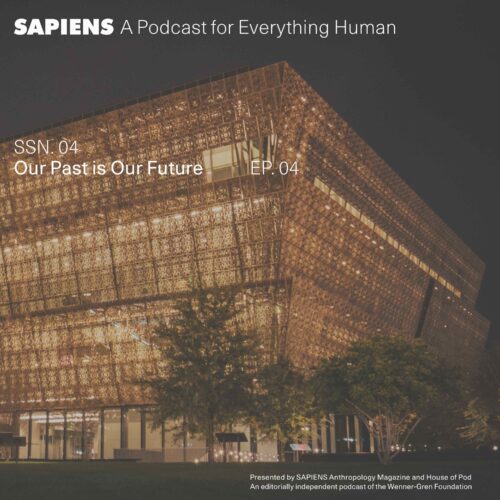

History is taught in all kinds of ways—through textbooks, movies, and … museums. In this episode, museum curators challenge the status quo and connect their ancestry to advance how history is told in cultural institutions. Mary Elliott brings listeners behind the scenes into the Slavery and Freedom exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. And Dr. Sven Haakanson helps re-create an Angyaaq, which is like a kayak, at the Burke Museum in Seattle, Washington.

Guests:

- Mary Elliot is the curator of American slavery at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC). She co-curated the museum’s Slavery and Freedom inaugural exhibition, and she is a team member of the museum’s Slave Wrecks Project. Mary also curated and wrote the special broadsheet section of the award-winning New York Times’ featured publication titled The 1619 Project. She is also the inaugural curator and content developer for the NMAAHC’s digital humanities feature, the Searchable Museum. Mary’s personal research focuses on antebellum slavery, Reconstruction, and African Americans in Indian Territory, with a specific concentration on Black kinship networks, migration, and community development. She’s worked with U.S. representatives on both sides of the aisle in the House and the Senate, and has served as an invited speaker at various academic institutions, including Brown University, Duke University, and universities in Africa, Europe, and the Caribbean. She also has been interviewed by several media outlets and programs—including CBS’ 60 Minutes, C-SPAN, Slate, BBC, NPR, and PBS.

- Sven Haakanson Jr., Ph.D., is Sugpiaq from Old Harbor, Alaska. He is a curator of North American anthropology at the Burke Museum and an associate professor in anthropology at the University of Washington. He is a recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship (2007), the Museums Alaska Award for Excellence (2008), and the ATALM Guardians of Culture and Lifeways Leadership Award (2012), and his work on the Angyaaq led it to be inducted into the Alaska Innovators Hall of Fame (2020). Sven engages communities in cultural revitalization using material reconstruction as a form of scholarship and teaching. His projects have included the reconstruction of full-sized Angyaaq boats from archaeological models and the re-creation of halibut hooks, masks, and paddles. He also has shown the traditional processing of bear gut into waterproof material for clothing. He has collaborated with the community of Akhiok at their Akhiok Kids Camp since 2000.

SAPIENS: A Podcast for Everything Human is produced by House of Pod and supported by the Wenner-Gren Foundation. SAPIENS is also part of the American Anthropological Association Podcast Library. This season was created in collaboration with the Indigenous Archaeology Collective and the Society of Black Archaeologists, with art by Carla Keaton and music from Jobii, _91nova, and Justnormal.

Listen also to SAPIENS Talk Back, a companion series by Cornell University’s RadioCIAMS. In episode 4, we welcome the featured guests of Episode 4 of SAPIENS Season 4: Tiffany Fryer, Cotsen Postdoctoral Fellow in the Princeton University Society of Fellows and a lecturer in Princeton’s Department of Anthropology, and Sven Haakanson, Associate Professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Washington, Curator of Native American Anthropology at the Burke Museum, and a former MacArthur Fellow. This episode was made possible by financial support of the Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology at Brown University and Columbia University’s Center for Archaeology. We want to thank our panelists for leading our conversation today: Erynn Bentley and Ana González San Martín from Brown University. This episode was hosted by CIAMS graduate students Olivia Graves and Henry Ziegler, and the sound engineer was Sam Disotell. SAPIENS Talk Back is produced at Cornell University by Adam Smith with Rebecca Gerdes as the production assistant. Our theme music was composed by Charlee Mandy and performed by Maia Dedrick and Russell Dedrick.

