90 Years Since Its Discovery, a Stone Age Human Still Holds Lessons

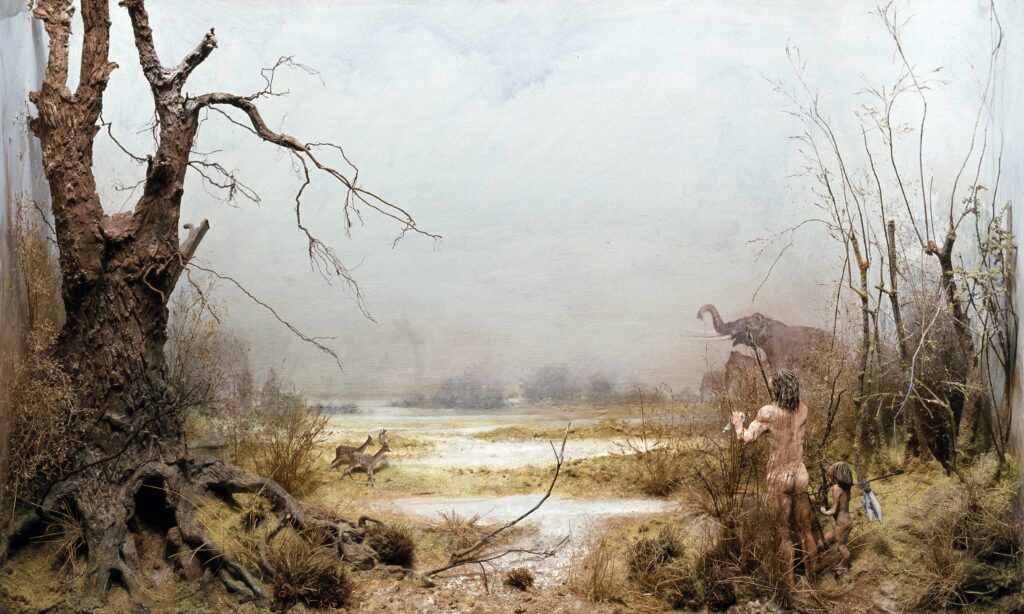

Southeast England. 400,000 years ago. A young woman squats by a river that will eventually be called the Thames. Her wide feet press into the cool, pebbly bank. Swampy wetlands and lush forests sweep behind her.

Then: It’s over.

A lion feeds her cubs. What’s left of the woman is quickly covered by the river’s silty clays.

This Pleistocene woman—known as the Swanscombe fossil—now rests at the Natural History Museum, London, where I work as a paleoanthropologist. We researchers don’t really know how she died, but I have imagined the scene. Lions did roam her world.

This year marks the 90th anniversary since the Swanscombe remains were recovered. To commemorate this “Granite Jubilee,” I looked back on how scientists’ views about the fossil have shifted over the years—from initial interpretation of the fossil as an early Homo sapiens and symbol of “British Exceptionalism” to its current status as a Neanderthal ancestor, representing a minor part of a global human story.

Its changing interpretation across the 20th century exemplifies how the field of human evolution itself has evolved. Immersed in dusty archives of personal letters, newspaper clips, and journal articles, I found a history I was not expecting: the influence of personality, politics, and power on scientific interpretation.

The Swanscombe fossil’s story began before it was uncovered in 1935. By then western Europe had a long history of archaeological exploration. For decades before, amateur and professional archaeologists roamed the continent, seeking fossils of long-gone creatures, including human ancestors. A small comparative sample of fossils were available from outside Europe, often recovered from places under colonial rule or previously under such rule, such as Zambia and South Africa.

During the first half of the 20th century, researchers of human origins produced knowledge through detailed anatomical descriptions accompanied by “authoritative pronouncements” on their meaning. Nowhere to be seen were the phrases of uncertainty—“may suggest,” “possibly indicates,” and so on—that pepper and temper conclusions in contemporary science. And the ideas of British scholars enjoyed particular influence and esteem globally.

At the time, many European scholars studying paleoanthropology thought humankind arose in western Europe. Some British scholars went further: They favored the idea that Britain was the cradle of humanity—or more accurately, the cradle of White, European H. sapiens. From my 21st-century vantage point, I saw how nationalist and patriotic ideology clouded the conclusions of earlier British scholars—and set back thinking for decades.

