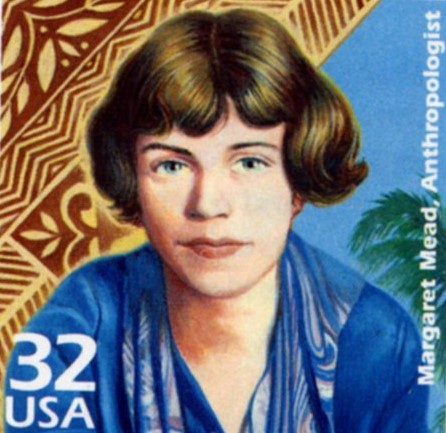

In January 1983, the front page of The New York Times read: “New Samoa Book Challenges Margaret Mead’s Conclusions.”

Anthropologist Derek Freeman had been building his critique of Mead for years, sending her letters and even confronting her in person. Freeman’s resulting book, Margaret Mead and Samoa: The Making and Unmaking of an Anthropological Myth, was published five years after Mead died.

Who was Freeman, and why did he take such issue with Mead’s work in American Samoa?

See the companion teaching units, “Mead Versus Freeman” and “Nature Versus Nurture.”

This episode is included in Season 6 of the SAPIENS podcast, which was made possible by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Trashing an American Icon

[introductory music]

Voice 1: What makes us human?

Voice 2: Who you are.

Voice 3: History.

Voice 4: Your function in community. That’s where we find our purpose.

Voice 5: We are profoundly connected as human beings.

Voice 6: What makes us human?

Voice 7: Let’s find out.

Voice 8: SAPIENS.

Voice 9: A Podcast for Everything Human.

Paul Shankman: It was like dropping a bombshell. I mean, the story first appeared on the front page of the New York Times, and the headline ran something like “New Samoa Book Challenges Margaret Mead’s Conclusion,” and the media went wild.

Kate Ellis: In 1983, Harvard University Press published a new book, Margaret Mead and Samoa: The Making and Unmaking of an Anthropological Myth. Mead had died only five years earlier. The book was written by an anthropologist little known in the U.S. at the time: Derek Freeman.

He’d been working on the book for decades. He’d even offered to send a chapter to Mead, though it seems she never read it. And Freeman … he had a reputation. As he once put it himself, “I am a scientist! Now a scientist is a difficult man. I’m not easily done. I’m obsessive.” Those who’ve studied Freeman’s work, or knew him personally, offered these reflections on the man:

Alex Golub: He was obsessed by the need to dominate others. And then, at times, profoundly regretful of the brutish behavior that he engaged in.

Peter Hempenstall: He’d studied primate behavior for many years and in many ways replicated alpha primate behavior patterns, quite deliberately in some cases I think, to humiliate.

Paul: One of his colleagues says that Freeman had a special place in hell for Margaret Mead.

Bradd Shore: How can I put this nicely? Derek Freeman had a very colorful reputation of being a little bit off his rocker.

[music]

Kate: This is The Problems With Coming of Age. Today’s episode is “Trashing an American Icon.”

We meet Derek Freeman head on: who he was, where his ideas about anthropology came from, and why he seemed to have it out for Margaret Mead.

[music]

Penelope Schoeffel: Derek had read a paper that I’d written, which was published in something called Canberra Anthropology—it was my first publication—and he didn’t like it. And so he told everyone he was going to fail me.

Kate: Penelope Schoeffel, now retired, was a professor at the Centre for Samoan Studies at the National University of Samoa. And she’s the author of Lagaga: A Short History of Western Samoa. She wrote it with her husband, Samoan historian Malama Meleisea. In 1979, she was completing her Ph.D. in anthropology at the Australian National University, where Freeman worked. She’d encountered him before—there had been talk among her advisers that maybe she ought to be supervised by him, since he had expertise on her area of focus: Samoa.

Penelope: And they all thought, “Oh no, you know, he’s a really, really difficult person and that would probably not be a good idea.”

Kate: So she didn’t do it. Once she’d written and submitted her dissertation, she published an academic paper.

Penelope: And then he rang me up, and he said, “You’re another Margaret Mead. That’s what you are.” And he said, “I will be an examiner of your thesis, and I will fail you because you are completely on the wrong track. This is all wrong.”

