Connections and Conflicts With Seals in a Scottish Archipelago

SEAL SONG

One gray afternoon, I saw a seal lying on a rock, eyes half-closed, head tilted toward the wind. It made a low, melodic sound—somewhere between a sigh and a song.

Was it calling out? Mourning? Remembering?

Every now and then, I spot the mammals bobbing in the surf or lounging along the shores of Orkney, a Scottish archipelago, north of the mainland. Their presence feels both ordinary and otherworldly, part of an entangled life where humans and seals have long shaped each other’s survival.

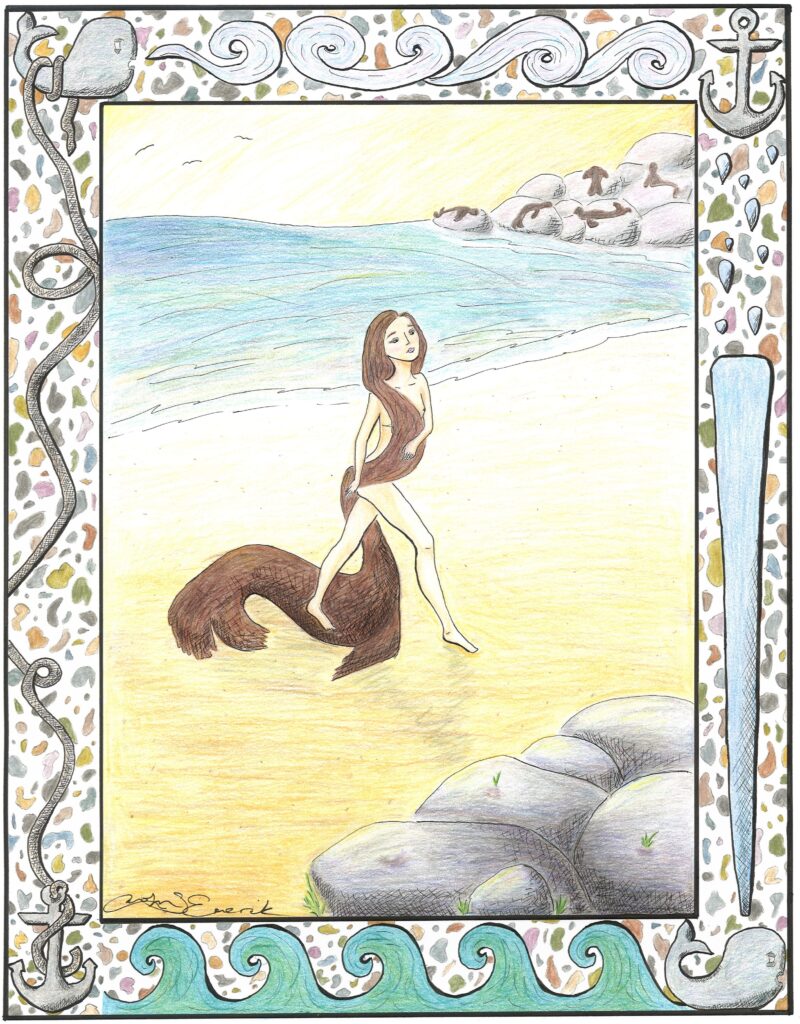

Local shops sell trinkets, storybooks, and postcards depicting selkies, a mythological creature that shapeshifts between seal and human form.

I came to Orkney in 2023 as an environmental anthropologist to understand how mythology and everyday ties between people and seals might guide conservation efforts. I soon realized this relationship was layered, contested, and emotional. Seals have been killed accidentally by fishing gear and intentionally by fishers, who are fearful the marine mammals will eat their fish. Caught between conservation ethos, fishing livelihoods, tourism, and myth, seal protection is fraught.

