Digging Up Woodstock

On a cloudy morning in October 2017, I found myself on a hillside in Bethel, New York, thinking about the most efficient way to remove leaves that covered the hill’s rocky surface. Below the wooded hill was the open, grassy field where, 50 years ago, around half a million young people came together for “three days of peace and music” in one of the defining events of their generation.

I and several other archaeologists from the Public Archaeology Facility (PAF) at Binghamton University in New York were beginning a project at the site of the Woodstock Music and Art Fair. Our team was there at the request of the Museum at Bethel Woods, which was established in 2008 as custodian of the 1969 Woodstock festival site. The museum focuses on preserving and interpreting the legacy of the ’60s and the spirit of the festival.

Archaeology—surprisingly, to some—has played a small but vital role in these efforts.

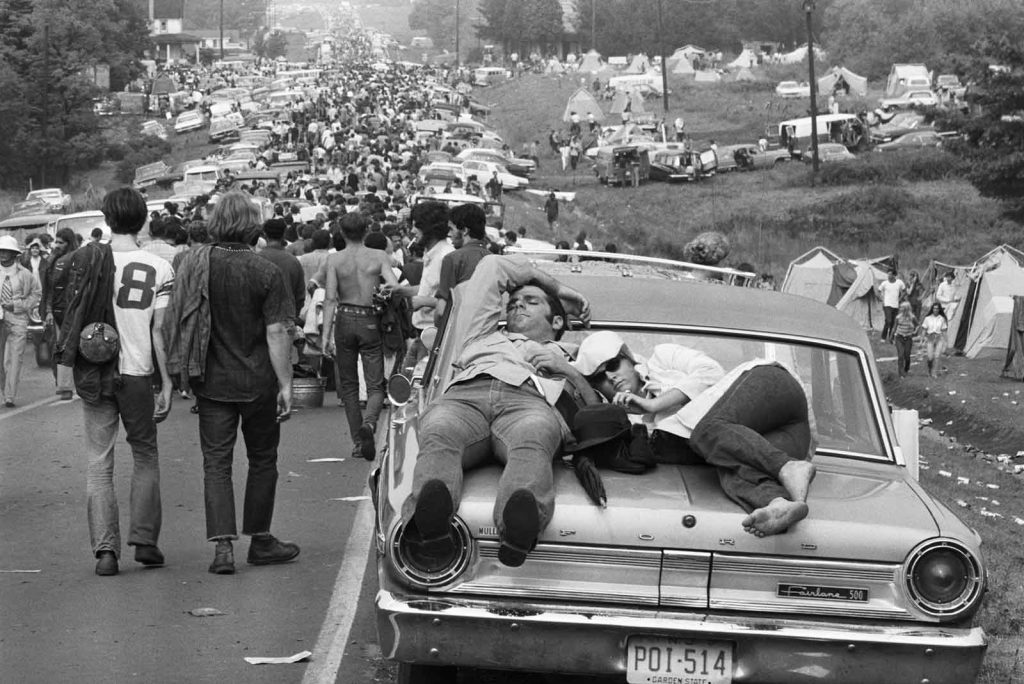

For most people, the term archaeology conjures images of dusty dig sites and ancient artifacts, not a music festival that occurred within recent memory on a farm in upstate New York. The question I have answered most frequently about the Woodstock project—“Why do archaeology at Woodstock?”—generally expresses both confusion and interest in our research. The study of the recent past by archaeologists perplexes many people. They do not understand why we would be interested in Woodstock or what we could add to all the many photos, media reports, and stories from people who were there.

But the museum staff was innovative enough to consider that archaeology could answer certain questions. The concert itself is infamous for being messy and disorganized: The organizers of the festival stopped bothering to collect tickets after the fences came down, and the crowd grew to many times what they were expecting or able to handle. Amid the chaos, no one paid attention to the exact position of the stage or vendor locations. At the best of times, people’s memories are faulty; for drug-fueled Woodstock, one of the common jokes is that if you remember it, you weren’t there. Archaeology can help to fill in these gaps.

Our results have been mixed: not everything has been made clearer and not all the questions have been answered. But archaeology at Woodstock has produced new evidence that has aided the Museum at Bethel Woods in their mission to interpret and preserve the site, and has opened a conversation about the site’s past and future.

