Salt and Paper in Bureaucratic Jerusalem

Documents used as proof of residency by the Israeli authorities may include:

-A rental contract

-Electricity bills

-The GPS log of a smartphone

-Grocery receipts

-School homework

Objects that may cause bureaucratic problems for the Palestinians of Jerusalem:

-A warm car engine

-Expired deli meat

-Clean laundry

-Wilting plants

-A misplaced saltshaker

A typical scene goes something like this: A Palestinian family registered as living in the city of Jerusalem is in the process of renewing their residency status. At their last appointment, the Israeli Ministry of Interior staff told them that inspectors would visit them at home. They received phone calls from the ministry checking on them: micro interrogations. One day, a pair of inspectors arrives at their door. On this occasion, one of the first questions they ask is: “Where do you keep the salt and spices?”

The stakes of answering such mundane questions correctly couldn’t be higher. Unlike Israeli citizens, if Palestinians from Jerusalem (Jerusalemites) fail to provide sufficient evidence that they live in the city, authorities may revoke their residency status—threatening their access to Jerusalem and their homeland, Palestine, altogether.

“The story of the spices and the salt, that one stayed with me,” the Palestinian visual artist Yazan Khalili told me during a recent interview. In March 2025, I called Khalili for a conversation about his 2018 project exploring how Israeli bureaucracy affects Palestinian Jerusalemites’ everyday behaviors and senses of belonging.

“You don’t have a chance,” Khalili said. If you can’t tell authorities where the seasoning is, he explained, “it will be recorded as a point against you, that you don’t actually live in that house.”

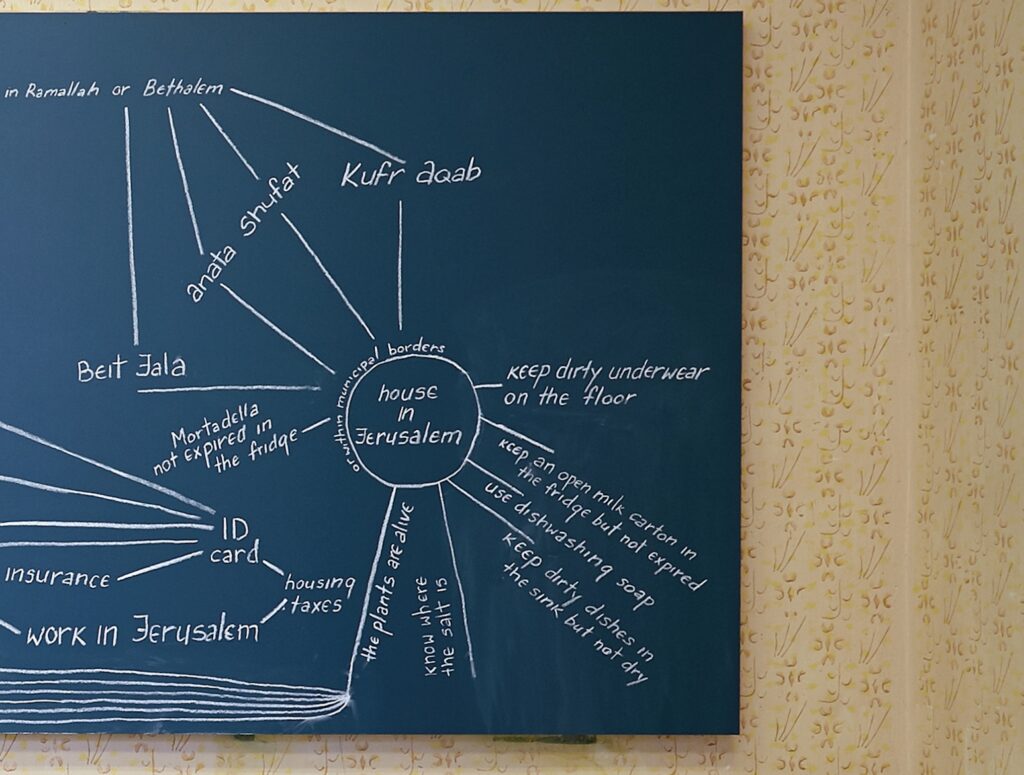

To avoid displacement once a household is bureaucratically marked by Israeli officials, Palestinian Jerusalemites must collect reams of documentation proving their residency there and carefully curate their homes. A single item out of place or a missing document can damage their case. For many Palestinians, this “center of life” policy, in the legalese of the Israeli state, makes everyday life into a dangerous and exhausting exercise in proving oneself present.

State violence operates at the smallest of scales and spaces of everyday life.

As a political anthropologist who studies colonialism from the vantage of Palestine, my research investigates the bureaucratic processes by which Palestinians in Jerusalem must prove they belong to the Israeli state that categorically denies them as subjects.