ORKNEY COMPANIONS IN THE SEA

I left the hot plains of Ahmedabad, India, where I had been completing my doctorate, for the blustery summer of Scotland’s Northern Isles. On a research fellowship, I came to trace how stories about seals—from archaeological remains to folklore to present-day encounters—shape decisions about how to live with them. Among all of Orkney’s species, seals have become the focus of both conflict and care.

During my fieldwork, stories surfaced of quiet but persistent connections between humans and seals.

One islander, who began swimming regularly in the North Sea during COVID-19 lockdowns, found seals often beside her. Once, a seal’s whiskers brushed her skin. From that moment, she began to see herself as part-selkie. When I interviewed her in 2023, she showed me her seal tattoo and said she collects selkie-themed objects and volunteers with the local marine rescue team—cradling pups during birthing season, untangling nets, and sitting with the injured, now a regular experience which she describes as “holding a heartbeat of the sea.”

Another islander recalled walking her dog along the beach when she discovered a pup caught in fishing debris. She freed it with help from a rescue team, and afterward the marked seal often appeared at her whistles, swimming alongside her and the dog.

“He comes close, stays for a bit, and slips back into the water,” she said. “I have two pets now—one in the sea and one on land.”

Others spoke of seals watching them from a distance, eye contact held a few seconds too long, quiet recognition.

“They look at you like they understand,” one older resident told me. “They’ve become companions to my loneliness.”

TIME DIVE WITH SEALS

After weeks of shoreline walks and conversations with islanders, I began meeting zooarchaeologists and animal remains specialists at the University of the Highlands and Islands who have spent decades sifting bones from Orkney’s middens.

When they study material from Neolithic Orkney, about 5,000 years ago, seal remains are rare. At the Knap of Howar, one of the oldest stone dwellings in Northern Europe, fragments suggest occasional hunting, probably opportunistic, for meat or hides.

Moving into the Bronze and Iron ages, seal bones appear more frequently, such as at the Howe site, though not in overwhelming numbers. At a more than 2,000-year-old site, The Cairns, I had the opportunity to join the excavation, and zooarchaeologists trained me to identify seal bones. The finds there included a mix of adult, juvenile, and pup remains, especially from shoulders and forelimbs—the richest, fattiest cuts, what we might think of today as seal steaks.

This evidence points to a probable hunting strategy that targeted every age group of seals across different seasons. Because seal meat spoils quickly due to its high fat content, it was almost certainly eaten fresh and shared communally. At the same site, researchers also uncovered a highly polished seal tooth, likely worn as jewelry, suggesting that seals carried value beyond sustenance.

By the Pictish and Norse periods, roughly 1,700 to 800 years ago, seal use had become more regular and organized. Excavations at Tuquoy show that butchery took place in outbuildings such as smithies, while finds from Birsay Bay include bones with clean chop marks showing evidence of processing meat, blubber, and hide. Norse law codes even began regulating seal and whale hunting. Around this same time, selkie myths first appeared in the medieval texts.

Since the 1700s, the start of the “modern era,” Orkney was exporting sealskins as part of an expanding trade network. Soon, “sealing” expeditions grew large-scale, with hunters sometimes slaughtering hundreds of seals as part of imperial explorations. Expeditions, such as the Hudson’s Bay Company, ventured into the Arctic, where its crews exchanged knowledge and traded for seal items with Inuit communities. Today Orkney museums display some of these items, including ivory seals used as hunting charms and knee-high sealskin boots.

This historical and archaeological evidence illuminated for me seals’ quiet but lasting presence in the islands. But my interest—stories of relation—could not be gleaned from these deep-time data alone. I also needed myth.

SELKIE LORE

During selkie storytelling sessions I attended, each tale carried its own version, yet the core myth was familiar to children and elders alike. Islanders spoke of two kinds of seals, and this distinction matches the actual ecology of Orkney. The smaller harbor seal (Phoca vitulina) is seen as an ordinary animal, while the larger gray seal (Halichoerus grypus) is remembered as the “selkie folk.” Both species can live more than 30 years, with females often outliving males.