Check out these related resources:

- Slavery and Freedom at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture

- Burke Museum in Seattle, Washington

- From SAPIENS: “How Museums Can Do More Than Just Repatriate Objects”

Episode sponsors:

- Brown University’s Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology & the Ancient World

- Columbia University’s Center for Archaeology

Yoli Ngandali: Museum curators are sometimes thought of as managers and overseers. Their job is to compile and log museum and gallery collections. It’s one of those jobs that seems fancy and sterile from a distance. White gloves and art gallery fancy.

Dr. Ora Marek-Martinez: They are the people behind the scenes sorting through artifacts and deciding what to display. They attempt to bring history and science to life.

Yoli: But what if we understood curators as caretakers and their work or labor as a form of care?

Ora: And what if we remember that our communities and cultures are still alive rather than relegated to the past and can speak for themselves?

Yoli: Hmm. That would definitely change the job role or description.

Ora: Curators have an important role to play in our current society. They interpret cultural objects and produce public-facing exhibitions. They are essentially cultural caretakers of our collective past. In 2016, a U.S. cultural institution was put in place so the stories and objects of the African American community could live on out loud. This was done with the help of these cultural caretakers like Mary Elliott.

Mary Elliott: I am the curator of American slavery at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. I co-curated the Slavery and Freedom exhibition when it opened in 2016.

Yoli: This exhibition is an 18,000-square-foot experience that explores complex stories of both legally free and enslaved African Americans. It begins in 15th-century Africa and Europe.

Mary: We talk about the process of enslaving a person to transatlantic slave trade. We look at the human cost.

Yoli: Then the museum guides visitors through the founding of the United States.

Mary: And we look at all the nation-states that made wealth from all of this and the way governments were invested in this enterprise of slavery. We talk about the diversity of experiences during colonial North America, and we break it down by region because Black people are not monolithic. Where you landed dictated how your life unfolded.

Yoli: And concludes with the nation’s transformation during the Civil War and Reconstruction.

Mary: We make sure that we tell this story through an African American lens that looked out on a world that saw enslaved Black people, free Black people.

Ora: It is an ambitious multimedia exhibition that tells layered stories, and these stories are told from first-person accounts and through powerful belongings and artifacts.

Yoli: And telling the stories of these people and places often requires the creation of new materials. Alongside preserved items from the past in these museum spaces, we encounter interpretive signs, replicas, videos, and statues of historical figures created by the museum for the visitors.

Ora: And the way these materials are created and displayed can really make a difference.

Yoli: For the exhibit, Mary and her team sent the museum artifacts what she calls character studies to help them correctly depict historical figures as statues.

Mary: And we said, “Don’t give us back Thomas Jefferson looking like Superman, with flowing hair, his collar up to his ears in a certain stance.”

Yoli: Despite these instructions, the team initially produced a Thomas Jefferson statue with flowing hair, a collar up to his ears.

Mary: And we told them to change it, and they did.

Yoli: Mary Elliott was unsatisfied with the status quo, which often meant heroic, larger-than-life representations of figures like Jefferson.

Mary: We need him to look like a man that is accessible, so people can think about who he was, who they would be at that time.

Yoli: And it’s not just about what the statue looks like, it’s about how the statue is situated within the larger context of slavery.

Mary: The platform Thomas Jefferson is featured on, I call it the platform of freedom, because behind him are 600 bricks representing the 600 people he owned over his lifetime.

Yoli: The exhibition highlights the hypocrisy of Jefferson.

Mary: You have a president who’s writing the Declaration of Independence, meanwhile, spewing out racist animism about the inferiority of Black people. He just represents a moment for us to really think about the choices that we made at certain points in time and the long-term effects, but also to think about a nation that continually tries to perfect itself and this democracy that we created.

