Finding and Losing the World’s Oldest Art in Sulawesi

In 2019, I made a trip to Sulawesi, one of the largest islands in Indonesia, to visit some of the world’s oldest cave art. So strong were my emotions that, in the visitors’ book of the cave of Leang Timpuseng, I wrote alongside the other lucky archaeologists and tourists who have been granted access: “and now I can die.”

The trip marked an emotional return to a part of the world I had visited nearly 40 years earlier on an anthropological expedition. It brought me full circle. Back in 1985, my colleagues and I documented a series of paintings in a cave just a few tens of kilometers away from Leang Timpuseng, long before anyone knew that some of the artwork in this region is so spectacularly old. In recent years, paintings from one of these limestone caves were dated to more than 45,500 years ago—the oldest cave art ever found.

Sadly, the specific cave we had visited—Sumpang Bita—was, within a year or so of our visit, subjected to well-intentioned but unfortunate restoration efforts that repainted over an image to make it clearer. In light of recent discoveries, the photos from our original trip have proven very useful to researchers, not only by showing the original state of the artwork, but also by helping to show how quickly paintings in this region are degrading.

Sulawesi, once DESCRIBED by the playwright Louis Nowra as “an octopus caught in an electric blender,” emerges rugged from the sea. To the adventurous eyes of my teenage self, pouring over the pages of an atlas from my home in Italy, Sulawesi looked like a jellyfish desperately swimming to Borneo to escape the New Guinean turtle’s greedy maw. I nurtured the hope of getting to Sulawesi one day. So, in 1985, when I was invited as an anthropologist to join an expedition designed to inspect the island’s southern caves, I accepted immediately.

It was one of the most intense and interesting journeys I have ever made, and I still have a vivid memory of it. Sometimes, I still see in my dreams the huge, brightly flamboyant butterflies of Bantimurung, where we had our base.

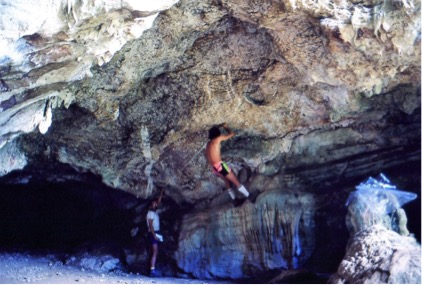

The landscape of southern Sulawesi is a jagged limestone karst potted with sinkholes: the remains of an ancient coral reef that emerged from the sea and was shaped by the tantrums of the region’s monsoons. After visiting and exploring various caves, one day we were told of a cave with paintings. At the time, I had never heard of cave art in those lands (although cave paintings had been found in this region since the 1950s, the reports were fragmentary and incomplete). Intrigued, I willingly joined my speleologist friends the day they decided to visit it.

To access it, we had to first navigate rice fields, walking on raised paths of slippery green rice seedlings surrounded by water. We were delighted by the myriad sounds of chirping birds and humming insects, and sometimes overwhelmed by the hammering cock-a-doodle-doo of a rooster who wanted to emphasize his male primacy to the rustic rabble. The straight flight of dragonflies and the ramshackle meanderings of butterflies distracted us, putting me at risk of getting bogged down in the paddy. Once past the flat ground, a half hour’s climb began. We stopped occasionally for water and to gaze at the surrounding landscape. Mixed with the chirping of cicadas were the sometimes awkward, often monotonous, and rarely melodic calls of exotic birds cavorting between the karst’s pinnacles.

When we reached Sumpang Bita Cave, we found it to be small and open, only 24 meters deep (a little less than the distance between bases on a baseball field). The artwork was easy to find on almost every part of the walls. For the speleologists in our group, the cave was too simple to be interesting for exploration. But I was completely enraptured by the paintings—including dozens of handprints, we counted more than 80.

There were depictions of an anoa, a small buffalo endemic to the island, and many warty pigs, medium-sized, greyish-black swine that still today move around in small groups. There was a drawing that we interpreted to be a boat, which was probably a more recent addition. I obliged the reluctant speleologists to find, photograph, and measure every detail in the cave. We collected meters of plastic sheets in the nearest village to make tracings.

We reported the findings in an Italian speleological publication. At the time, researchers were interested in elucidating the meaning of rock art: Was it art for art’s sake or an appeasement for animals killed in hunting? Did the images together depict a social allegory or was each one a separate expression? There was no reliable way to date such art at the time; the paintings in Sulawesi were generally assumed to be younger than 10,000 years old.

I was much more interested in what the handprints might reveal about handedness. I checked thousands of Italian junior high school students to assess today’s rates of left- and right-handedness to compare with those of our ancestors as recorded on the cave walls. The prints were “negatives,” whereby someone sprays colored water by mouth over a hand pressed against the wall. The dominant hand is thought to hold the bottle of colored solution (generally ochre, or sometimes hematite or gypsum, in water). With this assumption, I could collect information about the handedness of the people who decorated this cave in the past; there were more left-handers back then, it seems, than today.