In the modern history of Palestine, Israeli Zionist settler-colonial violence aimed at the systemic displacement of Palestinians has manifested in different forms, intensities, and scales. The Israeli genocide against Palestinians in the Gaza Strip, carried out with impunity and with the direct support of the U.S. since October 2023, reveals the spectacle and terrifying violence of state power. In 20 months with near-daily massacres, Israel has dropped more explosives than were used during World War II onto over 2 million people living in a territory just twice the size of Washington, D.C. Israel controls all movement, food, and supplies in and out of Gaza.

I was interested in talking to Khalili because, like my own research, his work explores how Israeli rule also operates on a smaller, quieter scale. In subjecting families to exhaustive bureaucratic processes, the Israeli state consistently contains and reduces Palestinian life—infiltrating even the most intimate spaces, like the spice cabinet where the saltshaker has gone missing.

To learn more about the author’s work, listen on the SAPIENS podcast: “Protest and the Public University.”

CITY OF PAPER

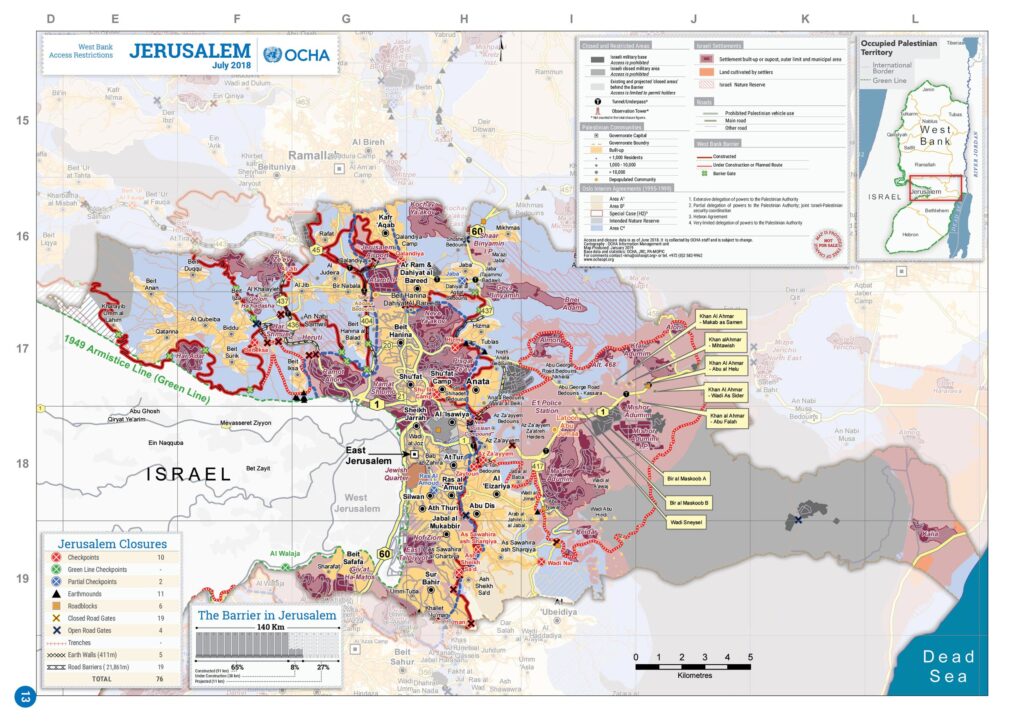

Some 400,000 Palestinians live in Jerusalem, making up around 40 percent of its population of about 1,000,000 (if you count the Jewish-only settlements encircling the city, as Israel does). Palestinian Jerusalemites are born in the city and trace their lineages many generations back. However, despite being Indigenous to Palestine and the city, Palestinian Jerusalemites are not citizens. In 1948, Israel occupied the western half of the city, and, in 1967, the government began exerting power over the eastern half, along with the Palestinians who lived there and who were not displaced outside of it. Israel unilaterally declared sovereignty over East Jerusalem and formalized it through annexation in 1980.

Under these conditions, the generations of Palestinian Jerusalemites born in the settler-colonial capital city since 1980 have been forced into a temporary state with tenuous access to the city and their homeland. Legally speaking, they were granted the status of permanent residency rather than citizenship. Technically, Palestinian Jerusalemites may apply for Israeli citizenship, although the Israeli government awards it on a case-by-case basis. A small number of Jerusalemites have obtained (limited) citizenship this way. However, the Israeli government’s overall strategy has been to continually reduce the proportion of Palestinians in the city.