Ora: Another historical figure in the Slavery and Freedom exhibition is Phillis Wheatley, the first African American and second woman to publish a book of poetry. As a young girl in the mid-1700, she was captured in West Africa and enslaved in Boston, Massachusetts.

Mary: There’s a quote from a letter she wrote to a Native American minister during the Revolutionary period. She creates this universal notion of how all of us desire freedom.

Ora: Wheatley wrote, “In every human breast, God has implanted a principle which we call love of freedom; it is impatient of oppression, and pants for deliverance.” But when Phillis Wheatley was cast as a statue for the exhibit—

Mary: They sent us back a woman who was full-figured, with full features, a plain gingham scarf around her shoulders, a plain bonnet. And even though we told them she was frail, petite, sickly, I had to say, “Now you look at this woman you sent me and look at this individual. What you’ve given me is your notion of just Black women. What we’ve asked you for is an individual.”

Ora: Mary Elliott ensured that Phillis Wheatley was not simply a stereotype of a slave.

Yoli: And these are just a few examples of how curators influence the way our stories are told and care-take our collective histories, which is why it’s so important that people like Mary Elliott are working to undermine white supremacy in museums.

Mary: That’s not something that only Black people can do in this type of work, but it is a sensitivity that I hope that closing this gap, there will be more people who can come to the field and raise those issues up and say, “We have to be mindful and intentional when we do this work, because this work represents me, my aunt, my uncle, my cousins.” That’s what that is.

Yoli: This is episode 4: Curating With Care.

Ora: I’m Ora.

Yoli: And I’m Yoli. In this season on the SAPIENS podcast, we explore how Black and Indigenous archaeologists are changing the stories we tell.

[SAPIENS introduction and music]

Ora: Before becoming a curator at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, Mary Elliott had been tracing her own family’s story.

Mary: I was doing family history research for years. I’ve been doing it since the 1980s.

Ora: She learned that she was a descendant of community leaders.

Mary: My uncle and my great-grandfather had a chain of department stores, a hotel, a theater, a bank, and they used groups like the 20 Gents to serve the community, so they would invite the children in the community to come to the theater, and they’d give them bags with oranges and dimes. And they built churches, and they built schools.

Ora: They were deeply invested in the well-being of others, which inspired Mary.

Mary: They understood the meaning of community and the sense that what happens to the least of us affects all of us. It’s not just an African American thing, that’s a human thing, but it is a tradition in the Black community because we had to look out for each other.

Yoli: And after months at the Library of Congress, among the elaborate arches and millions of books, Mary uncovered a new detail.

Mary: It turns out my family had ties to Booker T. Washington and the National Negro Business League.

Ora: She began to make connections and outline her family’s history through slavery, abolition, and beyond.

Mary: So, my family was enslaved in South Carolina and carried to Mississippi. They gained their freedom after emancipation came, fought for their right to vote, hold office, raise a family, got into a confrontation with the Klan. It didn’t work out well for the Klan. The family left, went to Indian Territory, which was seemingly a frontier for freedom, even though the Klan was there, even though there was racism even between Native Americans and African Americans and alliances as well. But the family was able to establish several businesses. They were members of the Executive Committee of the National Negro Business League, but most importantly, they used their economic and political power to lift up the Black community.

Yoli: Mary spent years doing this research and telling this newly learned oral history to her family. This wasn’t even Mary’s job.

Mary: My mother saw me doing all this family history research. She said, “No, I think this is your passion.”

Yoli: But, the next thing Mary knew, her mother was outlining an itinerary of destinations for Mary.

Mary: “You’re going to Oklahoma. I bought you a ticket. You’re going to Mississippi, you’re going to Virginia, you’re going to South Carolina.” So, she really is the person who sent me all over to bring together these pieces of history and start to bring the family history into focus.

Yoli: What started for Mary as a break from law school became so much more: a moment of transformation and the start of a new career path.

