The Gift of a Bicultural Upbringing

I remember distinctly the moment I realized I had two childhoods. I was in third grade and had waddled down the hill of my suburban German neighborhood to wait for the bus. My best friend was waiting there with her mother, and an exasperated group of parents was discussing the head lice epidemic plaguing our school. When I arrived, my friend’s mother turned around to scrutinize me.

“Let me see your head!” she demanded. “You have spent so much time in India, and people over there are very unhygienic, so you probably brought in the lice!” Then she added: “It’s just very different over there. They don’t have the same standards. Your parents really shouldn’t take you to such a place!”

As she examined my scalp, I gulped in a failed attempt to swallow rising tears. I didn’t know why, but I felt sad, slightly ashamed, and out of place. Later that day when I relayed the story to my father, he was furious. While he raged about prejudice and racism—big words I didn’t fully understand—I thought about my double life.

Every year between the ages of 5 and 13, I went with my parents—both trained anthropologists and scholars of South Asia—to the Himalayas, where my mother conducted in-depth fieldwork. I learned Hindi, and the family we stayed with became our family.

Half the year I went to school in Germany, took flute lessons, and competed on the swim team. The other half, I learned about Himalayan agriculture, watched water buffalo and goats wander through our village, and excitedly awaited the newest Bollywood films. I loved both places. Both were home. And even though the settings couldn’t have been more different, I never truly drew a line between Germany and India in my mind.

But after the lice incident, I wondered: Was there something wrong with my village life? Was it weird? Were my friends there so different from my friends here? It began to dawn on me that my life had two different parts. And I thought, if I want to truly belong to one, would I have to give up the other?

Over the years, as I’ve seen the world increasingly divided by notions of “us versus them” and have set out on my anthropological studies of caste issues in India, I have reflected on these issues frequently.

Most people are taught from a young age to make distinctions between themselves and “others” or “here and there.” But the children of anthropologists—much like other children raised in a cross-cultural environment—frequently struggle to make those distinctions. Their upbringing profoundly shapes the ways they interact with people from various cultures and places who hold vastly different viewpoints.

So, I believe the lessons from an anthropological childhood are particularly important today as “us versus them” debates dominate sociopolitical conversations. These lessons can help people answer powerful questions about belonging, “othering,” and connecting: Does truly belonging in one group mean we must “other” people who are outside that sphere? Is universal empathy only possible by living as an outsider? And most important of all, how can we connect with people whose lives and perspectives seem so different from ours?

