Milpa is an ancestral way of farming in Mexico and other regions of Mesoamerica that involves growing an assortment of different crops in a single area without synthetic pesticides and fertilizers. This provides people in the region with a wide variety of foods and a balance of nutrients. In recent years, with the introduction of farming based on synthetic herbicides, milpa has changed, and land is used to grow just a single crop. This change in agriculture has led to the rise of ultra-processed foods in these rural areas, which is impacting the nutritional health of the people. This change in agriculture, together with the rise of ultra-processed foods in these rural areas, is affecting the nutritional health of the people.

In this episode, bioanthropologist Anahí Ruderman shares her experiences working with a milpa growing community in Veracruz, Mexico, that is resisting the food of globalization as it tries to cook up a healthier future.

Anahí Ruderman is an Argentinean biological anthropologist with a Ph.D. in biological sciences from the Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina. She is currently an associate researcher at the Instituto Patagónico de Ciencias Sociales y Humanas of the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas of Argentina. Anahí is interested in processes related to the nutritional status and diet of contemporary populations in Latin America in the context of globalization and food transitions. She uses analytical tools from different disciplines that range from human evolutionary biology, population genetics, and human ecology to history and sociopolitics.

Check out these related resources:

- Mano Vuelta Project YouTube Channel

- La Milpa: Government of Mexico Website

- “Asociación entre seguridad alimentaria, indicadores de estado nutricional y de salud en poblaciones de Latinoamérica: una revisión de la literatura 2011–2021” (“Association between Food Security, Nutritional Status, and Health Indicators in Latin American Populations: A Literature Review (2011–2021)”)

- Repository of Scientific Publications of the Project

SAPIENS: A Podcast for Everything Human is produced by Written In Air. The executive producers are Dennis Funk and Chip Colwell. This season’s host is Eshe Lewis, who is also the director of the SAPIENS Public Scholars Training Fellowship program. Production and mix support are provided by Rebecca Nolan. Christine Weeber is the copy editor.

SAPIENS is an editorially independent magazine of the Wenner-Gren Foundation and the University of Chicago Press. SAPIENS: A Podcast for Everything Human is part of the American Anthropological Association Podcast Library.

This episode is part of the SAPIENS Public Scholars Training Fellowship program, which provides in-depth training for anthropologists in the craft of science communication and public scholarship, funded with the support of a three-year grant from the John Templeton Foundation.

Milpa for the Future

Eshe Lewis: What makes us human?

Anahí Ruderman: Truly beautiful landscapes.

Nicole van Zyl: The roads that I used every day.

Thayer Hastings: Campus encampments.

T. Yejoo Kim: Eerie sounds in the sky.

Eshe: What makes us human?

Cecilia Padilla-Iglesias: Division of labor.

Charlotte Williams: Colonialism.

Giselle Figueroa de la Ossa: The value of gold.

Dozandri Mendoza: Fun. Dance.

Justin Lee Haruyama: Cultural and social interactions.

Luis Alfredo Briceño González: Hopes for a better future.

Eshe: Let’s find out! SAPIENS: A Podcast for Everything Human.

[INTRO ENDS]

Eshe Lewis: In rural Mexico, globalization is introducing processed foods and genetically modified crops to people who have historically relied on local agriculture. These challenges are altering farming practices, affecting diets, and impacting the health of young people in these areas.

In today’s episode, I’m speaking with Argentinean bio-anthropologist Anahí Ruderman. She has been part of a project that is researching the dietary changes of a farming community in Veracruz, Mexico. Anahí told me about how community strategies are working to address the negative effects of globalization in hopes of keeping the community healthy.

Eshe: Hi, Anahí.

Anahí Ruderman: Hi, Eshe.

Eshe: Can you please introduce yourself and tell me a bit about your research?

Anahí: My name is Anahí Ruderman. I’m a biologist. But I’ve always been interested in human biology and anthropology. I am from Argentina, specifically from the province of Cordoba that is in the center of the country. But I’ve been living in the city called Puerto Madryn in the Patagonia region of the country for the last nine years.

Eshe: OK. Can you tell us where you are working at the moment and what kind of position you have?

Anahí: I am an associate researcher at the Patagonian Institute of Social and Human Sciences that belongs to CONICET. It’s the acronym in Spanish for the National Council of Scientific and Technical Research. I did my Ph.D. and my postdoctoral research at that institute. And right now, I am waiting for the result of a competition for a permanent research position at CONICET, but as you might know, with the current national government making big cuts in scientific research budget, I have no confidence with the results.