Mary: I did not have museums on my radar, but it was my mother who saw my passion and saw how I doggedly pursued this history and how I recounted the history in a way that actually impacted people. And I’m very grateful for my mother because people say, “How are you able to pursue your passion?” And the truth be told, I didn’t know this was my passion. But she did, and she knew it because I would have done this for free. She knew it because I was already doing it for free for me. And for my family. And when I would tell people their history, they would get excited by it. And it’s because of her that I ended up doing what I’m doing.

Ora: For her, being a museum curator has everything to do with being her mother’s daughter and being the great-grandchild of a Black man who built schools and churches and cared for children in their community.

Yoli: Like Mary Elliott, Dr. Sven Haakanson has personal ties to the stories he is telling.

Dr. Sven Haakanson: Working in museums and doing archaeology is a way for us to show our deep and rich history and connection to the lands that we are from and the ocean that we are beside.

Yoli: For one, Sven, is a curator of arts and culture at the Burke Museum of Nature and Culture in Seattle, Washington.

Sven: I’m originally from the village of Old Harbor on Kodiak Island.

Yoli: But unlike Mary, Sven was trained as an archaeologist.

Ora: Sven received a MacArthur Genius Award, but more importantly, Sven is part of the Alutiiq or Sugpiaq, which is used more often today, from an Alaskan Native village situated on the island of Kodiak. Like many Indigenous languages, Alutiiq has been systematically erased and replaced by colonial languages.

Sven: In Kodiak alone, there’s only 15 fluent speakers living, once where there were 30,000 or more. I feel so grateful to my mom because she is one of the 15 fluent living speakers left in my language and having to be able to talk with her to visit with her, to ask her questions. You know, so I’ve been recording, I’ve been writing down as much as I can when I do talk with her and hopefully have that record for the future.

Sven’s mother: [Speaking Alutiiq, “Sister sun brother moon”]

Sven: As I’ve been working with my mom and translating some early historical accounts and historical texts like, for example, Alphonse Pinart’s journals, and that’s translated as “The Moon is a man, and the Sun is a woman.”

Sven’s mother: [Speaking Alutiiq]

Sven: “The woman is strong.”

Ora: Translating Alutiiq from Alutiiq perspectives and places is essential to reclaiming the language and rewriting the stories told by settlers.

Sven: For example, in this one context, the person who wrote the word down was saying, “Well, they are looking for devil helpers.” And when I read that, I read it as: “They were looking for spirit helpers.” But if I translated it literally, this is in Russian, if I translated it literally, it would completely denigrate the entire text that I had been translating to being something about evil, something that was horrible Awa’uq [to be numb] and how we see our world today, as opposed to, they were looking for helper spirits in what they were doing.

Yoli: And like Mary Elliott, Sven’s professional work as an archaeologist and curator is rooted in his family and community.

Sven: I feel very lucky to have grown up in a village of less than 200 people and, you know, where everybody knew your business, and everybody’s business was yours. So, you looked out for each other. I grew up fishing, grew up working with my hands. I spent 20 years of my own life every summer out salmon fishing. So, you know, learning what real hard work is. And, you know, I think that was really transformational in terms of the work I do now.

Ora: Connecting his tight-knit community to their long lineage and shared heritage is part of what Sven hopes to offer.

Sven: Even in my own lifetime. We didn’t realize that our ancestors had lived on Kodiak for over 7,500 years. It has only been in the last 20 years that our community has fully grown to not only understand but know about our rich and deep cultural history. So, it’s a more recent thing as we have become more aware of how powerful and important knowing our history is for all of us.

Ora: To help make the stories of his people and their legacy more wide-reaching and accessible, he pursued a career in archaeology, particularly ethno-archaeology.

Sven: Ethno-archaeology is working with a living group and understanding the dynamics of how sites were used and then, eventually, how sites are abandoned.

Yoli: Ethno-archaeology takes seriously the voices and insights of current communities instead of relying on historic secondhand sources like missionaries or “explorers.” This subfield of archaeology allows us to hear directly from Indigenous people about their traditions and decisions. And this helps archaeologists really understand a little bit more about material culture presently and to be able to infer that into the past.

