How Bird’s Nests Become Markers of Vitality and Status

I’m in one of Bangkok’s ubiquitous convenience stores when I spot a section of little bottles labeled “bird’s nest beverages.” These drinks include a tiny amount of edible fragments of nests made by swiftlets (most commonly Aerodramus fuciphagus), small gray birds that build delicate, cup-shaped, translucent nests with their own saliva, unlike most other birds that use twigs, mud, and other foraged materials.

When simmered in water, these nests create a mild-tasting, jelly-like broth long prized in East and Southeast Asia as a delicacy with purported nutritional and medicinal properties. The ready-to-drink bottles containing a small amount of this prized ingredient come wrapped in gold and red boxes—and with a “golden” price tag of up to 129 baht (around US$4), much higher than most of the other items on the refrigerated shelves.

When I ask the convenience store employee what the beverage is for, she replies, “It’s for good health and stamina.” When I probe a bit further, she tells me it’s popular among “local men, and tourists who want to try [it].” When I tried the tonics, I found that their mildly sweet syrup with jelly-like threads made it quite similar to other regional desserts, save for the “1.1 percent bird’s nest” that’s supposed to make the difference.

Seeing the beverage in Bangkok, I’m reminded of my home country, the Philippines, where swiftlets nest in the cavernous rock formations in the mountains. Being on those mountains, with their jagged limestone edges surrounded by turquoise waters, one feels worlds apart from the air-conditioned convenience stores and sprawling malls of Bangkok. Yet these places are intimately linked: by the swiftlets, their nests, and the human practices that have shaped them.

As a medical anthropologist, I’m fascinated by the political, economic, and social networks that have transformed humble bird’s nests into one of the most expensive animal products in the world. These connections reveal the great lengths some people will go to produce and consume in-demand products, regardless of the risks or impacts on other humans or birds. What notions of health, vitality, and value are at work when bird saliva becomes a luxury tonic? And how do these meanings travel across borders, shaping the birds’ own journeys?

Swiflets’ nests (yan‑wo; 燕窩) have been a highly prized delicacy and prestige food in China and other parts of Asia since ancient times. In traditional Chinese medicine, the nests, usually served boiled in a soup, are thought to act on the pulmonary, gastrointestinal, and renal meridians; the late 16th-century Ben Cao Gang Mu (Compendium of Materia Medica) describes the food as good for the lungs and for treating respiratory ailments.

The actual nests come from Southeast Asia, and unsurprisingly, the history of the nest trade with China is just as old—reaching back to the Tang (A.D. 618–907) and Song (A.D. 960–1279 ) dynasty periods. Archaeological excavations at Niah Caves in Sarawak, Malaysia, have found nest‑scraping iron tools in the same layers that also yielded Tang‑ and Song‑style ceramics, indicating bird’s nest harvest and trade activities.

Some accounts credit the Ming dynasty voyages of the admiral Zheng He (1371–1433) for bolstering this trade in later centuries. These “treasure voyages” (1405–1433), which reached as far as East Africa, integrated local polities into a wider tributary-trade system of exchanging exotic commodities for economic gain and political recognition. Bird’s nests may have become one of the tribute items offered between rulers in Asia as part of these developing trade networks.

As time went on, the nest trade became highly lucrative, with their value rivaling that of other prestigious goods like spices, sandalwood, and ivory. Chinese merchants established long-standing relationships with local rulers and Indigenous harvesters in Southeast Asia, sometimes marrying into local communities or gaining monopolies through tribute arrangements. According to anthropologist Mohamed Yusoff Ismail, the Idahan people of Sabah, Malaysia, recount that their ancestors involved in the trade during this period “were quite cautious about disclosing the exact locations of the nesting caves, but assured [the Chinese] of a continuous supply if [they] agreed to wait at the coast.”

Writ large, such relationships comprised dense, overlapping networks of commerce, kinship, and ecology that predated European colonialism and persisted alongside it once the Spanish and Dutch entered the region.

Fast forward a few hundred years, and the global bird’s nest trade is still booming—but in new forms.

In Palawan, an island in the Western Philippines routinely ranked one of the world’s best tourist spots, hiking guides often double as busyador, or nest harvesters. Busyadors embody centuries-old practices while participating in the enduring historical networks forged by humans and swiftlets alike. When I lived there from 2014 to 2016 conducting anthropological fieldwork, harvesters told me how lucrative it was to collect the nests, with 1 kilogram—a hundred or so nests—fetching thousands of dollars.