I recommend you to listen to the last season episode of the podcast produced by Pia Tavella called “When Scientists Take to the Streets,” if you wanna have more information regarding the situation.

Eshe: Yeah, Pia gave us a great story about how difficult it is for Argentine researchers right now. I am hoping, and I think our listeners are hoping too, that you get good results and hopefully, you land a position, but we also understand how difficult that environment is right now.

Could we talk a bit about your research? I would love to know more about the research topics you study and why you find them so interesting.

Anahí: Yeah, during my Ph.D., I did research in population genetics, specifically related to complex traits and diseases. But when I was finishing my Ph.D., I realized that I wanted to have the experience of working in a different area. So, I’ve always been interested in everything that has to do with food and nutrition, and it was particularly relevant for me to look and address nutrition in food-producing populations.

So my advisor put me in touch with a Mexican researcher, Alejandra Nuñez de la Mora. She’s researching the impact of agricultural practices on food security, human ecology, and maternal and child health in rural communities in Veracruz, Mexico. And she invited me to participate in this amazing project called Mano Vuelta.

Eshe: OK. Can I ask for some more information about the Mano Vuelta project? And maybe how you contributed to it?

Anahí: Yeah, so in April of 2023, I won a scholarship and I went to Veracruz. I stayed until July in a small town called Coatepec that completely captivated me, by the way. And as a member of the project’s community health team, I took anthropometric measurements, that is weight, height, and mid-arm circumference of the children and adolescents attending schools in rural communities that are involved in the project. And I also conducted interviews with the women in the communities, asking questions about their diets and about their food and water security.

The region of impact of this project is the national park called Cofre de Perote. It is located at the center of the state of Veracruz. The state of Veracruz is at the center of the country. And this region includes three watersheds that are really important because they supply water to the main cities in the area. For example, Xalapa, that is the capital city of the state of Veracruz.

It also has the best-preserved remains of mesophilic forest in the region, and it’s a mountainous area with truly beautiful landscapes and vegetation. So in this place, there are several rural communities of milpa farmers.

Eshe: OK. I’ve heard you say this word milpa. Can you explain exactly what that is or what it means?

Anahí: Milpa is an ancient crop that grows in different regions of Mesoamerica. In Mexico, it has a strong presence and roots. But I think we should get a firsthand description of what milpa is and what it means to the rural communities of Cofre de Perote from Pamela Ruiz Ponce.

Pamela Ruiz Ponce: Yo soy coordinadora de incidencia del proyecto “Biodiversidad en la milpa y sus suelos. Bases para la seguridad alimentaria de mujeres niñas niños rurales del Cofre de Perote”, también conocido de cariño como Mano Vuelta.

La milpa es un sistema ancestral. Hay muchos tipos de milpa y en concreto esta milpa de la que estamos hablando aquí en las faldas del Cofre de Perote es una milpa que es como de montaña, Que involucran no nada más que los componentes agrícolas, como sería el maíz, eh, distintos tipos de frijoles, calabazas, verdad? Que son plantas cultivadas en las cuales, pues, se sustenta la alimentación, pero que se complementan con otros componentes, por ejemplo, árboles frutales, también algunas especies no cultivadas que crecen solas en la milpa, como los quelites, algunos hongos, y están muy asociadas a la parte forestal, que las familias van sabiendo aprovechar en sus diferentes temporalidades, ¿no?

Pamela Ruiz Ponce (English Dubbing): I am the advocacy coordinator for the project “Biodiversity of the Milpa and its Soils, Basis for Food Security for Rural Women and Children of Cofre de Perote.” Also affectionately known as Mano Vuelta.

The milpa is an ancient system. There are many types of milpa, and the one we are talking about here on the slopes of Cofre de Perote is a mountain milpa. It’s not just agricultural components like corn, different types of beans, and squash. These are cultivated plants that provide food. But they are complemented by other components, for example, fruit trees, some mushrooms, also some noncultivated species that grow alone in the milpa, such as quelites, and they are closely related to the forestry part, which the families know how to take advantage of in their different seasons.

Anahí: I also asked Pamela about the nutritional value of Milpa.

Pamela: Pues una milpa que es diversificada ofrece gran diversidad de nutrientes para las familias que las cultivan, tales como carbohidratos, proteínas, vitaminas. En Mano Vuelta, desde la investigación que se hizo en las comunidades y con las variedades de Maíces y frijoles, encontramos que la diversidad de variedades ofrece distintos nutrientes. Esto no quiere decir que haya alguna variedad mejor que otra. Sino que los nutrientes que no ofrece, por ejemplo, el frijol gordo, si te los va a dar el ayocote. El ayocote es una variedad de frijol que es una especie distinta.