Sven: It gives us a snapshot of an invisible life that is impossible to see archaeologically.

Yoli: One of Sven’s first experiences in the field was with the Nenets, where he worked with the community in the Russian far north. Here, he practiced integrating his values with the training he received as an archaeologist.

Sven: I had the privilege of being given over 400 rolls of film from National Geographic, and so, I was able to document their campsites, what they were doing ad nauseum. But before I even did that, I asked for permission to photograph. I just didn’t assume I could do that. So, coming from my perspective as a Native, I stepped back and said, “OK in Kodiak, where I grew up, because we are not living as we did in the past today, what would I love now to have photographs of my community?” And so I thought about when I was photographing the Nenets, is: What would they want to have in 100 years that most people would overlook? What kind of photographs, what kind of information would be useful for them?

Yoli: Sven realized that as a Native archaeologist, he brought a unique lens and a respect for other Native cultures and peoples. He was able to partner with the Nenets while paying careful attention to their protocols and priorities.

Sven: So, I photographed, even of the most mundane things of, how were they processing the wood for making fires, to what were they doing as they processed the reindeer to prepare it to use the skins, to eat, to process, you know, the stomach? So, I tried to document all of that so that there’s a record of it, even if I can’t analyze or understand what I was seeing. I tried to document that, but I would ask their permission first before I did any of that. I mean, and at a point they were like, “OK, it’s OK for you not to ask this, you know, take your pictures, and it’s OK.” But I was trying to be as respectful as possible because growing up, we’d have people come in and just take pictures as if they owned us. And I didn’t approach my work that way.

Ora: Sven’s life experience led him to participate differently, not pretending to be something he was not, but instead doing what he loves with who he loves, which led Sven to archaeology working with Natives as a Native. Sven later found out that he was only originally authorized to spend a week with the Nenet people, but they allowed him to stay for an entire year.

Sven: And I said, “Oh, why?” And this is all in Russian, broken Russian, and Nenets. And he’s like, “Well, you were willing to help chop wood, haul water, and do things that a lot of the outsiders wouldn’t do.” And to me, I didn’t think about that because that’s what you do. When you’re in a small community, you help each other.

Yoli: After his ethno-archaeological research alongside the Nenets, Sven eventually made his way into museums. He spent 13 years as the executive director of the Alutiiq Museum in Kodiak, Alaska, before working as an associate professor at the University of Washington and as a curator of North American anthropology with the Burke Museum.

Ora: And at the Burke Museum in Seattle, Washington, Sven took on a powerful reclamation project. He utilized his position as a curator to tap into something big.

Sven: Being a curator and having full access to the collections, they have one of only 15 model Angyaaqs from my tribe in the world. And so, using my position, I was able to examine, photograph, draw, and literally reverse engineer this model.

Ora: The Angyaaq is an open boat, like a kayak. And as a curator, Sven had access to a model of these ancestral Angyaaqs, but no full-size boats had existed for decades.

Sven: So, now we have this knowledge that disappeared, literally disappeared from the community by the 1860s from Kodiak being used again because of museum collections.

Ora: And not only did he bring the Angyaaq back to life through the tools and resources of the museum, but he also brought this knowledge home.

Sven: In 2014, I worked to make kits. I went back to the village of Akhiok, and through the kid’s camp, we made 13 model Angyaaqs. It was the first time in over 150 years model Angyaaqs were made on Kodiak. And so, to be part of that, to see that in use, it’s one of those moments in time where you realize, like: Yes, this works, and it really can transform a community to not only understand their rich history but understand how amazing their ancestors were.

Ora: As for Sven, this is a pathway of reclamation, a way to put museum collections to work on the ground and in the water.

Sven: It was a real privilege building a trusting relationship between a museum and a community so that we can share this knowledge once again within our own community.

Yoli: Some curators like Sven Haakanson are trained as archaeologists. Others, like Mary Elliott, are historians, and the beauty of storytelling is that it can be told in many forms and from many perspectives.