One tactic they employ is revoking people’s residency status. In a landmark legal case in 1988, Israeli legislators used the concept of “center of life” to justify the deportation of the Palestinian academic and peace activist Mubarak Awad. Starting in 1995, Israel formalized this policy and began implementing new regulations and administrative tactics to revoke residencies of Palestinians in Jerusalem en masse. This “quiet deportation” policy has resulted in over 14,000 displaced from the city and Palestine in general.

When Palestinians have their residencies revoked, they’re also removed from the Israeli-held population registry, thereby preventing their ability to return to Jerusalem and live there in the future. This status quo continues to define the Palestinian experience and ensures a Jewish-Israeli majority in what Israel claims as its capital.

Palestinians in Jerusalem often refer to the government that rules over them not as the “Israeli State” but as the “Paper State.” Potential triggers of the bureaucratic apparatus can include anything from leaving the country, replacing a worn-out ID card, missing an electricity bill of your apartment from June 2003, renting or owning more than one residence, marrying a Palestinian (especially from the West Bank or the Gaza Strip), registering the birth of a child, or using (or not using) the public health system.

To attempt to avoid displacement, many Palestinians in the city produce paper trails of their everyday lives as they conduct them in Jerusalem. During my fieldwork, people told me they maintain files of rental contracts and utility bills, a GPS log to confirm where they sleep at night, and even ephemera like grocery receipts and school projects. On multiple visits with families in Jerusalem, parents told me about how inspectors checked the date of their children’s homework. The implication was that if the date was not current enough, it could count against them. Schoolwork has even made it into Israeli Supreme Court cases about Palestinians’ residency status in Jerusalem.

On a large scale, Palestinians in Jerusalem carefully manage their homes and patterns of living to prevent their intimate spaces and household objects from becoming potential evidence against them in the eyes of the bureaucracy. For instance, Khalili told me about one of his friends who was fretting over the state of her houseplants. He asked why she didn’t just get rid of the plants, considering how much anxiety they caused her since if they were to die a potential inspector could read them as evidence of her false presence. She responded that having no plants at all would look even more suspicious.

