When Women Say “Ta-Ta” to Ta-Tas

“I’ve decided to go flat.”

I said these words aloud for the first time to my surgeon. He was calling to check in on me the day after he delivered his recommendation of a double mastectomy. As a 44-year-old woman with a single 1.2-centimeter tumor and no family history of breast cancer, I had initially been told to expect a simple lumpectomy with no additional treatment necessary. Further testing indicated a genetic predisposition, and that had modified the risk analysis.

When delivering the change of plans, the surgeon was quick to add in an apologetic tone that spacers could not be placed at the time of surgery. He offered an explanation that I half listened to about skin tightening and risk of infection during radiation. I knitted my eyebrows in concern and nodded into the phone. While I had no idea what “spacers” were, the surgeon’s tone made clear that I was expected to be upset that I would have to wait for them.

Hydrogel spacers, also known as tissue expanders, it turns out, are temporary breast implants routinely inserted into the chest following a mastectomy. They are used to stretch the remaining skin and tissue in preparation for permanent breast reconstruction. A valve allows for the slow addition of saline, creating and strengthening a skin envelope into which a permanent implant can be inserted. Without spacers, remaining skin and fatty tissues are left flaccid until reconstruction can be performed.

The American Society of Plastic Surgeons touts breast reconstruction as important for the post-mastectomy patient’s “improvement in body image” and for their “sexual functioning.” Since 1998, insurance providers in the U.S. have been mandated by the Women’s Health and Cancer Rights Act (WHCRA) to offer reconstruction any time a mastectomy is covered. Whether immediate or delayed, breast reconstruction is now typically presented to women undergoing mastectomy as the routine next step.

Because my specific medical circumstances meant I had to wait, I received a prescription for camisoles with padded breast inserts. The insurance care navigator who signed me up for this benefit explained that it was so I could “feel normal when leaving the house” until I was able to proceed with reconstruction. After my surgical wounds healed, I would also be provided with medically issued bras equipped with insertable silicone prosthetic breasts.

“You want to go with the flap? OK. You can discuss that with a plastic surgeon after radiation is complete.”

That’s how my surgeon responded when I told him I’d decided to “go flat”—increasingly common lingo for opting out of breast reconstruction in favor of an intentionally smooth chest contour. Medically termed aesthetic flat closure (AFC), going flat entails tightening and smoothing the post-surgical chest wall. But instead of hearing “flat,” the surgeon thought I had decided on “flap” (or autologous) reconstruction. This is one of the two most common ways of creating breast mounds following a mastectomy. Flap surgery involves relocating skin, fat, and sometimes muscle from another part of the body to the chest. The method is touted as providing a more natural look and feel than “alloplastic” reconstruction (using nonbiological materials, such as silicone gel implants).

Dazed by the diagnosis of cancer and unaware of the choices and risks, many women seem to accept that breast reconstruction is just “what you do.” But, nearly half of women who have undergone the procedure are disappointed with the results. Aesthetic concerns include asymmetry, prominent scarring, rippling, and tissue necrosis. Where nipples cannot be salvaged, the patient faces an additional devil’s choice of no nipples or permanently erect replacements. Reconstruction can also lead to harmful, painful physical effects caused by rupture, leakage, capsular contracture (scar tissue squeezing the implant), infection, and wound reopening. Reconstructed breasts also typically lack sensation; as my sister-in-law says of her post-mastectomy chest reconstruction, “You could light these things on fire, and I wouldn’t even know.”

In short, breast reconstruction is not breast augmentation. And while breast reconstruction helps many women regain a sense of self following a mastectomy, it is not always a clearly informed choice.

“Well, you can always change your mind later.”

My surgeon was in disbelief when I told him that he had mistaken “flat” for “flap.” He told me I was only his second patient in a long and storied career who had requested flat closure, and that most women are “more interested in talking about the free boob job than they are about the cancer.” He chuckled to himself and then reminded me that the option of reconstruction would always be on the table.

The surgeon was not alone in his surprise at my decision. After a post-mastectomy fashion show for one in front of my closet mirror, I offered a friend the dresses I’d removed from my wardrobe. She responded, confused, “But you can still wear them after your reconstruction?”

Other women contemplating flat closure commonly report family and friends expressing concern they will not feel feminine without breasts, or that if left flat, their chest will be a constant reminder of the cancer. The pressure for reconstruction seems to be especially strong for younger women, an increasing percentage of the breast cancer community. Many, like I did, hear the refrain, “But, what will your husband think?” Or, if unattached, “But how will you find a partner?” In other words, if you don’t have breasts, you are unlovable. Or at least unfuckable.

Robust statistics are absent on the question of “flatties,” or women who choose to go flat. But somewhere between 19 percent and 58 percent of women do not pursue breast reconstruction following a double (DMX) or single mastectomy (SMX). The flattie community also includes those who “explant,” or have their implants removed, following reconstruction. Some flatties “live flat” while others always or sometimes “foob,” or use external prostheses (foobs are fake boobs) such as Athleta Empower Pads or Knitted Knockers to achieve a classic female silhouette. Studies suggest that those who go flat are, overall, satisfied with their choice.

