The Evolutionary Enigma of the Human Eyebrow

This article was originally published at The Conversation and has been republished under Creative Commons.

Eyebrows. We all have them, but what are they actually for? While eyebrows help to prevent debris, sweat, and water from falling into the eye socket, they serve another important function too—and it’s all to do with how they move and human connection.

We already know that our modern minds often reflect the ways our ancestors needed to work together to survive in the distant evolutionary past. But it seems our anatomy also reflects the importance of getting on with other people. As our new research published in Nature Ecology and Evolution suggests, the ability to look either intimidating or friendly is reflected in our bones—at least where the shape of the skull is concerned.

We all know that ancient species of humans, such as Neanderthals, looked a little bit different from us. But the most obvious difference is that archaic humans possessed a pronounced and very distinctive brow ridge, which contrasts with our own flat and vertical foreheads. And for scientists, this difference between us and them has been the hardest to explain. It was even famously said that Neanderthals would go unnoticed on a New York subway if only they could wear something like a hat to cover this distinctive feature.

But our latest research may have found an answer to explain why archaic humans had such a pronounced wedge of bone over their eyes (and why modern humans don’t). And it seems to be down to the fact that our highly movable eyebrows can be used to express a wide range of subtle emotions—which could have played a crucial role in human survival.

A sign of dominance

Research has already shown that humans today unconsciously raise their eyebrows briefly when they see someone at a distance to show we are not a threat. And we also lift our eyebrows to show sympathy with others—a tendency noticed by Charles Darwin in the 19th century.

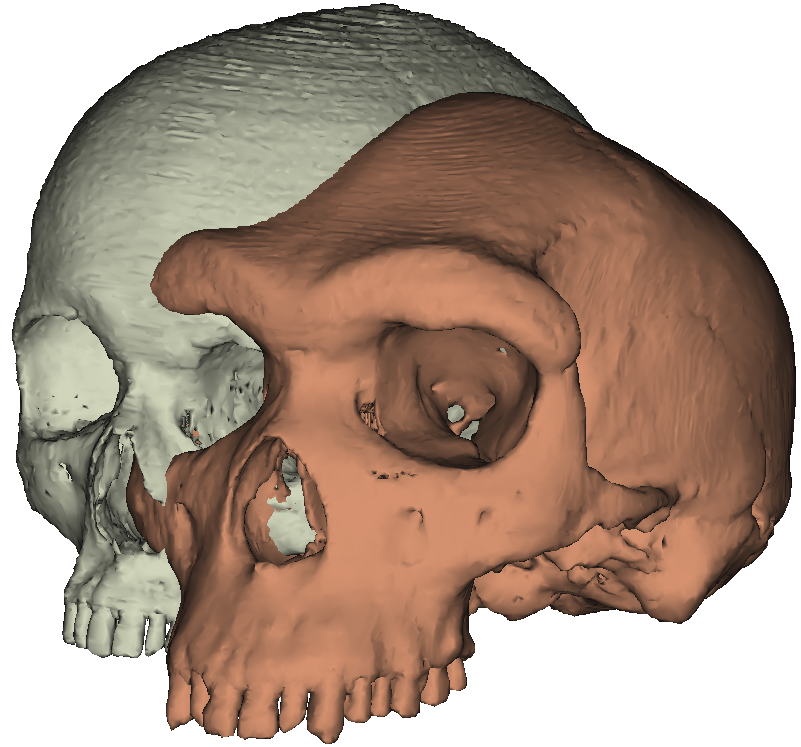

So my colleagues, Ricardo Godinho and Paul O’Higgins, and I looked at the iconic brow ridge of a fossilized skull (known as Kabwe 1) to find out more about its purpose. Godinho used 3D engineering software to shave back Kabwe’s huge brow ridge. And in doing so, he found that Kabwe 1’s heavy brow offered no spatial advantage.

The brow ridges in archaic humans also serve no obvious function in relation to chewing or other practical mechanics—a theory commonly put forward to explain protruding brow ridges. When the ridge was taken away, there was no effect on the rest of the face when biting. This means that brow ridges in archaic humans must have had a social function—most likely used to display social dominance, as is seen in other primates.

For our species, losing the brow ridge probably meant looking less intimidating, but by developing flatter and more vertical foreheads, our species could do something very unusual—move our eyebrows in all kinds of subtle and important ways.

Although the loss of the brow ridge may have initially been driven by changes in our brain or facial reduction, it subsequently allowed our eyebrows to make many different subtle and friendly gestures to people around us.

Expressing emotions

Historically speaking, these marked changes in the face occurred at a time when the emergence of important social changes began to take place—mainly, the collaboration between distantly related groups of humans.

This was a time when modern human groups began to exchange gifts across large regions. Being able to create distant friendships probably helped early humans to colonize new environments, as they had friends they could rely on and retreat back to.

Modern humans also lived in larger and more diverse groups than previous species, thereby reducing interbreeding. So the impacts of friendly and mutually supportive relationships with people outside one’s own group were far-reaching. And the development of mobile eyebrows may have been a key part of all these changes.

But these changes weren’t just exclusive to humans—the developments seen when wolves became domesticated are in some ways similar. Dogs have more waggy tails and flatter faces than wolves. And dogs who are better able to look cuter by raising their brows are more likely to be selected from shelters.

It seems, then, that for humans (and dogs) being able to get along with others was key to survival. And for our ancestors, the evolution of the eyebrows performed an important function in expressing friendliness. All of which forms part of a process of “self-domestication”—where our human brains, bodies, and even anatomy reflect a drive to get on better with those around us.![]()