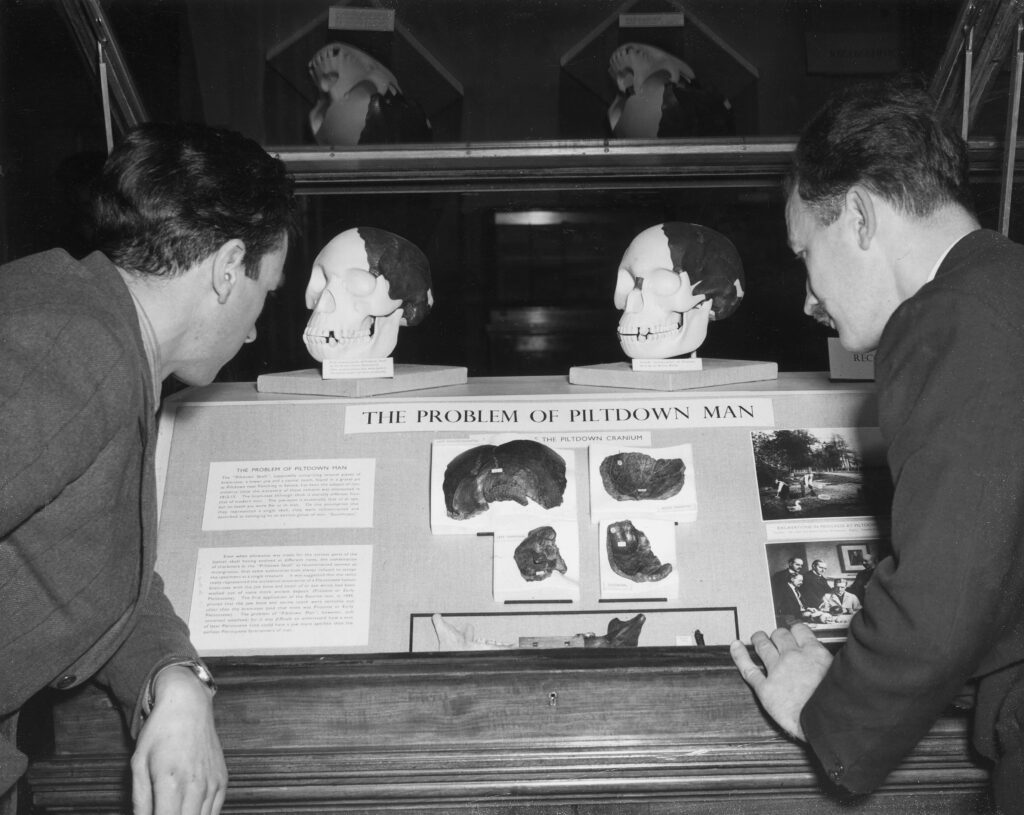

And of course, I know something those earlier scientists did not: Piltdown Man, the fossil that served as the bedrock of the human-origins-in-Britain hypothesis, was a hoax.

“Discovered” in southeast England by its likely creator Charles Dawson in 1912, the Piltdown “fossil” was a H. sapiens skull, an orangutan jaw, and a chimpanzee tooth, colored, concocted, contrived, and carved. The resulting amalgam gave a caricature-like appearance of an ancient “missing link” between ape and human living in the region 500,000 years ago.

The Piltdown Hoax gave British scholars the evidence needed to prove the deep antiquity of “The First Englishman.” It held until 1953, when the creation was definitively proven to be a hoax.

Within this research milieu, in summer of 1935, Alvan T. Marston stood in an abandoned quarry near Swanscombe, England, about 23 miles east of London. The baggy-trousered amateur archaeologist was a regular in the pit.

On a day in June, he spotted what appeared to be part of a human skull poking out of the quarry bank. Being without a camera, he decided to remove the fossil and mark the site of discovery. He took the fragment to a local pharmacy to wrap it in cotton-wool then wrote immediately to the Geological Survey in London.

This bit of cranium was the first of three pieces that would come to constitute the Swanscombe fossil—the first authentic remains from an extinct human species discovered in Britain. Although incomplete, the 400,000-year-old cranium shows incipient resemblances to later Neanderthals and therefore is considered an early member of our extinct cousins—at least by today’s scientists.

But 90 years ago, scholars waved away its Neanderthal-like features because they held onto their presumptions that our species, H. sapiens, arose in western Europe. The fossil was used to bolster support for the fabricated Piltdown Man as an authentic H. sapiens—and suppress emerging ideas that the origins of humanity lie outside Europe.

English scientific institutions have not changed much since Swanscombe was unearthed. Halls and studies I work in today resemble those of the early 20th century. As I investigated the fossil’s history, it was easy to imagine the settings of its research.