For a while after that study, I largely forgot about Sumpang Bita Cave, overwhelmed as I was with other academic issues and efforts.

Then, in October 2014, researchers reported a thrilling find. Maxime Aubert, an archaeologist from Griffith University in Queensland, Australia, and colleagues had used a novel technique to date a painting of a babirusa (a pig-deer) in Leang Timpuseng Cave—not far from Sumpang Bita Cave—to at least 35,400 years ago.

The new technique was uranium-thorium dating of “cave popcorn.” These are small, round mineral deposits that form very slowly, layer after layer, from the evaporation of percolating water in limestone caves. The minerals contain tiny traces of natural uranium and thorium. Since radioactive uranium decays to thorium over time, the ratio of these two elements reveals the deposit’s age—the higher the proportion of thorium, the older the sample. The researchers took samples of popcorn from the paintings and ground them up for analysis. They were astonished by the results.

Being in the presence of such old palm prints was like witnessing a birth; I was overwhelmed by emotion.

Archaeologists had long been puzzled by the fact that cave art seemingly appeared in Europe around 35,000–40,000 years ago, when paintings, drawings, or engravings were scarce or absent elsewhere. With the new Sulawesi finds, it was demonstrated that rock art was produced in at least one other part of the world that long ago. This had implications for everything from the origins of art, religion, and human spirituality to the movement of Austronesian peoples. Many scholars consider these artistic activities to be the expression of a leap in human cognitive development. The issues are complicated and debated.

After that 2014 discovery, more came in quick succession. In 2019, Aubert and colleagues reported a figurative painting of a warty pig in another cave called Leang Bulu’ Sipong 4 to be at least 43,900 years old. The newest find, reported in January 2021, is particularly exciting. In the karst of Maros-Pangkep, two figurative paintings representing warty pigs were dated: One, in Leang Tedongnge Cave, was found to be at least 45,500 years old, making it—for now—the oldest-known representational painting of an animal in the world.

Sulawesi, not Europe, holds the oldest surviving cave paintings of animals.

Interestingly, in the cave art found in Leang Bulu’ Sipong 4, there were scenes representing figures that were part human and part beast (“therianthropes,” from the Greek for beast, “therion,” and human, “anthropos”). Perhaps this was the first human representation showing something imaginary—something that did not exist in the natural world.

In 2019, in the spirit of sentimental archaeology, I decided to go back to Sulawesi.

The privilege of being back on the south coast of Sulawesi filled my soul. As I walked through the karst hillocks (sometimes called mogote), the jagged forms had a dynamism that made me forget they were just rocks. Occasionally, ravines opened up, sparkling in the scorching sunlight, reminding me of the power of water in this landscape. The caves were furnished with stalactites and stalagmites: shapes that resembled curtains, skulls, jellyfish, frozen waterfalls, and bizarre chandeliers.

Some of the caves featuring artwork are now protected in a cultural prehistoric park and in a national park. I went first to Leang Timpuseng. Here and there, I could see the popcorn on the walls that had been used to establish the astonishing age of the artwork. Being in the presence of such old palm prints was like witnessing a birth; I was overwhelmed by emotion. The ancient person who put their hand signature on that cave wall would never have imagined that it would, thousands of years later, provoke such violent feelings, heartfelt debates, and global attention.

There were about 1,000 stairs to climb to reach Sumpang Bita. When I finally arrived, I did not really experience any particular emotion, perhaps I was overwhelmed by heat and fatigue. But there was a cold anger in me, too, knowing that some parts of the cave, shortly after our detection, had been treated with chemical solutions and touched up, and some surface minerals were removed. Such conservation techniques were used with good intentions, and the global significance of the images in this region was unknown at the time. However, the interventions might prevent some future attempts at dating.

The Indonesian archaeologist who accompanied me explained that the same fate fortunately only affected one other cave in the karst before the authorities became aware of the treasure that those mountains contained. Their thinking about appropriate conservation strategies has since changed. The archaeologist was overjoyed because we had photos of the original paintings. It seems that no one had formally documented the artwork before the conservation efforts.

The cave paintings in this region are today degrading quickly as the inside surfaces of the caves peel away. No one knows exactly why—perhaps it is air pollution from nearby motor vehicles and mining activities. Perhaps climate change is increasing humidity in the region, promoting mold or other microorganisms that eat away at the walls. Our photos could help scholars evaluate the speed at which these artifacts are degrading.

This amazing heritage is probably doomed to disappear, or at least be reduced. At least researchers are now diligently photographing and scanning the art. Without it we would not be able to see back to the dawn of human culture.