Además, las milpas diversificadas que tienen un manejo agroecológico, es decir, que se cultivan sin ningún tipo de agroquímico o herbicida pues permiten que diversidad de quelites, como les llamamos aquí en México, o plantas que no se cultivan pero que nacen en la milpa, pues nazca ahí. Todos estos quelites hay diversas investigaciones que demuestran que ofrecen una gran calidad de antioxidantes, de vitaminas y de minerales que por sí solos, los granos básicos no nos dan.

Pamela (English Dubbing): A diversified milpa offers a great variety of nutrients to the families that cultivate it, such as carbohydrates, proteins, vitamins. At Mano Vuelta, we have found through research in the communities and with the varieties of corn and beans that the diversity of varieties provides different nutrients. This is not to say that one variety is better than another. But the nutrients that the big bean does not provide, the ayocote will. Ayocote is a variety of bean that is a different species.

In addition, diversified milpas that are agroecologically managed, meaning they are grown without any type of agrochemical or herbicide, allow the diversity of quelites to grow there. Quelites, as we call them here in Mexico, are plants that are not cultivated but grow in the milpa. There are several studies that show that all of these quelites provide a high quality of antioxidants, vitamins, and minerals that basic grains alone do not provide.

Eshe: What happened to milpa? Is this still a part of people’s diet and farming practices in this community now?

Anahí: Yeah, they grow milpa, but it is a different milpa. It has less variety of vegetables. They usually grow corn and beans, but they are not cultivating the other vegetables that they used to be part of the milpa. So it is, it’s a process that is going to a kind of monocultivo or dicultivo.

Eshe: Like a monoculture, or I guess in the second case, it would be biculture, right? So the idea that you’re only growing one or two crops as opposed to what it sounds like what you’re describing before, which would have been, a very varied number of crops, right? Whether it was different kinds of beans or corn or just other vegetables or tubers.

Do you have any sense of what’s causing the decline in other crops from the milpa?

Anahí: Changes in agricultural practices bringing in modern practices like the use of herbicides. Herbicides don’t allow other vegetables to grow except transgenic corn. So they maximized their crops, but it affected the crops and the community and the health of the people in different ways. This is happening not only in the rural communities of Cofre de Perote but in much of Mexico.

Eshe: So, you went to Cofre de Perote and met the communities and did your work there. Are there any experiences that you feel really capture the spirit of this project?

Anahí: Yeah. One day we went to a community called El Zapotal. There I met Jorge David Perez Iriarte. He had been a teacher at the community’s only school for more than 15 years.

Jorge David Perez Iriarte: Yo me llamo Jorge David Pérez Iriarte.

Anahí: When I first met Jorge, I recognized him as someone who was really committed to the health and well-being of his students.

Eshe: Why do you see him as someone who is so dedicated to his students?

Anahí: When we went to the school in Zapotal, the first thing we did was talk to Jorge, and we immediately felt that he was very excited to have us there. He said that the children in the community don’t have the opportunity to meet many people outside the community. So that was my first impression when we met Jorge.

He was very happy that we were there and that we could share with the children. This gave me the feeling that Jorge was really involved in the learning process and the development of his students. Jorge told us that a few years ago, Zapotal was a very isolated community that received little government assistance, leaving the community behind in terms of access to services.

Jorge: Era una escuela en una localidad muy cerca a Xalapa, pero que parecía que el tiempo se había detenido y que se encontraba allá en la lejanía y no solo en una distancia de tiempo y perdón de kilómetros y horas, sino también de tiempo no?. Porque realmente había una situación complicada respecto a muchísimos temas, sobre todo de servicios. Y pues me encuentro con paisajes hermosos, con una vegetación, eh, tremenda. Con el sol cerca acariciándote con la montaña. Ahí no? Esteh, brindándote frío y lluvia y neblina.