Ora: Museums are facing increasing scrutiny for questionable practices, such as featuring items that have been stolen through pillaging or removing objects from communities by force.

Yoli: And yet, Mary Elliott and Dr. Sven Haakanson navigate their roles and subvert the system on behalf of Black and Indigenous communities. They work to liberate the stories that these belongings and cultural remnants tell about our histories.

Ora: After over 30 years of working in museums, Sven is clear about what museums have been and what they could be.

Sven: Museums originally were the idea behind, “Oh, let’s preserve these cultures because they’re disappearing.” Well, we’re still here. Yes, our cultures have changed because we have been forced to forget and have it erased through these colonial practices of suppression and, you know, “save the man, destroy the Indian” mentality. How do we make sure that our communities have access to this knowledge that was taken from our communities, whether it was sold or whether it was actually stripped or stolen? How do we provide access to these collections? How do we provide access to this knowledge?

Yoli: Mary Elliott is also paying close attention to how the Slavery and Freedom exhibit is affecting her community and the general public.

Mary: If you ask me what my favorite object is, I cannot tell you that I have a favorite object. But if you ask me what my favorite thing is about the exhibition, it is seeing the diverse audience come into the exhibition, read the labels together, and say to one another, “How come I didn’t learn this in school?” And actually be moved by the exhibit. It’s so powerful to see that.

Yoli: And this is so exciting because museum professionals warned Mary that there was too much interpretive information and that people wouldn’t take the time to read and reflect. But Mary knew better.

Mary: People have called me from the exhibition and said, “I’m still down here after three hours because when they walk through the exhibition, it’s like being in a book club.” Black, White, young, old, short, tall, fat, skinny, you name it, they’re all in there, and they’re all reading the history, and they’re looking at these authentic artifacts that tell the story of the nation and of humanity. That’s what I love most.

Ora: Sven and Mary are curators of a different kind. They play by another rulebook and prioritize reclamation and education. They are creative caretakers of our cultures. Because of the spiritual and sacred nature of ancestral belongings, Indigenous peoples often engage protocols to ensure proper respect and care for their cultural heritage and futures.

Sven: So, one of the things that I feel very adamant about is, alright, if we are going to talk about decolonizing these museums or changing the museum practices, what do we need to do, not only in our own practice but for each other? And that’s where you start to get into, OK, how do we learn not only about the cultural piece, but how do we start to learn about the cultural context of the piece? But how do we learn about the protocols in how we can share that piece with the communities?

Ora: Protocols are a word we use to describe the self-defined parameters and practices that Indigenous communities engage in to invoke relationality and to ensure that sacred responsibilities are upheld. This ensures a supportive and accountable relationship with one another and with outsiders.

Yoli: And we hold ourselves accountable through a relationship that respects the protocols of each community. Both Sven and Mary are attentive to ways that they are curators. Museums as institutions can be anchored in relational ethic. And here are some of the ways that they ground and guide their work.

Mary: It’s one thing to know your genealogy. So, one thing to know your family’s story about a place. It’s another thing to understand why people move left instead of right.

Sven: What does a community want to share about that piece and not hear your interpretation?

Mary: How do we help descendants understand the important role they play but also find pride in their story? And then also to bring community voices to the public so people can hear from first-person voices, not just ours, the museum professionals and practitioners.

Yoli: And when designing the exhibit, making sure that the community is centered.

Sven: So, when you go into the new Burke, what we did is we designed the exhibit text so that we use the language in the name of the cultural piece first, and then we have our English translation.

Ora: Confronting these stories means wrestling with our shared stories and allowing community members to join in that process.

Mary: My notion is always like, there’s human suffering, but there’s the power of the human spirit. Even the ones who didn’t make it. How proud am I that they existed, that they existed and lived, endured this, and I was able to be here.

Yoli: And it means confronting the power and a legacy in which museums have done and continue to do harm toward Black and Indigenous communities.