Kate: Ultimately the university found her a different examiner.

Penelope: I finally got my doctorate after this two-year drama.

[music]

Kate: Freeman seemed to seek out conflict.

Peter: H didn’t suffer fools gladly. He had a very domineering personality and deliberately seemed to deploy that domineering personality to bring other people down, to win every argument.

Kate: Peter Hempenstall is a historian and the author of Truth’s Fool: Derek Freeman and the War Over Cultural Anthropology. It’s a biography of Freeman. The title comes partly from how Derek Freeman saw himself: the court jester, pointing out what ought to be obvious.

Peter: I mean, he saw himself as the great fool of truth. He was a follower of Karl Popper, the extreme logical philosopher who believed that truth could ultimately always be discovered by eliminating error. And so he always set out to eliminate everybody else’s error.

Kate: Including, later in life, Margaret Mead’s.

[music]

Kate: Derek Freeman was born in New Zealand in 1916.

Peter: He grew up in a family—not exactly dysfunctional but with a very strong, powerful mother and, it seems, a rather weak and feckless father.

Kate: He studied at Victoria University College in Wellington, New Zealand, did some work in psychology, and became interested in anthropology.

Peter: He learned about Margaret Mead and really respected her views, agreed with them entirely.

Kate: In 1940, he followed in her footsteps. He went to Samoa to teach. But while Mead went to American Samoa, Freeman headed to Western Samoa, which at the time was a New Zealand colony. His base was the port town of Apia, but he spent a lot of time in nearby Sa’anapu, a remote coastal mangrove village on the island of Upolu.

Derek Freeman: One morning, quite unexpectedly, all of the chiefs of the village assembled and said that they were going to give me a title, an important title of the village.

Kate: That’s the man himself, Derek Freeman, interviewed in the 1988 documentary Margaret Mead and Samoa.

Derek: This title is logona itaga, which literally means “heard at the tree felling,” and it is the title of the heir apparent of the high chief of the village.

Kate: This title meant that Freeman could attend the council of chiefs of the village.

Derek: And it was then that the information that was being brought unmistakably before me, that I began to realize that many of the things that Margaret Mead had reported in Coming of Age in Samoa certainly did not accord with what I was witnessing in Sa’anapu.

Kate: According to Freeman, his sense that Mead got things wrong … it all started here. But it would take him nearly half a century to write and publish his critique. He still hadn’t done any anthropological fieldwork nor had he formally studied anthropology. This changed during World War II. During his naval service, he spent two months at a hospital in Sydney, Australia. He used the time to continue researching Samoa. He pored over archival accounts of missionary work there. After the war, he received funding to study at the London School of Economics.

Peter: He wrote a thesis on Samoa, which was accepted for the diploma of social anthropology.

Kate: That’s Freeman’s biographer, Peter Hempenstall, again. He went on to the University of Cambridge to get his Ph.D.

Peter: He then went on to study the Iban, the longhouse dwellers on the rivers of the western part of Sarawak.

Kate: Sarawak is on the island of Borneo in present-day Malaysia. At the time, it was a British colony. The region became Freeman’s focus. He spent two years among the Iban.

Peter: He wrote a number of reports on them, which have become a staple source for anybody going into the field. He turned out to be a brilliant ethnographer and a very sensitive observer of local customs.

Kate: In the 1950s, Freeman joined the faculty at the new Australian National University in Canberra, continuing to focus on Southeast Asia. And it was around this time that he began to experience some mental health issues.

Peter: He had what we might term today a couple of psychotic episodes, not violent ones, although there was an act of violence in the first one, in Sarawak, when he destroyed a museum piece.

Kate: In 1961, Freeman had what he later called a “cognitive abreaction.” He became convinced that the curator of the Sarawak Museum was making and displaying counterfeit pornographic tribal carvings to misrepresent the Iban. And that this was part of a Soviet-funded plot to undermine the colonial government. Freeman destroyed one of the statues, hoping that he’d be arrested and could reveal to authorities what the curator was up to. Eventually a crew of Australian diplomats and university administrators managed to get him back to Canberra.