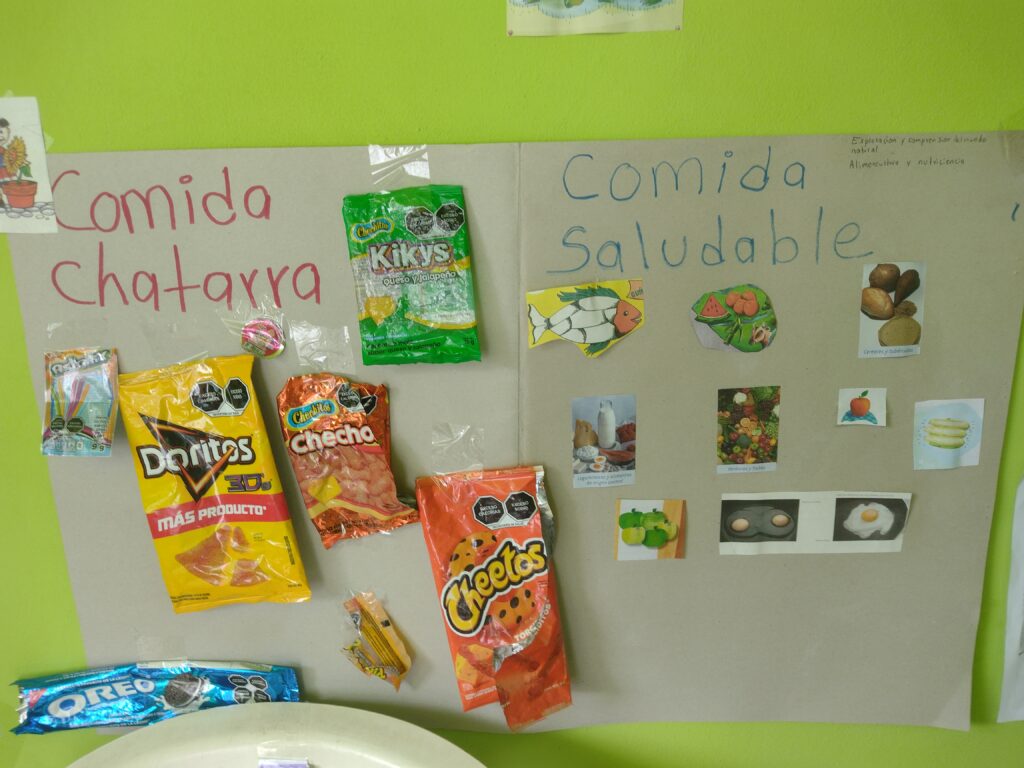

Cuando empieza a visibilizarse el Zapotal, cuando empieza a ser un foco de interés, no? Para algunas asociaciones para algunos grupos, la misma Universidad Veracruzana, pues también hubo otro punto en el que pasamos de una tienda con productos básicos a tres, cuatro tiendas y ya no con productos tan básicos ya más bien con, con una oferta alimenticia diferente, eh? Muy atractiva para los pequeños. Entonces, cuando tú logras que los productos se vendan, permíteme decirlo así es como una suerte de globalización, ¿no? Esteh, pues la oferta crece y el mercado crece y la demanda crece. Y pues se da que los niños empiezan a consumir más cosas. ¿No?

Jorge (English Dubbing): It was a school in a community very close to Xalapa, but it seemed like time had stopped, and it was far away, not only miles and hours away, but also time, right? Because there was a really complicated situation with many issues, especially services. And I find myself with beautiful landscapes, with enormous vegetation, with the sun close to caress you, with the mountain giving you cold, rain, and fog.

When El Zapotal began to gain visibility, when it began to be a focus of interest for some organizations, some groups, also the Universidad Veracruzana, there was a point where we went from one store with basic products to three, four stores, and no longer with basic products, but with a different food offering that was very attractive to children. So, in terms of globalization, if you manage to sell your products, well, the supply grows, and the market grows, and the demand grows, and it turns out that children start to consume more things, right?

Anahí: In other words, an unfavorable process occurs in which new foods enter the diet of the community, but not necessarily healthy food. Nevertheless, Jorge had the will and the initiative to work with the community to promote the consumption of local and healthy foods.

Jorge: Yo les decía “cuando yo llegué a mi me dijeron que aquí no se daba nada más que maíz. Maíz y frijol y chile”. Y ahora resulta, les decía yo ¿no? hace algunos años, que sí se da, se da jitomate, se da ciruela, se da esteh, hay una tipo de calabaza muy grande que se llama chilacayote que es muy, muy grande. Entonces les digo, “bueno, vamos a aprovechar todo esto que sí se da, berenjena”.

Y empezamos a hacer un consumo cercano a las cosas que sí tenemos. Que no nos cuestan caras porque las tenemos ahí, pero que no son tan populares, por decirlo así, en cuanto a la siembra y la cosecha. Y también fue otra parte del aprendizaje muy importante ya recientemente del proceso en Zapotal, el decir bueno, vamos a consumir lo que tenemos y vamos a comprar lo que sea barato por las temporadas, ¿no?. Y eso se empezó a hacer también.