When the Museum at Bethel Woods contacted us about doing archaeology at the site in 2017, our primary concern was not whether archaeology was applicable to such a recent context but whether we would find enough material evidence for viable interpretations. Festivals are relatively short-lived phenomena, and typically, facilities are not substantial constructions. Woodstock, in particular, was organized on counterculture principles aimed at minimizing the festival’s impact on the landscape. This ephemeral nature makes it difficult to identify artifacts or features, such as evidence of the concert stage. (Other researchers have had similar issues doing festival archaeology at, for example, the Burning Man site in Nevada.)

Before Woodstock, the site was part of dairy farmer Max Yasgur’s land, and it returned to this use within weeks. How could we associate a tin can fragment, glass shard, or drink container pull top with the festival rather than daily activities on Yasgur’s farm? How could we reconstruct what happened on the site over three days (and a little more than a month of preparation and cleanup), when most of the facilities and trash were removed? Ephemeral activities and sites, such as Woodstock, pose some of the most difficult methodological and interpretive issues for archaeologists.

Portions of the Bindy Bazaar—an attraction within the heart of the festival—were not well-documented during the 1969 festival. The bazaar held an “Indian Pavilion,” a playground, health and safety services, parking in the open field areas, and a specific area for vendors and informal trading on a wooded hillside. The Museum at Bethel Woods’ plans included reconstructing the original trail network with interpretive signage within this wooded vendor area. We began our research there on that October morning, feeling a bit overwhelmed: We had two days to find and map some very ephemeral vendor booths.

The few existing photographs indicate that people constructed some makeshift vendor booths out of rocks, trees, boards, and other available material. After nearly 50 years, only the patterning of the rocks, aligned or clustered together, would still be present. To locate any traces of the vendor booths, our crew of six removed the leaves that obscured the hill surface using rakes and leaf blowers, and we systematically surveyed the hill to find and mark all potential rock patterns.

By the end of our two-day survey of the Bindy Bazaar, we had mapped and recorded 25 potential vendor booths and 13 other possible cultural features, including three small rock rings that were likely fire pits. (We had no particular reason to date them to the festival.) It was not always easy to determine if some of the more ephemeral rock arrangements were vendor booths. Others were obvious: arrangements in straight lines, rectangles, and other shapes.

A map created prior to the festival shows the general layout of the trails through the bazaar and the planned locations of 24 vendor booths (along with an illustration of a large turtle and other groovy, abstract drawings in true Woodstock style). In reality, our archaeological survey showed that the booths were clustered together on the eastern side of the hill, near trails leading to major festival areas. It is likely that vendors in the Bindy Bazaar had to sort themselves out without direction and not following existing plans.

The other priority for the Museum at Bethel Woods was identifying the specific physical locations of the 1969 concert facilities, which were taken down and recycled after the festival. As is shown in many photographs, the stage area was located at the base of a bowl-shaped hill flanked by speaker towers. Performers’ facilities were on the opposite side of West Shore Road from the stage; musicians crossed over via a temporary wooden bridge.

Memories of the festival, often recorded years or decades after, are filtered through a lens of interpretation.

Some disturbances were easy to see as our team walked over the former concert area. The most significant was a change in the hill gradient, indicating that the main stage area had been filled in since 1969. The work had likely buried any evidence that might have been there. This led us to focus on trash.

Logically, more trash would have accumulated in the more crowded areas; we thought that if we could find a pattern, it would help us relocate some of the concert facilities. We used a metal detector. There wasn’t a very clear pattern in the trash we found, but the tool did help us decide where to dig for further information. In one spot, we found, nearly 2 feet below the top of the ground, a soil stain that was left by a post—probably from the chain-link fence that cordoned off the stage area.

Signs of a post, rock features on a hill, and points of metal trash in a field: These all seem pretty mundane in the face of the wild images from Woodstock. These are, however, examples of the everyday aspects of activities and the organization of the material world that few other sources of information record.

Photographs from the event largely captured the performers or images of hippie culture. Memories of the festival, often recorded years or decades after, are filtered through a lens of interpretation. Archaeology adds something unique to the picture.

In the last several decades, concepts of what constitutes heritage have broadened to include popular youth culture sites, such as Woodstock: Woodstock was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2017. The Museum at Bethel Woods has museum displays about the culture of the ’60s and the Woodstock festival. This year, with our help and for the festival’s 50th anniversary, the staff began to reconstruct the trail network, with interpretive signage through the Bindy Bazaar. The wooded hillside is becoming a place that people can visit to reflect on the experience and memories of the festival, the meaning of the ’60s, or the beauty of the natural surroundings.

Woodstock has been, and will continue to be, many things to different people and audiences. As its history is continually re-recorded, re-interpreted, and represented, archaeology will play a role in how we continue to view the icons of the ’60s counterculture.