Peter: But the psychiatrist who examined him never diagnosed him as having a mental illness or being “mad,” whatever that means.

Kate: Still, the university wanted to put him on medical leave. He refused. Freeman often referred to his experience in Sarawak as a “conversion.” It led him to view human behavior, and anthropology, differently. He began to study primatology and evolutionary biology. Seeing how his own behavior was shaped beyond his control, Freeman became increasingly convinced that it was biology—our genetic makeup, our hormones, our evolutionary background—that most shaped us as human beings. And that the entire idea of cultural determinism—that we are molded by our surrounding—grew from Mead’s misrepresentations of Samoan adolescents.

Peter: He had never let go of feeling—as he went through this whole period of education, or re-education—that Margaret Mead had got it wrong; that her portrait of Samoa as this beguiling romantic paradise where the stakes were not very high, where adolescents were given enormous freedoms to experiment sexually and romantically with one another, particularly the women, before they decided who they were going to marry and what they were going to do with their life. He felt that this was wrong.

[music]

Kate: After Freeman’s episode at the museum, a new research agreement between the government of Sarawak and his university barred him from doing any further work there. So if he wanted to get back into the field, Samoa was his best bet.

But before he arrived, he’d meet Margaret Mead and confront her about her work. That’s after the break.

[break]

Kate: Welcome back to the Problems With Coming of Age.

After his violent episode in Sarawak in 1961, Derek Freeman was determined to find the key to behavior in biology. In his opinion, anthropologists had lost their sense of the discipline as a science. And increasingly, he saw Margaret Mead as a big part of the reason why.

Derek: Margaret Mead visited the Australian National University in 1964, and in November of that year, we had a long private meeting in my study.

Kate: This is Derek Freeman again, from the documentary. Though Mead had likely encountered Freeman at conferences, this meeting in 1964 was apparently the first and only time they spoke at any length. As Freeman tells it—

Derek: I laid before her all of the evidence that I had that indicated that her conclusion was not empirically justified. She was very much taken aback by this and subsequently reported that she felt that her results were now under threat. But when I wrote to her saying that although our conclusions differed, I hoped that there would be no bad feeling between us, and that I would strive to see that there was not. She wrote back to me from New York in December 1964, saying “Anyway, what matters is the work.” And I thought that was an exemplary reply.

Kate: But in a later interview, Freeman admitted there was more to this visit in 1964. During their initial discussion at his office, he gave her a copy of his thesis on Samoa, but she left it there—accidentally or not, we don’t know—and didn’t read it. The next day, at a seminar, they began arguing in front of the graduate students and faculty. Mead asked Freeman why he hadn’t brought her the copy of his thesis to where she was staying, and he replied, seemingly referencing her multiple marriages and affairs, “Because I was afraid you might ask me to stay the night.”

Freeman said, “I was mortified after I said it.”

Paul: Freeman just became more and more convinced that Mead was a terrible person.

Kate: Paul Shankman is the author of the book The Trashing of Margaret Mead, which covers the Mead–Freeman controversy.

Paul: He felt that Mead disliked men, that she had special powers over men, that she was an immoral woman who had had affairs with Samoan men while she was doing fieldwork, which is untrue. She was a liberal. She was a feminist. And she was a person who had publicly embarrassed Freeman.

Kate: This was personal for Freeman, Shankman says.

Paul: Freeman also strongly identified with Samoans. And he wanted to critique Mead, his argument being developed on their behalf. So Freeman really felt like he was a spokesperson for Samoan people.

[music]

Kate: In 1965, a year after meeting with Mead, Freeman returned to Samoa, and that’s when he began to collect the field notes that would bolster his critique. Historian Peter Hempenstall:

Peter: What he disagreed vehemently with was her sense that Samoa was this romantic paradise where everybody got on well, and that if we just let young people [be] free to experiment, that the culture would come out OK. And that young people would come out OK. And that society would travel on.

Kate: Freeman did fieldwork in Samoa over the next two years. And he says he found evidence that …

Peter: Samoa was a very hierarchically and strictly regulated society, particularly sexually, where there was a certain amount of incipient violence, particularly grounded in the way in which children were brought up. And that, in fact, young women in Samoa were highly regulated sexually. There was almost a cult of virginity, he claimed, among Samoan women.