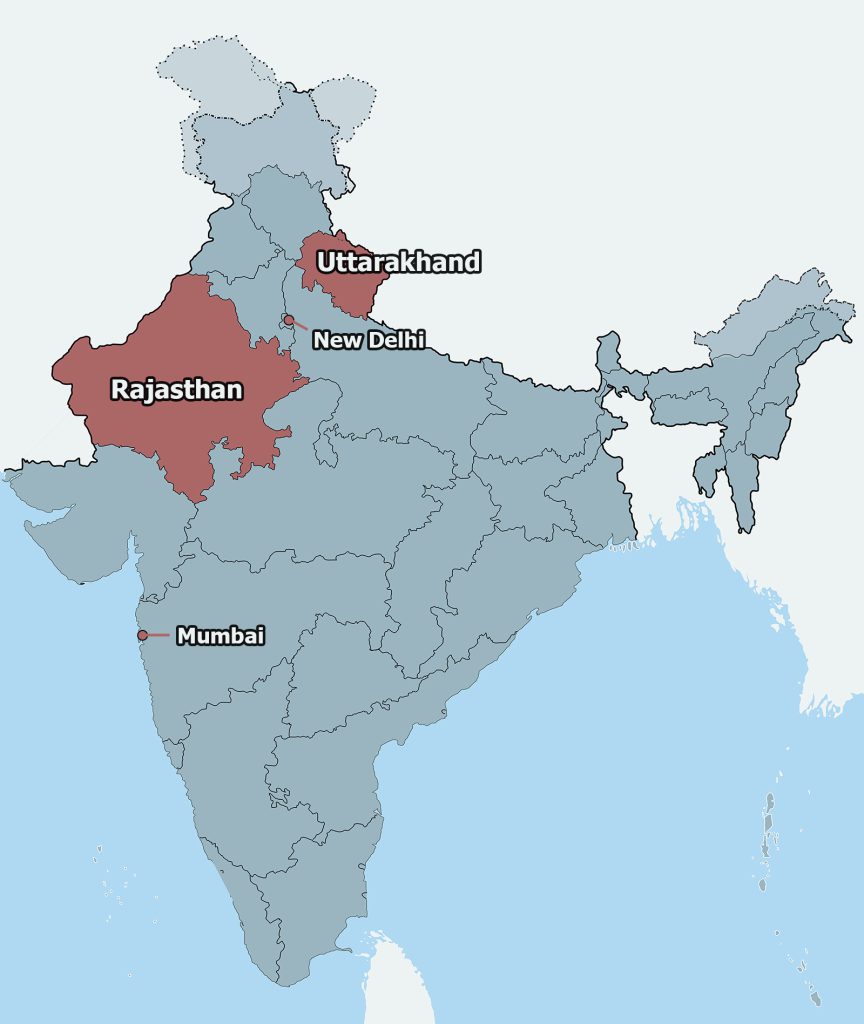

In the 1990s, when my mother conducted fieldwork, she was never without her camera. She owned a slightly battered vintage Kodak Six that she loved fiercely. Watching her from the backseat of a car, or from the squeaky wooden balcony of the room we rented in a joint family home in what is now the Indian state of Uttarakhand, I used to think research consisted mainly of photographing the world and people around us.

The route to a new sense of familiarity and belonging tends to follow the same bends in the road.

The images of my mother climbing on rooftops, wading through dense crowds, or stopping the car without warning to get that one good shot have haunted me. They haunt me because unlike her, I was never so keen or comfortable taking that shot—a photograph that essentially marks its creator as an outsider. And I always felt a little uneasy admitting I was an outsider.

Even though I understood on some level that we were moving between countries, I did not conceive of Germany and India as separate experiences. They were just different seasons with different friends, and I always enjoyed telling one about the other. Happily unconcerned with disparities between nations or communities, I simply looked forward to the different moments of my life spent entertaining people (and sometimes goats) anywhere.

“I think we intuitively learn to fit in,” says a friend whose anthropologist mother also dragged her around the world. “I don’t mean in a follow-the-peer-pressure kind of way. I mean in the sense that you kind of always know what it means to make community and be part of it. And you realize that the process is the same wherever you go.”

Her statement points to an important insight: As much as we learn something novel when moving to a new cultural setting—how to prepare a meal, greet someone, or tell an appropriate joke—the route to a new sense of familiarity and belonging tends to follow the same bends in the road.

As different as cultures are on some levels, the process of open engagement and interaction that forms the heart of home and belonging is probably similar everywhere. In this process, different ideas of family life or what registers as funny bleed into one another. Without needing to be compared, demarcated, or analyzed, these habits simply coexist—sometimes separately, sometimes in conversation with one another.

At the same time, intuitively learning to fit in everywhere comes at a cost.

When my mother did fieldwork, her tendency to jump around with her enormous camera or travel without a male companion—even though other women in the village would not—was accepted. If her behavior inspired some gossip, she was still entitled to her eccentricities as a “Western woman.”

But for me, expectations seemed different, both when I was growing up in Uttarakhand and when I later conducted fieldwork in Rajasthan, India. The transgressions my mother was allowed were, while possible, certainly more discouraged for me—someone who spoke Hindi fluently and had adopted particular cultural mannerisms and local forms of humor from a young age.

“Sandhya may look Western, but she is one of our girls,” the mother of my host family in Rajasthan used to tell people. “She doesn’t behave like most Westerners.”

Even when I spent a week volunteering in a refugee camp in Swaziland (now called Eswatini), a country I didn’t get to know until much later in life, the camp manager, a Swazi mother of four, used to squeeze me tight and say, “You are a good girl—just like one of ours.”

Implicit in both statements was a responsibility to adhere to local codes and behavioral boundaries that outsiders—including my mother—were exempt from. Perhaps it was self-imposed, but there seemed to be a subtle contract of belonging that I had to negotiate in a different way and that demanded a level of conformity. This is the price of blending in.

Because of this, children who grow up immersed in anthropologic field experiences can simultaneously be the ultimate insider and the forever outsider. Equipped with the behavioral, psychological, and linguistic toolbox to become part of many worlds without drawing categorical boundaries between them, we exist more directly at the margins than most. Adopting a single national, professional, or personal category of identity seems suffocating.

But does that mean people can only truly belong to a group if they conform? Can those who live at the margins between groups and places still have a sense of belonging?