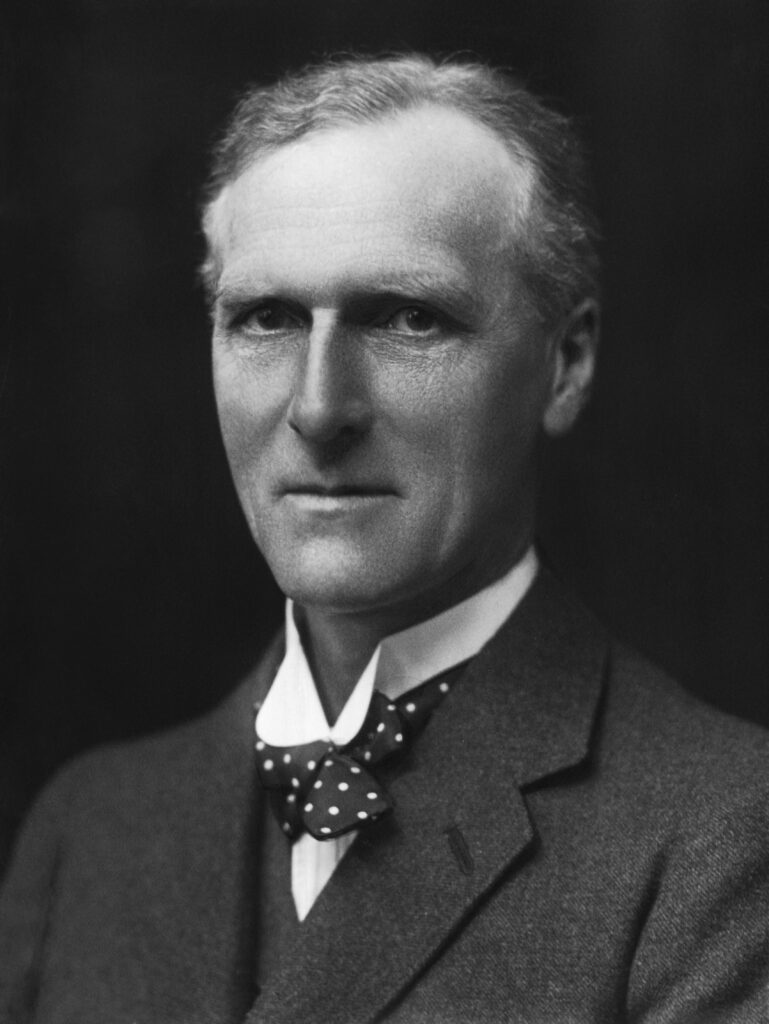

Narrow Georgian windows cast light across austere wooden furniture. Floor-to-ceiling shelves exhale the scent of rare books. It’s 1938 at Down House, Charles Darwin’s former home. Sir Arthur Keith—a renowned anatomist and leading authority on human origins—is preparing to expound on the Swanscombe fossil.

In 1938 and 1939, the Journal of Anatomy published dozens of Keith’s hand-drawn sketches of Swanscombe, which identified more than 100 points of measurement around the cranium to compare with Piltdown.

Despite the richness of these data, Keith shoehorned his findings into his existing narrative. In Swanscombe, Keith saw what he wanted to see: He declared Swanscombe the second-oldest representative of H. sapiens, right after Piltdown. Today paleoanthropologists know Piltdown was a forgery and Swanscombe likely belongs to the lineage leading to Neanderthals—not H. sapiens.

Keith also leveraged this work on Piltdown and Swanscombe to suppress the research of scientists who looked beyond Europe for humanity’s origins. Among them, Raymond Dart stood out to me, in part because we are both Australians trained as paleoanthropologists in London. But also because his dismissal by figures such as Keith delayed the acceptance of Africa as central to human evolution for 30 years.

