Dating Apps Can Gauge Attraction but Not Chemistry

On a warm spring night in Beirut, Lebanon, I sat in the garden outside my apartment chatting with Michael and Mano. [1] [1] All names have been changed to protect people’s privacy. I had gotten to know the two best friends well during my time researching online dating in the city. Michael—a Lebanese American man who, at 27 years old, was looking for love—told us about a recent date with a guy he’d met through the gay hookup app Grindr.

Michael had first been attracted to the guy’s photos. The text conversation leading up to the date was “all nonstop jokes and sarcasm,” Michael said. “All was going right. He gets me, I get him.”

“Then we met,” Michael told us. “It was the most boring date I’ve ever had.”

Mano and I groaned in understanding.

Despite their fun banter and Michael’s initial attraction, the pair had no spark in person. Had one of them lied or misrepresented themselves in the chat? No. The truth was more banal: A connection online simply didn’t guarantee a connection offline.

For anyone who’s used dating and sex apps to meet people, Michael’s tale has a familiar arc: We build desire through conversation only to have these feelings shift once in person, for better or worse. But why?

As an anthropologist who studies the effects of technology on how we experience connection in the digital age, I’ve come to think of this experience in terms of a deepening division between “attraction” and “chemistry.” The overlap between these emotions is shifting as our intimate lives become increasingly tied to digital media. Thinking through this division sheds light on the disconnect many of us feel as our connections move from the online space of profiles and mediated conversations to the offline realm where bodies meet.

HOW DATING APPS MEDIATE ATTRACTION

According to biological anthropologist Helen Fisher, we all carry a “love map” in our brains. This refers to the conscious and unconscious list of partner criteria that people have internalized. When we see someone who comes close to meeting these criteria, it activates parts of our brains associated with love and attraction. Knowing if someone has the qualities that fall within our love map requires observing people in context—speaking with them and observing their nonverbal gestures, facial expressions, outward appearance, and cadence of voice.

But in the age of online dating, we often come to first know people in a different way: as verbal and textual information contained within the predetermined order of the interface design.

As anthropologist Sofian Merabet explores in Queer Beirut, the advent of digital spaces starting in the 1990s changed the ways queer men in Lebanon communicated about sex and relationships. Connecting over online chatrooms and message boards ushered in a novel sense of agency and possibility among queer men over their sex lives, which Merabet describes as new kinds of “erotic imaginations.”

But the openness of these connections shifted over time. Eventually, queer men began formalizing these exchanges into a shared language about who and what they desired in a partner. The exchanges about sex and intimacy became more predictable.

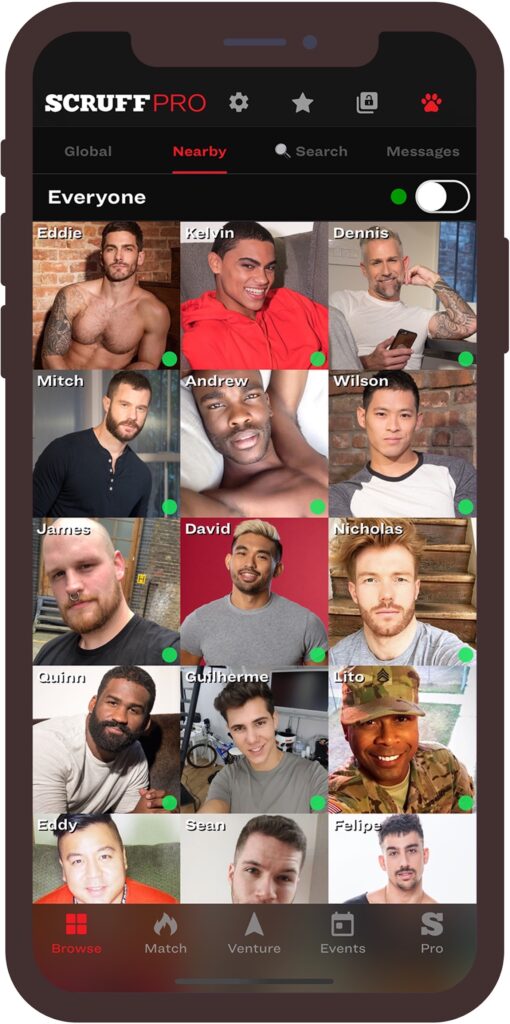

These days, as I found while living in Beirut, mobile apps like Grindr and Scruff have become the primary ways that queer men connect. The apps are so popular that men told me if they stopped using these apps, they would see it as a decision to give up on sex and intimacy entirely.