My partner, who was born and raised in Southern England, was heartbroken when his parents sold his childhood home when he was in his late 20s. He says it made him feel like he had lost not only a home, but an identity. His sense of belonging was spatial. Home was a place, a family, and a community at a particular point in time. He was determined to buy the house back someday in order to rebuild his fractured sense of belonging.

I empathize with him, but I can’t fully comprehend his need for geographical settledness. Home for me has always been my family. Home is wherever they are.

On the other hand, unlike my partner, I have often agonized about the no man’s land of my identity. I never feel more German than when I live far away from Europe. At the same time, I am most certainly not Indian or anything else. In India, I am a Westerner. To the Americans with whom I attended college in Maine, I was European. My British boyfriend thinks I am quite Continental. And in Germany, I still am that strange kid who grew up in India.

Despite all this, I believe people who lack a certain rootedness can still have a sense of belonging.

People tend to think of belonging as a binary option: You either do or you don’t. In reality, most people negotiate shades of belonging in different areas of their life. Someone might acknowledge deep roots in a place they no longer live in and don’t plan to return to. Someone might be raised in a certain religion yet become nonreligious.

People who are unfamiliar can nonetheless be yours.

These scenarios don’t imply that a person does not belong. Rather, their feelings of belonging are simply different: They can be multiple, dual or singular, liminal or complete.

Growing up inside a community, yet traversing between places and ways of belonging, can teach you countless valuable lessons: People who are unfamiliar can nonetheless be yours. The opposition between you and the “other” ultimately doesn’t hold up. You have a capacity within you for growth and otherness—to become multifaceted. You can be part of many things without losing yourself. Not being completely one thing does not make you a person without a home or an identity but someone who can belong in myriad places with a variety of people.

This perspective has profound implications for today’s increasingly divided world.

During my fieldwork in Rajasthan, I worked with Dalits, members of India’s lowest caste who are also referred to as “untouchables.” I was surprised that many of my Dalit informants, who had explicit concerns about the discrimination and exclusion they experienced daily, seemed unwilling to extend their concern to other communities.

When I told a Dalit activist that I was visiting a Muslim family in the neighborhood, she was appalled. “You should stay away from Muslims,” she warned. “They treat women really badly and strategically try to have as many children as possible to become a stronger political force!”

I was stunned. As a woman who devoted her life to battling the caste-based prejudice and abuse that she deemed inhumane, how could she speak about other groups in this way?

Abstract notions of “us versus them” are at the heart of Brexit, U.S. immigration policies, and the growing influence of nationalist parties in Germany, India, and elsewhere. Discussions about distinctions cause us to wonder whether it is possible to be part of different communities on equal terms or whether truly belonging to one group means exclusion from all others.

What I’ve learned from an anthropological childhood is this: Having a deep feeling of being part of a community, nation, or place doesn’t limit a person’s capacity for empathy. But embracing a multifaceted notion of our identity prevents us from drawing potentially dangerous lines between us and other cultures, professions, countries, or political parties.

What makes a person genuinely able to embrace difference is a moment of stepping across the boundaries of one’s early identity and the assumptions that accompany it. This allows for the emergence of new questions, new ideas of selfhood, and new social connections. We must be willing to face the possibility of finding ourselves out there at the margins between groups, and to welcome the discomfort of growing and learning in ways we never expected.

This growth may ultimately lead us away from the security of a comfortable, unquestioned sense of belonging. And it will make it almost impossible to declare an entire country an unhygienic place filled with strange people, the way my friend’s mother described India. Because a view like that from inside a contained culture, surrounded by emotional glass walls, distorts the way we can and should think of others. That protective glass denies us the potential for connection.

Two years ago, I met up with my primary school friend, the one whose mother catapulted me into a precocious identity crisis.

“I am doing a master’s in anthropology now,” she told me, to my utter surprise. When I asked her about her decision, she replied: “I don’t know, there was just something about hanging out with you and your parents that made me realize that faraway places or people in other cultural contexts don’t have to seem far away. It made me feel like I didn’t even understand what ‘difference’ meant and that maybe I had all these wrong ideas of other places. I looked at your family and thought, ‘They are all anthropologists; maybe if I study anthropology, I will see the world in a new way!’”

I hope she will. An anthropological life—whether it be one given to you in childhood, one you explore in a university while doing fieldwork, or simply one you adopt as an outlook—is one whose heart beats to the notion of interaction. Personal interaction has the power to counteract the dangers of abstraction. And it allows us to embrace a multiplicity of belonging in such a way that we never have to feel rootless or marginal.