“It will flatten over time.”

The “going flat” movement has been around since at least 2011, and it gained significant steam with a New York Times exposé in 2016. Still, declining reconstruction in a social milieu where it is not the norm can be a difficult choice. It is made even harder when a woman cannot find a surgeon to perform her desired chest contouring. The nonprofit organization Not Putting on a Shirt uses the term “flat denial” to describe situations where a patient requests a flat closure, but one is not provided.

At times, the issue is one of paperwork or policy. There is no standard medical billing code for flat closure in the U.S., and ambiguities in the WHCRA were long used by some insurers to categorize flat closure as an elective surgery (in contrast to the “medical necessity” of breast reconstruction). Patient advocacy led to the issuance of revised guidance for the WHCRA (and the Affordable Care Act) in 2024 to specify that AFC is a covered type of chest wall reconstruction. Some insurers and doctors have been slow to update their advising and billing practices.

Women deserve to decide what to do with their bodies.

In other cases, a surgeon disregards the patient’s wishes for AFC and leaves behind the extra skin and tissue that aids with reconstruction, just in case the patient later changes her mind. Other times, patients face flat denialism as the result of incompetency—a surgeon untrained or unpracticed in flat closure and unwilling to learn techniques to achieve a smooth contour.

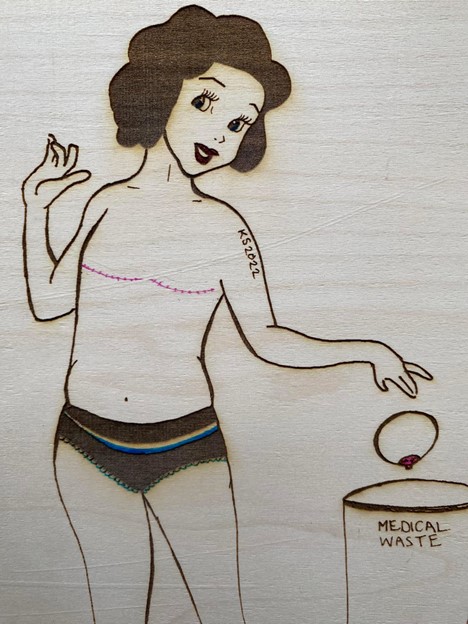

This is what happened to me. Like many women facing flat denial from their medical providers, the scar lines from my mastectomy were riddled with unnatural peaks, valleys, wrinkles, divots, puckers, and folds, along with underarm protrusions of skin known as “dog ears.” The mess made it difficult to look in the mirror. My body did not feel like it was my own.

When I expressed displeasure with his work, the surgeon dismissed my concerns. He told me, “It’s just swollen from the surgery. It will flatten over time.” He refused to consider a revision, seeming to imply that because I had opted out of breast implants, I was not entitled to an aesthetic preference. I could either have breasts akin to a blow-up doll’s or a secondhand beanbag chair—nothing in between.

“Can I get a second opinion?”

After some encouragement from my sister, a nurse, I asked the care navigator for an appointment with another surgeon to get a second opinion. After some hesitation and being sure to tell me that the doctor who had performed my original surgery was highly revered, she complied. The new doctor quickly scheduled a revision surgery to address not only the issue of flat closure but also the residual cancer cells that the first doctor had deemed inconsequential.

A cancer survivor can never be certain that they are 100 percent cancer free. But four rounds of chemotherapy and 25 sessions of radiation later, tests show that I have no remaining evidence of disease. It has been nearly a year since this journey began. I’ve lost my hair, I’ve lost my breasts, my bone density has weakened, and my lymphatic system will be forever compromised. I will need to take daily medications and receive monthly injections for another decade to reduce the chance of recurrence. But I am alive.

As I look back, I find myself, forever the anthropologist, interrogating the navigation of my own mastectomy alongside those of other women as a collective cultural artifact. In other words, while my cancer journey is personal and unique, it is also rooted in taken-for-granted societal norms that guide our standards, ideals, and expectations. A standard of care that calls for replacing breasts with stiff and senseless fabrications without mammary functioning both reflects and is rooted within an asymmetrical binary whereby a woman’s value depends in large part on her objectification. Breast reconstruction, in other words, has become so routine that it is easy to miss the ways it is rooted in patriarchy.

One way to show the women in your life that you value them as whole beings is to encourage them to schedule annual mammograms—not just to “save the boobies” but to save lives. While the imaging procedure does not detect all breast cancers, it does catch many. With 1 in 8 women estimated to develop breast cancer in their lifetime, the more cases that are caught early the fewer women we will lose to the disease.

Breast reconstruction will certainly continue to be an important part of recovery for many of these breast cancer survivors. But not for everyone. Rather than be prescribed our preferred chest contouring, women deserve to decide what to do with their bodies. And we all deserve to live in a world where there is room for women without breasts.