Storytellers and elders debated the settings of selkie sightings—on a spring tide, during a midsummer night, or in a hidden cove. Again, story details echo ecology: Harbor seals haul out in predictable, tide-linked patterns, while gray seals return to the same sites year after year.

The origins of selkies were equally varied. Some believed them as fallen angels punished for minor sins. Others said they were humans cursed to live at sea but allowed brief returns to land.

Selkies were said to shed their skins to take human form but kept the skins close and slipped them back on at any sign of danger. Male selkies were notorious for their charm and illicit affairs with human women. The females captivated men. Their skin, often shed on rocks, is considered a symbol of otherworldly beauty and feminine power by literary scholars.

In an interview, Orcadian storyteller Tom Muir explained how these tales adapt:

“When I started telling stories, few seemed interested. Versions vary across places, and thus authenticity is tricky. But every telling adds a personal touch. Folktales passed down orally shape a community’s identity. And yes, they shift with the audience—dialect, names, and meaning evolve, needing careful explanation.”

I was struck by how selkie stories often centered female autonomy. Female selkies choose their partners, return to the sea leaving families behind, and resist the constraints of human society. By giving voice to women’s agency, these narratives shape reality, empowering human women in Orkney society.

Some local anecdotes suggest the figure of the selkie woman may reflect ancestral memories of encounters between Orcadian men and Indigenous Arctic women, who may have been Cree, Inuit, or Sámi. On sea voyages in sealskin-covered boats, or umiaks, these Arctic people wore sealskin clothing and carried items carved from seal bone. Such encounters may have helped inspire the selkie myths.

These layered histories of how seals were used, imagined, and storied in Orkney continue to shape arguments over how they are treated today.

IS THE FUTURE OF SEALS SEALED?

Orkney has stepped up seal conservation in recent decades, but divisions among islanders remain sharp. Seals face pressures from declining fish stocks, accidental entanglement, and conflicts with salmon farms, where they are sometimes killed under licensed “lethal control.” That tension boiled over in October 2022 when a seal who entered a fish farm was fatally shot, triggering outrage among conservationists and renewed debates about how human-seal conflict ought to be handled.

Who should decide how seals are managed: local fishers, storytellers, national agencies, or international conservation groups? The killing highlighted a long-standing dilemma over whether seals are competitors or kin.

For fishers and businessowners, seals remain a double-edged presence: culturally significant yet a threat to livelihood, blamed for damaged nets and lost catch. As one fisherman told me bluntly, “We don’t want the seal, they’re just creating ruckus, they always have. We don’t mind shooting one or two down.”

Tim Dean, an educator at the Orkney Council’s Community Learning and Development service, rooted this animosity in economics: Seals are often framed through money, either as income from visitors or as losses to the fishing economy. Folklore deepens this divide, casting seals alternately as benign shapeshifters or malevolent tricksters.

The rise of Scotland’s salmon farming industry in the 1960s and ’70s intensified tensions between fishers and seals. Hostility peaked: Many fishermen were licensed to shoot seals and viewed culling as a necessary evil. Farmers have often accused harbor seals of eating their stock, though diet studies show the seals feed largely on smaller fish like sand eels, with salmon predation occurring mainly in specific estuaries and seasons. High-pitched acoustic devices have been deployed in a study to scare away seals, but their sounds also disoriented porpoises and dolphins.

As the fish farm industry grew influential, grassroots conservation efforts also began to take hold. Ross Flett, known locally as the “seal man,” co-founded the Orkney Seal Rescue in 1988, which grew out of protests against culling to become a volunteer-run refuge for stranded pups and injured adults. He and his partner still run it largely on donations and community alerts. They believe stricter laws and better citizen science can tip the balance toward protection.

I cannot divine the future for Orkney’s seals, living symbols that remain precarious yet protected, ancient yet evolving. But I am confident the islands’ people and seals will continue their entangled bond of resourcefulness and kinship, conflict and care, survival and long memory.