Jorge (English Dubbing): I told them, when I first arrived, some people told me that nothing was grown here but corn, beans, and chili. And now it turns out, I told them a few years ago, that tomatoes and plums also grow here, and also there is a kind of very big pumpkin called chilacayote So, I tell them, “Well, let’s take advantage of all these vegetables that also grow.” And we start consuming things that are close to what we have that don’t cost us much because we have them, but are not as popular.

It was also another very important part of the learning process, recently in Zapotal. To say, “Well, we are going to consume what we have, and we are going to buy what is cheaper in season,” right? And that started to happen.

Anahí: After hearing these stories from Jorge, I understood that he had been a key player in the life of this community for many years, and that food was a fundamental aspect for him. He also noticed that there were some cooking practices that could be improved also.

Jorge: Cogíamos, nosotros decimos “antojitos” a este alimento hecho con maíz, ¿no?, la cantidad de aceite que te quedaba en los dedos era suficiente como para limpiar 10 pares de zapatos y dejarlos lustrosos. Y entonces, platicábamos con mi otro compañero y yo decía, “es que en algún punto esto les va a hacer daño”.

Jorge (English Dubbing): We would grab, we call them “antojitos” to these foods made with corn, right? The amount of oil left on your fingers was enough to clean 10 pairs of shoes and leave them shiny. And then I would talk to my colleague, and I would tell him, “At some point, this is going to be bad for their health.”

Eshe: Coming up after the break, we hear more from Anahí, and Jorge describes how he started to create healthier diets for his students.

[BREAK]

Eshe: Welcome back. Before the break, we were hearing about a teacher in a small town in Veracruz, Mexico, who was pushing back against the processed foods entering his rural community. Let’s pick up our interview Anahí Ruderman.

You mentioned that Jorge was concerned. He wanted to figure out how to improve some of the eating habits of the community. Could you say a bit more about that?

Anahí: I think Jorge knew that in order to improve certain nutritional practices, it was better to work as a team and that this work should be intergenerational and that the mothers should be actively involved in the process.

Jorge: Las mamás se juntaban por equipos y se asignaba un día a cada equipo para que ese día ofreciera el alimento a la hora del descanso. Las otras mamás aportaban una cuota con la que se juntaba una cantidad para comprar, eh, lo que se iba a dar de comer. Y empezamos a intentar que la dieta que se daba en la escuela, pues tuviera las características de ser una dieta balanceada, variada, ¿no? Y suficiente.

Jorge (English Dubbing): The mothers were grouped into teams, and each team was assigned a day to provide food during the lunch break at school. The other mothers contributed a fee, which was used to raise the amount needed to buy the food they would provide. And we began to try to make sure that the food served in the school had the characteristics of a balanced, varied, and sufficient diet.

Eshe: OK. This sounds like a great initiative, and I can understand how adults might get on board with this, but I am really curious to know about the reaction of children in school to this new plan that they were rolling out. Can you tell me what kids thought about this?

Anahí: Yes, it seems that Jorge struggled to get started this project at first, but with patience and persistence, I think he began to see some results. One of the things we talked about with Jorge was how these experiences don’t seem to bear immediate fruit. But I think he’s confident that they will have an impact in the future generations.

Jorge: Con los niños, la situación era de que si no estaba dulce, no estaba bueno. Ellos tienen una palabrita que todavía cuando escuchen, se van a reír. Dicen “esto está desabrido”. Desabrido quiere decir que está simple. Quiere decir que está feo, que no está bueno. Entonces no, yo choqué con pared, no comían. Se quedaba la comida.

Jorge (English Dubbing): When it came to children, if it wasn’t sweet, it wasn’t good. They have a little word that they laugh at when they hear it: “This is flavorless.” Flavorless means it’s simple, it means it’s ugly, it’s not good.

So I hit a wall, they didn’t eat, the food stayed.

Anahí: So, one thing that really stuck with me was the importance Jorge gives to intergenerational communication. He talks about how the information given to the children in the classroom, such as the nutritional value of the products they consumed, clashed with what the children experienced in their homes on a daily basis.

And Jorge said that when everyone was present in the process of making food, things began to change for the better.

