Hobby Lobby’s Antiquities Trouble

Indiana Jones would be annoyed. He had to fight snakes, Nazis, and booby traps to get the biblical artifact he wanted. But as a complaint filed July 5 by the United States Department of Justice shows, now you can just order ancient treasures to be delivered to your office via FedEx. That’s what Steve Green, president of the arts and crafts company Hobby Lobby, did. Starting in 2010, he purchased over 5,500 tablets and seals made thousands of years ago in what is now Iraq, intending to display them in his Museum of the Bible, set to open next year in Washington, D.C.

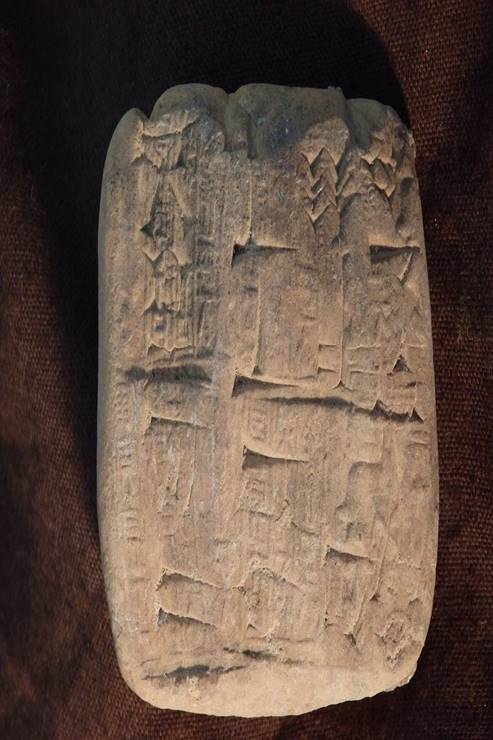

These antiquities were probably stolen from archaeological sites in Iraq, which continue to be heavily looted thanks to the ongoing turmoil in the country. Green’s artifacts are being seized because they were imported with false customs declarations: ancient clay tablets from Iraq became modern “sample” tiles from Turkey. Even if the customs declarations had been correct, importing stolen Iraqi antiquities into the United States has been illegal at least since 2008.

But these laws have rarely been used. The Hobby Lobby case is one of the few times that the U.S. government has seized illicit antiquities from a collector, and one of the very few times that the government has begun an investigation into smuggled antiquities without an initiating complaint by the country of origin. The Hobby Lobby case is also one of a surprising number of recent investigations by the U.S. government into stolen and smuggled antiquities.

Why the new crackdown on collecting? The answer is terrorism. In 2015, the government began warning U.S. buyers that their purchases of shady antiquities from the Middle East might help support terrorist organizations, such as the Islamic State, which often loot and sell antiquities from conquered territories.

It is extraordinarily difficult, however, for law enforcement to prove that the sale of any particular antiquity that ends up in the United States supported terrorism. Consequently, the government’s current strategy seems to be to make it difficult to sell any antiquities from Iraq or other countries that terrorists are looting, such as Syria, even if the known transactions have no obvious connection with terrorism. In one ongoing investigation, antiquities from Syria were seized from dealers who provided paperwork showing a legal history of export. Previously, authorities would probably have accepted these papers without question; now, dealers face the prospect of expensive investigations into transactions that were previously routine.

Archaeologists applaud such investigations, knowing that looted antiquities often appear on the legal market with false paperwork (especially in Israel, home of Green’s main dealers). But there will likely be a backlash from dealers and collectors, who have long disputed that many illicit antiquities make it to the U.S. market.

Maybe it’s time to think differently. Green wants the Museum of the Bible to tell a story about biblical history to its visitors. The ancient Iraqi tablets and seals he purchased could help tell this story, since they were created during Old Testament times. But every looted artifact on display in a museum means the loss of untold other aspects of the past, thanks to the inevitable destruction of archaeological information during snatch-and-grab illegal digging. And, although as an ancient art historian it pains me to admit it, these tablets and seals typically aren’t much to look at.

Instead of destroying the past to fill museum cases with objects for which most visitors won’t spare a glance, let’s change our ideas about what belongs in a museum. High-quality digital scans and 3-D printing technology mean that museums can share informative and inspiring objects from their respective collections without having to turn to a market of potentially looted antiquities. And Indy won’t even have to unfurl his whip.