Kate: Anthropologist Penelope Schoeffel says that Freeman used this understanding of Samoan sexual norms and values to draw conclusions about their everyday behavior.

Penelope: He saw the Samoans as being very rigid people, which I think anyone who knows Samoan people knows that Samoans are not very rigid.

Kate: His depiction of the church congregation—the communion—was one example.

Penelope: He had this very strong belief that if you were in the communion, you couldn’t possibly be a nonvirgin because you would have had to withdraw. Well, I mean, that’s nonsense. No girl who’s lost her virginity is going to leave because otherwise everyone in the village is going to know, “Uh oh. What have you been doing?” You know?

Kate: Freeman drew mostly on his interactions with chiefs. Mead, on the other hand, generally relied on her conversations with young women and girls. Freeman also felt he had to somehow defend Samoans from Mead’s representation of them as promiscuous or sexually permissive. But Schoeffel questions his methods. She remembers him interviewing her husband Malama Meleisea and even secretly videotaping him to make observations about Samoan behavior.

Penelope: At one stage, Derek wrote to Malama—I kid you not, he’s still got the letter—saying, “How many virgins are there in your village?” And Malama didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. He thought, “What? You think I’ve been through all of them?” [Laughs]

Kate: Earlier we said that Freeman was motivated by eradicating error in the world. He also felt that Mead’s work had set a course for anthropology that needed correcting. In his view, she’d focused too much on culture at the expense of biology.

Penelope: He believed that social theory was all rubbish

Paul: He felt that she was an absolute cultural determinist and allowed no role for biology. Freeman felt that she was anti-scientific, anti-evolutionary. In other words, Mead was wrong, wrong, wrong.

Kate: This conflict often gets framed as nature versus nurture. Freeman thought that Mead went looking for evidence that would support her belief that behavior was driven by culture alone, that it was all nurture. Peter Hempenstall:

Peter: One of the great criticisms of Mead that he made, about her book, was that it was a project designed to please her supervisor, the great anthropologist Franz Boas, to prove that, in fact, cultural conditioning was the key, the great impulse, to human evolution.

Kate: And Freeman found this to be unscientific. To him, anthropologists, especially the cultural anthropologists in the U.S., had focused so much on culture that they had lost sight of the importance of biology.

Peter: He wanted anthropology to become something other than simply the ethnographic study of cultures because he believed that to understand cultures, to understand humans within culture, you had to understand their genetical background.

[music]

Kate: But this focus on biology and genetics? It can lead to some pretty questionable science—essentially the same kind of pseudoscientific racism that Boas and his circle had been combating in the 1920s. Views that helped propel eugenics and the notion of racial improvement and planned breeding that culminated in the lethal tenets of the Nazi regime and continue to reverberate today. Freeman himself might not have held those views, but it’s part of why his work drew so much attention. And he did seem to relish taking on contrarian positions.

Derek: Well, I have always been a heretic. I think being a heretic is the most beautiful thing because this comes from a Greek root, meaning someone who chooses for himself. In other words, a heretic is someone who thinks for himself and doesn’t run with the mob. And I have always been a heretic and found great joy in it.

[music]

Kate: In 1978, in one version of the story, Freeman offered to send an “acutely critical” chapter to Mead. She never responded. That year, she died. Five years later, Freeman’s book came out.

Peter: It takes him 20 years to write the book on Margaret Mead and Samoa, and then all hell breaks loose, of course, when he does write it.

Kate: Freeman’s publisher, Harvard University Press, sent him on a publicity tour across the U.S., and he got a lot of criticism from academics and anthropologists.

Peter: And Derek Freeman, being the kind of domineering personality that he was, could not simply sit back and take the criticisms that were being thrown at him.

Kate: The debate between Mead’s legacy and Freeman’s critique played out in the public eye. That New York Times headline “New Samoa Book Challenges Margaret Mead’s Conclusions” was just the start.