Sven: One of the things that I’ve run into is not people resisting, but people being afraid, afraid of saying the wrong thing or making a mistake in terms of what they’re doing because they want to do right. And that’s a lot of work when you have to be very self-reflective, and honestly, it’s uncomfortable for all of us. And I think even more uncomfortable for the people who have been in the power, colonizing or taking over these other communities for their own gain. And when you’re working with the culture pieces, whether you’re Native or not, you’re the caretakers of our histories. You’re the caretaker of our knowledge. And the collections that you have are really important. It might seem simple or mundane to have a basket, but in that basket, you’ve got a history of not only the maker but the family and the community and the culture that’s embodied within that piece.

Ora: Curators are more than storytellers. They are caretakers, and they have big responsibilities to the visitors of the museums, the communities whose belongings are now owned by museums, and to their own process of changing the status quo.

Yoli: And it requires many strategies. Mary Elliott believes in the importance of closing the gap in terms of Black curators and archaeologists of the future.

Mary: But particularly young people, to think about what opportunities are there to do conservation work, to do oral history work, to consider working in archaeology, anthropology, to consider doing research. So, that’s always in the forefront of my mind. How to close the gap so that there are more people of color in these fields. And then to see people creating opportunities for the next generation, growing the next generation of archaeologists of color. And I’ve told them, “You don’t even know right now the work that you’re doing, the ripple effect it’s going to have for generations to come.”

Ora: And Sven reminds us about the potential and power of decolonization, more than just being a trendy word, by building relationships and dismantling the colonial structures.

Sven: In a way it’s like, “OK, I’ve decolonized. Check that box. Move on.” Actually, it’s how do we change our practices and what we do moving forward? You know, it’s about having a deeper understanding of each other and the challenges that people of color have faced for generations. So, I guess I mean, I use “decolonize,” but I also struggle with that term because, how do you decolonize a system without completely destroying it? How do you change the practices without having the people who are doing those practices question what they’ve been inculcated into, what they’ve been taught to do without thinking about, to change? But, you know, the future archaeology has changed and is changing in ways that I think, if done right, can be really enriching for both the archaeologists and the communities. So, building relationships and finding ways to engage together and collaborate together, not just go and consult. So, providing opportunities for community members to come in to these collections to not only learn about the collections, but to be able to take that knowledge back home with them and share it with their community or share it with their family in order to create new stories.

Ora: This episode is dedicated to Sven’s mother, Mary, who transitioned in the months after we recorded our interview with Sven.

Yoli: This episode of SAPIENS was hosted by me, Yoli Ngandali.

Ora: And me, Ora Marek-Martinez. SAPIENS is produced by House of Pod. Jeanette Harris-Courts is our lead producer, alongside producer Juliette Luini and story editor Rebecca Mendoza Nunziato. Jason Paton is our audio editor and sound designer, and Cat Jaffee and Dr. Chip Colwell are our executive producers.

SAPIENS is an editorially independent podcast funded by the Wenner-Gren Foundation, which has provided vital support. Our thanks to Dr. Danilyn Rutherford, Maugha Kenny, and their staff, board, and advisory council. This season was also created in collaboration with the Indigenous Archaeology Collective and Society of Black Archaeologists, with special help from our advisers Dr. Sara Gonzalez, Justin Dunnavant, and Ayana Flewellen.

Yoli: This episode was made possible by our guests, Sven and Mary, as well as the generous financial support of Brown University’s Joukowski Institute of Archaeology and Columbia University’s Center for Archaeology. Additional funding for this series was provided by our friends at the Imago Mundi Fund at Foundation for the Carolinas. Thanks always to Christine Weeber and everyone at SAPIENS.org. Please be sure to visit the magazine for the newest stories about the human experience.

Ora: SAPIENS is part of the American Anthropological Association Podcast Library. For more information, visit SAPIENS.org and check out the additional resources we offer in the show notes on our website or wherever you’re listening to this podcast.

Yoli: And did you know that the Archaeological Center’s coalition is partnering with us to go deeper on what you just heard with companion episodes? You can find these extended discussions with academics and students about reshaping archaeological practice on their website and any podcatcher by searching for Cornell University’s Radio CIAMS. That’s radio C-I-A-M-S.