Jorge: Se tienen que juntar niños y niñas y sus madres que cocinan con la misma información para que entonces todos sepamos qué vamos a comer y por qué lo vamos a comer. Y cuando hacíamos los menús, los niños dicen “¿podemos comer enfrijoladas?” Sale, las ponemos, enfrijoladas. Empezamos, ¿qué tenemos? ¿Cuál es la proteína? El frijol, ¿y qué tenemos de carbohidratos? El cereal es este, OK, ¿Qué le hace falta? Aquí hace falta un grupo, ¿cómo le hacemos para poner otro grupo? A pues con lechuga, sale. Y lo hacíamos juntos. Y entonces, cuando llegaban a comer, ya no había una resistencia, ya había que lo que vimos en el aula se trasladó a la comida, ¿no? A la cocina.

Jorge (English Dubbing): Boys and girls and their mothers who cook need to come together with the same information so that we all know what we are going to eat and why we are going to eat it. And when we were making the menus, the kids would say, “Can we have enfrijoladas?” And so we add enfrijoladas. We start by asking, what do we have? Which is the protein? Beans. And what do we have for carbohydrates? The cereal is this, but what is it missing? Here we need a group, how do we make it so we can have another group? Well, with lettuce, it works. And we did it together. And then when they came to eat, there was no more resistance. What we saw in the classroom was transferred to the food, right? To the kitchen.

Eshe: So then I guess my question for you is: What other questions do you have now, after your work with Mano Vuelta, these interactions that you had with the students, with their parents, with Jorge, what else do you want to know about nutrition and learning based on your experience in El Zapotal?

Anahí: These rural communities are experiencing the arrival of a lot of foods that weren’t part of the diet before, especially processed foods. You could see how strong it is, especially for the children: the need to consume these kinds of products that are not good for anyone. This is the bad part of globalization, and you feel like there is nothing you can do to stop it. I think that what I felt was this kind of, I don’t know the word to describe it, maybe “impotencia?”

Eshe: Impotencia is like when you can’t do anything about something, right? Like you feel this frustration at not being able to intervene or to change or to stop something from happening.

Anahí: That’s the feeling. You can’t do anything to fight against sugar. That’s my final message. It’s incredible the effect it has on people, especially on kids.

That’s why it was important for me to share this experience that Jorge had with the community because I think that’s the kind of experience that is the hope for trying to stop this process. And I am interested in documenting and sharing more of these experiences.

Eshe: So I’m guessing at this point in time I’m trying to figure out, what for you is the major takeaway from this story?

Anahí: I think what this story tells us is that learning in groups and through experience is the key to transforming societies. I like the way Jorge describes it when I asked him if he thought his initiative could be replicated in other communities.

Jorge: Yo considero que se puede hacer un trabajo similar como este sin duda, siempre y cuando se tenga paciencia y que la suma de las voluntades se haga más fuerte y que la voz se vaya replicando porque los resultados al final no son inmediatos. Es un trabajo que tu bien lo decías, el día de mañana que en algún punto haya un niño y se siente y ya siendo un padre de familia en el Zapotal diga “hoy no necesitamos un refresco para unirnos ni para sentirnos más o menos, ¿no”

Al final del día lo que necesitamos es alimentarnos bien para estar sanos, para poder tener más momentos para compartir.

Jorge (English Dubbing): I believe that similar work can undoubtedly be done, as long as there is patience and the sum of wills becomes stronger and the voice is replicated, because in the end, the results are not immediate. It is a work in which, as you said, tomorrow there may be a child, and he sits down and already a father in El Zapotal, he says: “Today we don’t need a soda to unite us or to feel more or less, right?”

At the end of the day, what we need is to eat well to be healthy, to be able to have more moments to share.

Eshe: Anahí, thank you so much for talking with me about your research.

Anahí: Thank you, Eshe, for having me and for being so kind.

Eshe: Anahí Ruderman is an Argentinean bioanthropologist with a Ph.D. in biological sciences from the Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina. She is currently an associate researcher at the Instituto Patagónico de Ciencias Sociales y Humanas of the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas of Argentina.

SAPIENS is hosted by me, Eshe Lewis. The show is a Written In Air production. Dennis Funk is our program teacher and editor. Mixing and sound design are provided by Dennis Funk and Rebecca Nolan. Christine Weeber is our copy editor. Our executive producers are Dennis Funk and Chip Colwell. Special thanks to Andrei Boris Seba and María José Burman.

This episode is part of the SAPIENS Public Scholars Training Fellowship program, which provides in-depth training for anthropologists in the craft of science communication and public scholarship, and is funded by the John Templeton Foundation.