[music]

Paul: Freeman got a lot of attention. And, unfortunately, the headline in the New York Times stuck. People thought maybe Mead was wrong. They may not remember Freeman by name. They may not remember the details of his critique. But Freeman had planted the seeds of doubt about Mead’s credibility. And that was enough to tarnish her reputation. I mean, she had gone from public icon to cultural roadkill in just a matter of months.

Kate: For Samoans and anthropologists, however, this went beyond nature versus nurture. It was about whether Freeman or Mead had managed to portray Samoan culture accurately.

Penelope: Ethically, I don’t believe she thought she was doing a bad thing to Samoan people. I think she really did believe that it was socially accepted. How would she not know? Who were her informants, you know? And I think that this was one of her fatal mistakes: confusing private behavior with public morals and expectations. Whereas with poor ol’ Derek, he took it to the opposite extreme, you know, that no Samoan would ever do that, and all Samoans live in fear of being struck dead by God and all that sort of stuff.

Kate: If she had to pick one anthropologist over the other, Schoeffel says she thinks Freeman got things more right.

Penelope: He had a far better picture of Samoa in that book than Margaret Mead did. It was a very dark portrayal of Samoan society, but it was far more a Samoa I recognized than Coming of Age.

Kate: Still, both Mead and Freeman portrayed Samoa as frozen in time. They took their set of observations and used them to draw broad conclusions about a kind of unchanging Samoan society.

Penelope: You can’t say Samoa is like this or like that. The idea that you could, represent a culture by just looking at one or two families or interviewing 20 teenage girls. I mean, that’s probably one of the great weaknesses of anthropology.

Kate: To Schoeffel, there’s one aspect of Samoan culture glaringly absent from Mead’s portrayal. Mead writes about the church, but it’s not central to her account.

Penelope: Now why was that? Why didn’t she mention the fact that these girls would have all been practicing Christians, going to church every Sunday, probably twice on Sundays, wearing their white dresses and their white hats?

It’s because Margaret Mead doesn’t want Americans to know about the “primitive” people going to church every Sunday and having a minister and all that; she wants to present them as being “the Other,” you know, different.

[music]

Kate: Both Mead and Freeman sought out Samoa as a place removed from the West. But in truth, Christianity and colonization had been shaping the islands since the arrival of the first missionaries in the 1830s.

So before we see how the clash between Mead and Freeman played out dramatically and publicly, we need to step back in time, to where the modern ideas of sexuality and adolescence in Samoa began—the church and its outsized role in Samoa. That’s next time.

[theme music]

Kate: The Problems With Coming of Age is a co-production of SAPIENS and PRX Productions.

Be sure to check out the season’s college curriculum, historic photographs, and so much more on our website: SAPIENS.org/podcast.

Doris Tulifau: This episode was written and produced by Rithu Jagannath, Ashraya Gupta, and Ari Daniel. This season was hosted by Kate Ellis and me, Doris Tulifau.

Kate: From SAPIENS, we were supported by Chip Colwell, Tanya Volentras, Esteban Gómez, Sia Figiel, Salamasina Figiel, Sophie Muro, and Christine Weeber. The season’s humanities advisers were Danilyn Rutherford, Lisa Uperesa, Nancy Kates, David M. Lipset, Nancy Lutkehaus, Agustín Fuentes, Don Kulick, and Paul Shankman.

Doris: And fa’afetai to the more than three dozen people we interviewed in American Samoa and Samoa for helping to shape our understanding of this story.

Kate: The executive producer of PRX Productions is Jocelyn Gonzales. The project manager of PRX Productions is Edwin Ochoa; the business manager is Morgan Church.

Doris: Dan Taulapapa McMullin created the season’s cover art. Celina T. Zhao was the fact checker.

Kate: Audio mastering by Terence Bernardo.

Doris: Music by APM with additional tracks by Malō Fa’amausili recorded at Apaula Studio as well as songs kindly provided by Bobby Alu.

Kate: SAPIENS is part of the American Anthropological Association Podcast Library.

Doris: And SAPIENS is an editorially independent podcast funded by the Wenner-Gren Foundation, which has provided vital support. Our thanks to the foundation’s entire staff, board, and advisory council. Season 6 of the SAPIENS podcast was made possible by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Doris: I’m Doris Tulifau.

Kate: And I’m Kate Ellis.