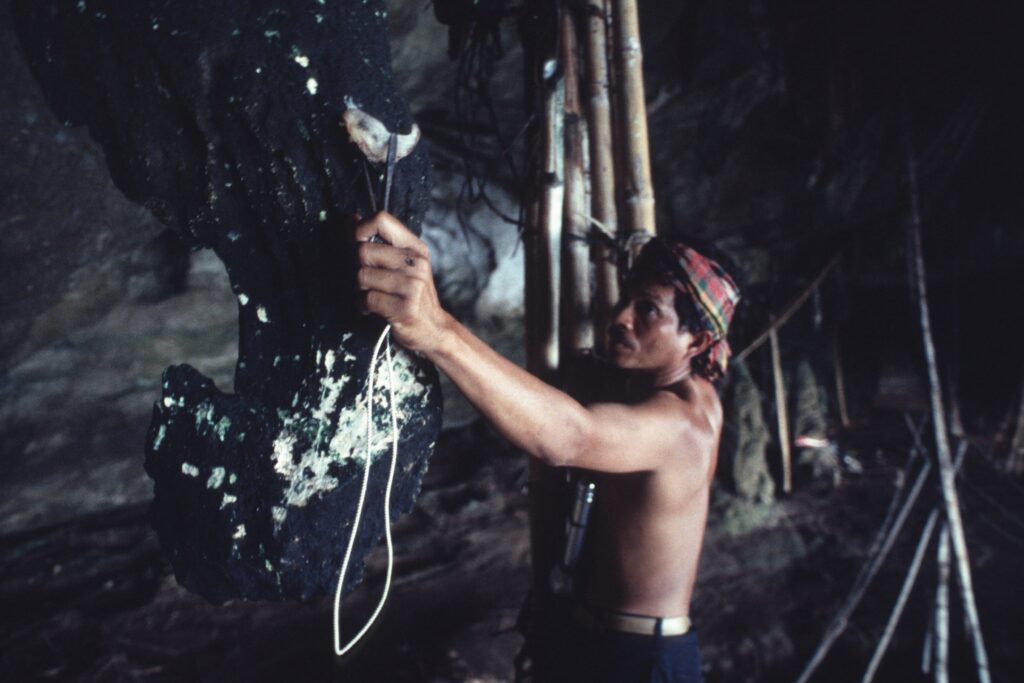

But obtaining the nests is difficult and precarious. Busyadors, after acquiring the requisite skills of rock climbing and harvesting with specialized tools, risk injury and even death. Beyond the skills, a certain sensibility is required; geographer Paula Satizábal and colleagues note that “the art of harvesting nests requires conquering the fear of darkness, tight places, and heights”—all while navigating uneven geological landscapes.

Generations of harvesting bird’s nests have given rise to rituals like burning incense and praying to the caves’ ancestral spirits for protection. Communities where the practice is common have also developed customary laws governing access to certain caves. However, the increased value of the nests has given rise to new regulatory practices and intense competition in some regions. Anthropologist Kasem Jandam, who has surveyed bird’s nest practices across Southeast Asia, has found that traditional harvesters are invariably on the losing end of a changing economic landscape increasingly driven by wealthy outside investors.

In recent decades, there’s another source of competition for traditional harvesters: humanmade swiftlet houses, a.k.a. “bird’s nest condos.” The history of bird’s nest farming is hazy, likely dating back over a century. More recently, entrepreneurs in Thailand, Malaysia, Vietnam, and elsewhere in the region have scaled up these efforts by converting old structures or building new ones designed to mimic the swiftlets’ natural dwelling places. They keep the dark, humid sites clean and equipped with ventilation, water, and other amenities to ensure the best conditions for production.

The proliferation of such buildings and the precarity of the wild swiftlet population have led to even stiffer competition, leading many in the industry to install speakers to blare out bird calls to attract the swiftlets. According to The New York Times, condo owners in Indonesian Borneo now “compete to lure the swiftlets by playing recordings of the clicking sounds they make as they echolocate.”

Some people have raised concerns about the condos, including complaints about the noise and other risks and discomforts they pose to urban dwellers. Others tout them as a more sustainable alternative to traditional harvesting, which carries its own ecological impacts, including overharvesting that can disrupt the birds’ reproductive cycles.

Despite these challenges—and some critics who see the entire practice as cruel—the demand for bird’s nest products continues to expand and reach new markets.

The edible bird’s nest market is now a US$8.45 billion industry, driven by overlapping desires for beauty, health, and status.

While consumers in Asia still make up 90 percent of the market share, exports to North America and Europe are growing, in part due to an increase in Asian immigrants in these regions. In addition to luxury soups and other high-end dishes consumed primarily by wealthy, urban Chinese, bird’s nests now feature in a wide range of ready-to-drink tonics, jelly desserts, capsule supplements, and beauty and skincare products at various price points to appeal to a broader consumer base.

These products claim to have an astounding array of health benefits, including boosting immunity, enhancing skin, improving respiratory function, and even promoting fertility and longevity. Such claims have since been the subject of a “great amount of research,” but evidence of their benefits remains limited and inconclusive. Yet their appeal persists, animated by a convergence of cultural beliefs, contemporary ideals, and marketing that frames the nests as both traditional and modern, natural and scientific.

Back in Bangkok, locals I spoke to about the convenience store version of edible bird’s nests were often skeptical about the drink’s therapeutic claims. But some were willing to give the tonics a shot anyway. “Sometimes I try it, and I think it has an effect,” one told me.

Some nest harvesters, for their part, subscribe to the health benefits of what they’re collecting. On a recent hike in the Sierra Madre mountains of Rizal province in the Philippines, my guide told me consuming the nests provides energy. “You won’t get tired for the whole day,” he said, as swiftlets flew around us. But when I asked if he ever keeps the nests to consume instead of selling them, he told me, “I’d rather take the money.”

When I look at swiftlets flying above, I marvel at how their unlikely migrations across the region entangle with human livelihoods, dreams, and desires. The birds and their nests have “social lives” that reveal how shifting sociocultural ideas and political and economic pressures shape what gets to be considered medicine.

Yet it’s sobering to consider that while some consumers can afford to pay a high price for the tiniest amount of bird’s nests in restaurants and convenience stores, the real cost may be one of increasing precarity and marginality for ecosystems and human communities alike.