, I realized, rich in a wisdom that has enabled them to confront, with grit and grace, a long history of existential challenges.

When I talk with my students about the social dynamics of contemporary American society, we often consider a topic that Songhay elders like to discuss: the slow pace of cultural change.

When disruptive social events unfold—the loss of a job or a lease, a breakup or a decree of divorce, a climate disaster that forces relocation, a debilitating illness or death in the family—people are compelled to respond to a new set of challenges. These adaptations can be relatively fast. In the domain of culture, however, core beliefs about our kinship roles, religion, or political ideology develop and change at a much slower pace.

Despite the passage of centuries, some antiquated attitudes about gender persist.

The roots of mainstream American views of gender, for example, emerged in response to the socioeconomic demands of small-scaled agricultural societies in 18th-century Europe. The social mores of that time dictated the strict segregation of men’s and women’s labor, social activities, and expected behaviors. Despite the passage of centuries and the ongoing presence of feminist contributions to our cultural consciousness, some of these antiquated attitudes about gender, such as mainstream beliefs that devalue women’s work, persist in contemporary America.

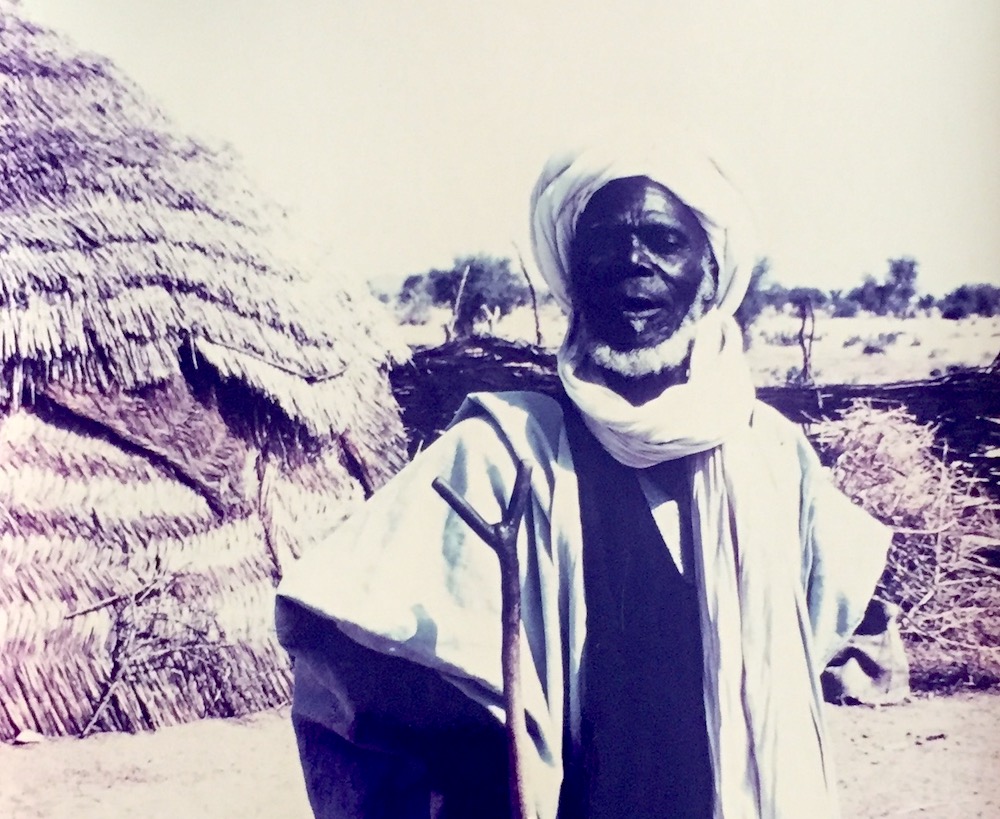

During my time with the Songhay, my teacher and mentor Adamu Jenitongo, a Songhay healer, patiently and gradually conveyed to me his insights about the human condition. Adamu Jenitongo understood that some things need to happen slowly. He liked to say: “Andurnya kala suuru.” (“Life is patience.”) Perseverance on the path of life can result in life’s greatest rewards.

According to Adamu Jenitongo, the mind slowly expands with experience. In particular, this means that elders are more capable of wisdom. In the Songhay culture, elders draw from the wisdom of their experience to guide young people.

I have gradually learned that it is usually good to pace myself and reflect. My students tell me that the pandemic has forced them to slow down and be more mindful. In these times of partial lockdowns, remote interactions, and physical distancing, many of them are finding the time to daydream, think, and ponder the future. It is also a time, I suggest to them, to find a mentor who can talk, listen, and guide them through this difficult time.

The resilience and hard work of my students has always filled me with hope for the future. Many of them are the first members of their families to attend college. They often come from families of modest means. Many of them have been working one or two jobs to pay for their education.

Despite these burdens, which eat up their time and sap their energy, they persevere. Given the privations of living through a painful pandemic, I am inspired that they are able to turn in stunningly original work.

Young Americans have reached the middle of the footbridge, an uncertain place of anxiety and social turbulence. The coming years and decades may be hard, as America struggles to slowly grow into a place of wisdom. It will take time. But I believe that the strength of our young and the wisdom of our elders will let us eventually cross the footbridge to a new, more unified society.