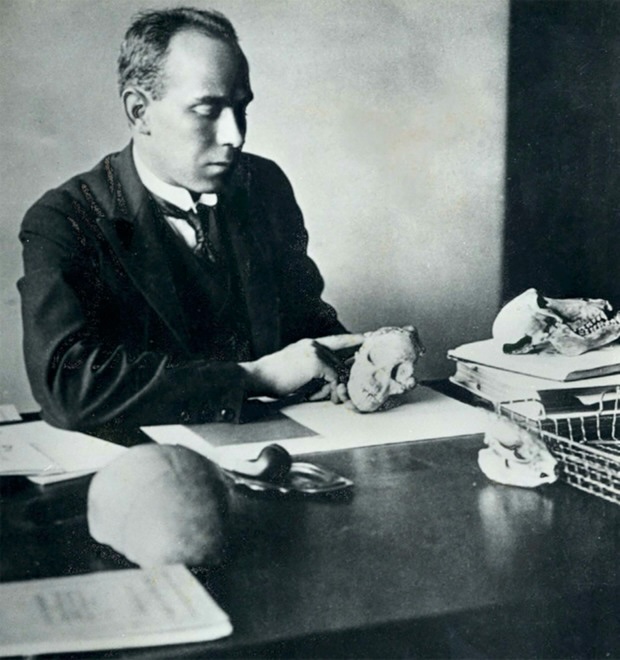

Dart was trained and mentored in London by the British anthropological establishment before moving to South Africa in 1922 to work at the University of Witwatersrand. In 1924, he was given a small ape-like skull that local quarry workers had plucked from their rubble.

His careful analysis revealed many of the bipedal adaptations and intermediate characteristics between humans and chimpanzees that Charles Darwin had predicted would be found in Africa. Dart rightly concluded that this fossil, which he named the “Taung Child,” suggested Africa—not England, nor western Europe—was the cradle of humanity.

Keith called Dart’s hypothesis preposterous, declaring Dart too inexperienced to know what he was really examining—just a juvenile ape, according to Keith. The Royal Society refused to publish Dart’s detailed 269-page manuscript on the fossil. Dart’s colleague in South Africa, Robert Broom, wrote in 1950, “[the] English culture treats him as if he had been a naughty schoolboy.”

By the time the Swanscombe fossil was recovered, Dart had stepped back from paleoanthropological research due to the emotional wounds suffered from the scathing reception of the Taung Child. Despite being a brilliant neuroanatomist, uniquely suited to study Swanscombe, Dart did not assess the skull. Had he, perhaps the fossil’s likely identity as a Neanderthal ancestor would have been known long ago.

It took an additional two decades of fossil discovery in South Africa before Keith admitted in a 1947 letter to Nature “Dart was right and … I was wrong,” about the centrality of Africa to our human story.

Though Dart was eventually vindicated, I found it unsettling to read how the biases and geopolitics of people like Keith shaped the research landscape. Because Keith didn’t think he was biased. He thought he was doing rigorous science. He had all the training, all the anatomical expertise. From inside his own head, he was the careful, objective one, and Dart was an inexperienced upstart, a traitor to his intellectual English heritage.

As I sat in a similar institution to Keith, working on the same material, I wondered: How do these intellectual roots influence my work as a paleoanthropologist in 2025?

In some ways, the 1930s paleoanthropology I read about felt alien. For example, unlike 90 years ago, at the London Natural History Museum today, we complete training in unconscious bias, have flourishing support groups for underrepresented identity groups, and celebrate diversity of nature and humanity alike.

Yet in some ways, my field that studies fossil ancestors felt fossilized.

In 1935, British institutions wielded the power to elevate or suppress research. Ninety years later, several leading research institutions exist outside the Euro-American sphere, such as the National Museums of Kenya and Tanzania, and the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing. Nevertheless, intellectual and financial power remain concentrated in Euro-American institutions, which continue to lead excavations in countries that were once European colonies. Research collaborations, funding, and access to specimens and technology continue to be negotiated within a colonialist, power-imbalanced context.

And as for authority? Some metrics of scientific success, such as social media following, didn’t exist even 20 years ago. But overall, today’s metrics still valorize and reward the qualities Keith embodied—unwavering confidence, unequivocal conclusions, and headline-grabbing pronouncements about human history. Nobody wants to click the headline “Scientists think Neanderthals maybe or possibly made abstract art but are not quite ready to commit to saying it.”

Some 400,000 years ago, the Swanscombe woman had become a fossil, silent and unchanging. But in the 90 years since her remains resurfaced, her perceived place in human evolution has evolved.

In 1935, she sat with Keith in Down House. Now she sits with me in another English scientific institution. Keith saw what he expected to see in this fossil: supposed proof that humanity arose in his homeland. I saw something I was not expecting: the uncomfortable sway that power, politics, and intellectual history have over science. Surely these influences persist, clandestinely clouding my own work. So, what can I learn from the history of the Swanscombe fossil—beyond elucidating her place in our human story?

She taught me that scientists should not aim for unequivocal authority. We should strive for the best possible science—and that entails tentativeness, collaboration, and openness to being wrong.