ART BY PROXY

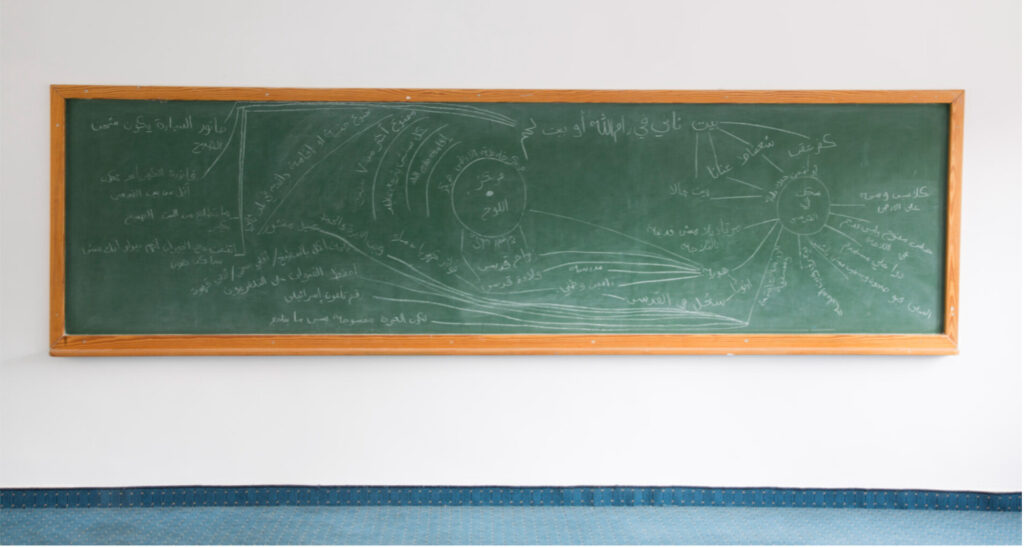

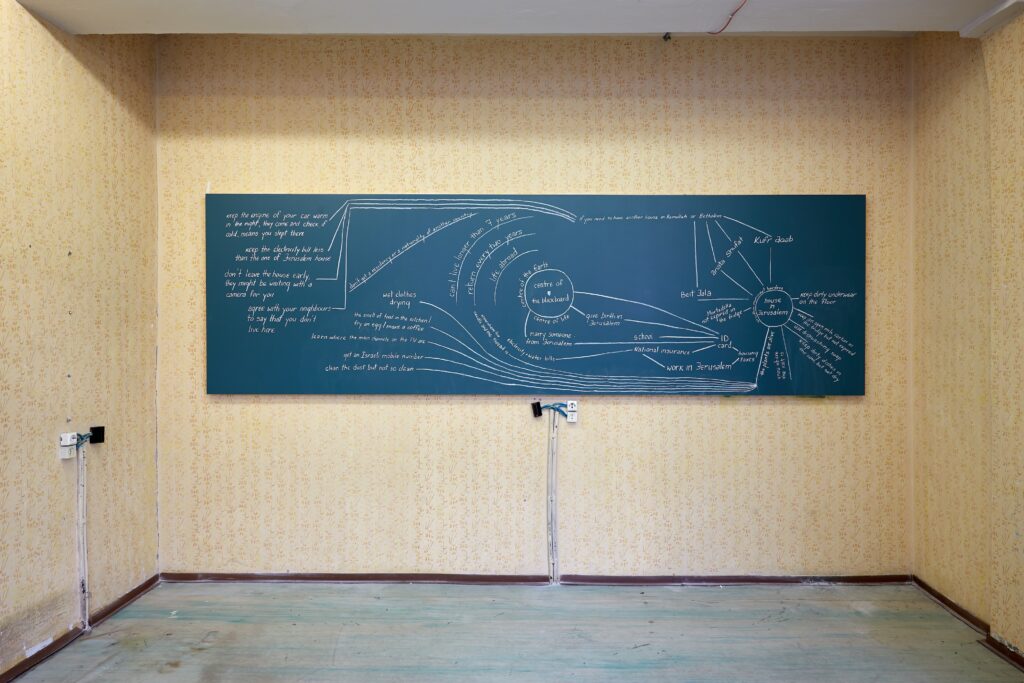

Khalili’s 2018 work “Centre of Life” is a chalk diagram that visualizes and describes the devilish details involved in making a life in Palestinian Jerusalem. As he explained in a curatorial statement, “It explores Jerusalem not as a place but as legal processes and paperwork. I ask how the city is maneuvered through legal procedures and the life decisions one must make to insure [ensure] access and ability to live in the city.” The work demonstrates the web of social relations caught in bureaucracy and living in Jerusalem in “a time of apartheid and destruction.”

The work has been staged twice—once in Jerusalem and once in Latvia. But Khalili has never seen it in person. In 2018, when the piece was first shown in Jerusalem as part of an exhibit, he lived in the West Bank city of Ramallah, about 12 miles away. Holding a West Bank residency status that is distinct from Jerusalem residency status, he is not allowed across the militarized checkpoint system separating Palestinians in the West Bank from those in Jerusalem and the rest of Palestine.

In his stead, Jerusalem artist Essa Grayeb drew the diagram in Arabic on the chalkboard based on designs Khalili provided. The drawing lists aspects of living at the precipice between maintaining a “center of life” and displacement: ID cards, restrictions on where and how one can live, the objects of the home, the problems with having multiple residences, health insurance. Since Khalili cannot access Jerusalem, the details presented in his diagram were based on stories from his relatives, friends, and encounters with other Jerusalemites. His work was an aggregate retelling of the behaviors and patterns one has to learn to cultivate for Palestinian life to be viable in Jerusalem.

Khalili explained to me that the first showing of this work received lots of feedback from the audience. Palestinians in the city who came to see the work expressed recognition and, crucially, shared parallel experiences with him. Khalili later incorporated some of these suggestions directly into the work itself. For example, he edited the diagram to include a question an audience member received from an inspector who asked which TV channel the news was on.

However, when the work was shown in Latvia in 2020, it met a different audience reaction. There was no budget for Khalili to attend the event in person, but he learned later from those present that foreign audiences had reacted to the violent absurdities of Israeli Zionist rule with disbelief.

“When you speak about Palestine, people really react to you as if you are insane,” Khalili told me during our interview. “Zionist violence on the imagination is so intense that the attempt to explain it makes you crazy,” he added.

MINUTIAE AND ELIMINATION

Khalili’s work apprehends and communicates how state violence of elimination operates at the smallest of scales and spaces of everyday life. These insights align with those of anthropologists, especially feminist anthropologists who have long argued that structural and intimate violence are intertwined and inhabited in the space of the home.

In Jerusalem, minor details about how one lives, such as knowing the location of the saltshaker, are ultimately tied to whether people can maintain access to their homeland or whether they will be displaced. I think of this as the minor key of dispossession, which contrasts but also works in collaboration with the major key of dispossession—including segregation walls, land appropriation, home demolitions, mass incarceration, political assassinations, engineered famine, and genocide.

Given the scale, intensity, and mass consumption of this unfettered state violence, the minutiae of daily life are easily overlooked. But the ways in which people in Jerusalem relate to their homes and its objects is a necessary perspective for anyone witness to and undone by the Israeli genocide. Paying close attention to the minutiae helps reveal the underbelly of the politics of elimination and how those politics shape all aspects of living. These small facets, from schoolwork to potted plants, reveal how Palestinians’ existence in Jerusalem under Israeli rule is fundamentally contingent on proving that they do, in fact, live.