COMPUTING DESIRE

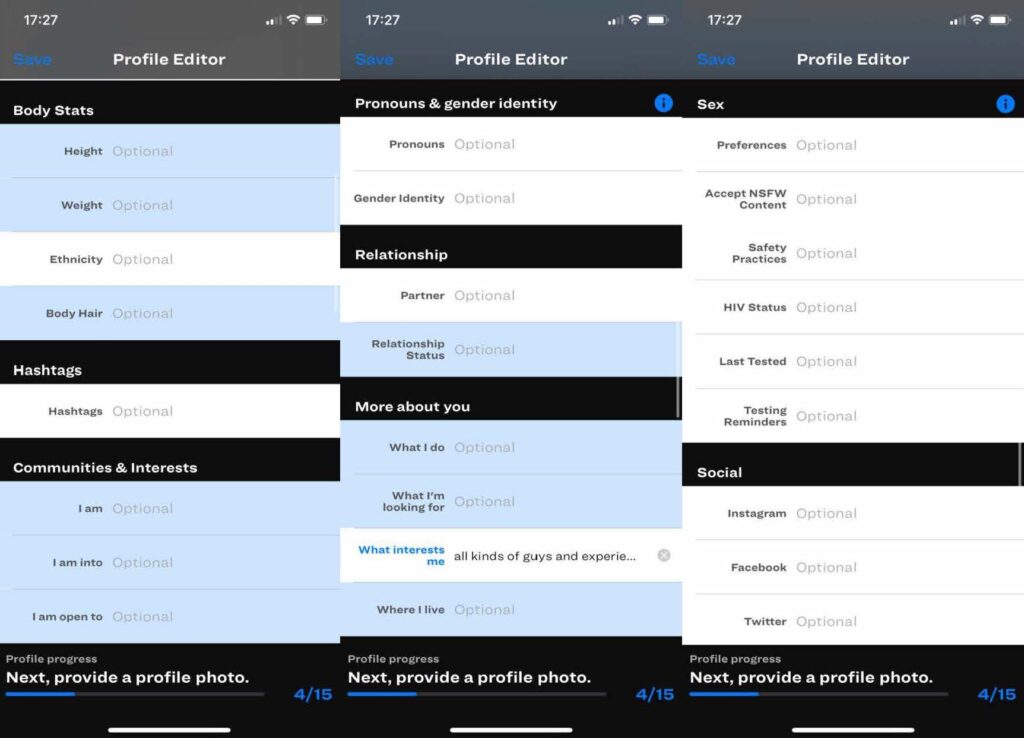

Attraction and information seem to pair well in the digital age. Dating and sex apps put the contents of our “love maps” front and center as discrete pieces of information neatly organized within the digital interface.

I often asked queer men in Beirut what attracted them to other people online. They typically answered by listing pieces of discrete information they could find on the apps, as opposed to less measurable qualities like generosity or kindness.

The way these apps gather data and predict matches can sometimes deepen biases, as theorist Kane Race argues. They make it easy to search for potential partners based on criteria such as height, body type, age, ethnicity, and personality traits—and to filter out those who don’t fit a person’s idea of what attracts them. Researchers have repeatedly shown that people who don’t fit preferred body types, ages, or racial or ethnic identities face discrimination on dating apps.

My friend Nadeem, a digital app designer, used these technologies only for sex. He explained to me how the Grindr and Scruff interfaces ask users to show photos of their bodies, candidly share their desires, and list their proximity and availability. Nadeem, like many others who saw the apps as facilitating short-term connections, always felt justified in talking explicitly about the possibility of sex with matches; that was, in his view, what the app was designed to do.

When Nadeem perused the apps, he looked for profiles that met his specific set of criteria. He wanted swarthy, hairy men with relatively large physical endowments who preferred the bottom role in sex and had private space to host him. If initially attracted to their photos, he’d start chatting with them, where he’d continue to collect information about their preferred sexual roles, desires, and availability.

Depending on their answers, his attraction might wax or wane. Nadeem said this process rarely failed to produce good sex and pleasant encounters. When it did fail, he attributed it to having missed a key piece of information. It always seemed to me as if he was trying to compute away the messiness of sex and desire via orderly, standardized variables.

ATTRACTION VS. CHEMISTRY

The information on apps promises to make possible lovers knowable. Still, many app users saw the profiles as just a starting point for getting to know someone.

Awad, a young man of Lebanese and Latino background I got to know as a neighbor, told me: “When I see the age range I like, a good weight-height body ratio, a fit or average body type—I reply when I see someone like this. Or, when they write something nice or interesting.” For Awad, there wasn’t one single piece of information that mattered but rather the pattern as a whole and what it said about a person.

Read more on the digital era from the archives: “The Age of Digital Divination.”

Michael, even more so than Awad, required more than attractive pictures and arousing details to decide to meet a man offline. He looked to the cadence of the online conversation and the quality of the banter to try and guess whether he would feel something more than attraction. He called it chemistry—that ineffable feeling that can only really be felt in person.

If attraction comes from ordering information into pleasing mental images and expectations, then chemistry is the unpredictable antidote to that order. Men often told me that chemistry, or the lack thereof, could implode all the expectations someone might have going into an encounter. That’s why my friends often met up quickly with matches on street corners all over town to test whether their feelings of attraction would turn into chemistry in person.

The anthropologist Nick Seaver found a similar dynamic at work in his research on music recommendation algorithms used by companies such as Spotify. He points out the tech industry understands itself as a source of order in a world beset by information overload. This includes dating and sex apps that promise to help people find matches through predictable, information-based attraction. Yet, chemistry often defies these logics: People can have amazing chemistry even if they don’t come close to satisfying one another’s criteria.

Seaver points to a similar tension within the world of music recommendations, which rely on formal rationalization and patterning of informational systems to try and predict users’ listening habits and preferences. While these algorithms often get it right, they don’t always match up with a user’s “taste.” Taste, like chemistry, can be more socially and culturally open than a person’s listening data might suggest.

Data-driven attraction might compel someone’s initial decision to meet in person, but what happens after depends on chemistry. Ultimately, the difference between attraction and chemistry speaks to the limits of technologically mediated information to render our intimate lives measurable and controllable.

Queer men in Beirut taught me that in a world where everyone is trying to connect, attraction is more abundant than chemistry. But chemistry was what most men were after. They wanted to maintain the possibility for intimacy to unfold in fluid, unexpected ways—following patterns of desire that no app can predict.