The Tangled Roots of Corruption in Today’s South Africa

I am sitting in the back of a Department of Corrections Toyota Hilux, my bum numb after cruising the potholed streets of Bonteheuwel, one of Cape Town’s surrounding townships with a reputation for high crime rates and gang conflict.

From the front seat, department member Mbiko hands me a bag of McDonalds with a quarter pounder and fries. [1] [1] All names in this piece are pseudonyms to protect people’s identities. Mbiko is an employee of Community Corrections, or CommCorr, the branch of the Department of Corrections that supervises parole, community service, and probation.

It is dark and cold outside, and the warm food is welcome after a day following her in and out of people’s homes, observing her enforce parole conditions.

“Cooldrink money,” says a winking Mbiko, affectionately referred to as “Bibi” in the Cape Town CommCorr office. She is referring to the crumpled, pink R50 notes she used to pay for the meal. Earlier in the day, men in the street hailed our bakkie (truck) and handed money through the window.

“You can’t call it a bribe,” she said. “How is it a bribe when people come to the office and ask for me to give them transport money to get home?” To Bibi, this was a quid pro quo. Money went out of her wallet when she was at the CommCorr office and came back in when she drove the streets of Bonteheuwel. It didn’t have to be from the same person.

Had I just witnessed the infamous corruption of government employees in South Africa? Had she accepted a bribe right in front of me, justified it, and bought me dinner with it?

I had spent the last year visiting correctional centers and CommCorr offices in my home country of South Africa as part of research for my doctorate in anthropology, which I began after leaving my first career in law. I was learning that much of what I had been taught about the difference between right and wrong didn’t translate to the world outside the statutes and case law.

Corruption, with a capital C, is a loaded word in South African political discourse. For many South Africans, it conveys deep feelings of betrayal. Since former President Jacob Zuma, who held this position for nine years, was charged with Corruption, money laundering, and fraud, government has become associated with corrupt actors. The Corruption scandals, including ongoing crises over rolling blackouts, shape how many South Africans think about their government. Despite efforts to address this perception by Zuma’s successor, Cyril Ramaphosa (himself associated with perceptions of Corruption), a resounding protest ushered the result of the 2024 national election: For the first time since post-apartheid elections began in 1994, the African National Congress (ANC)—Nelson Mandela’s political party—lost the majority vote.

But what I saw happening between Bibi and the residents of Bonteheuwel looked nothing like the reports of political Corruption that dominate the South African news cycle. What I witnessed looked like survival: groups of people who had been divided by apartheid racial classifications, and later by labels of the criminal justice system as “perpetrator” and “parole officer,” giving and taking to endure in the deeply unequal present.

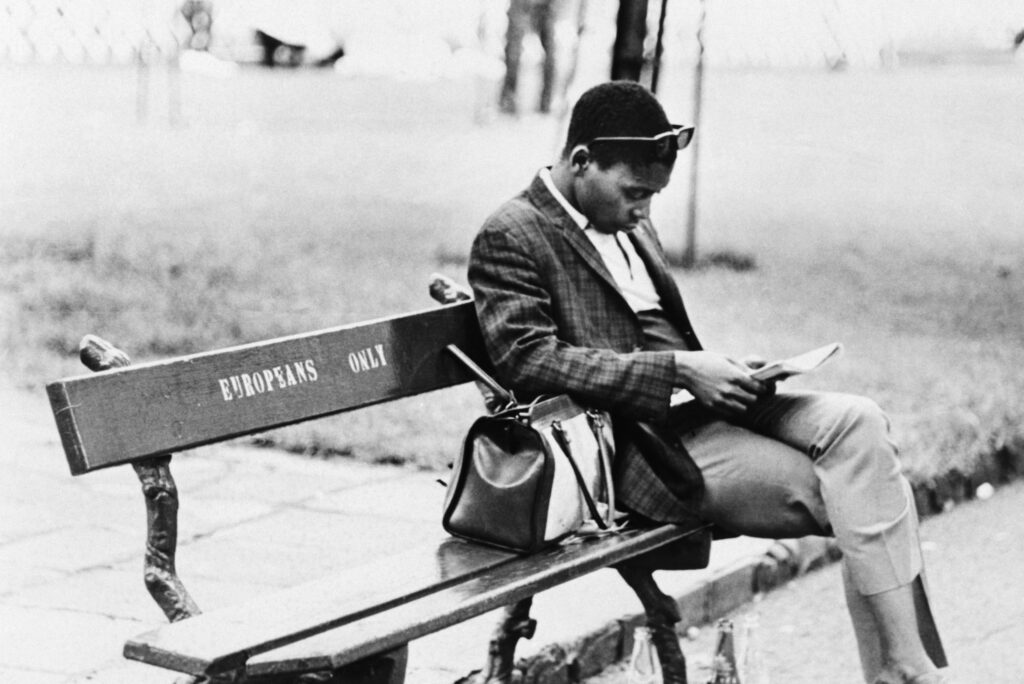

PART OF WHAT MAKES South Africa’s present so complex is how different white governments assigned non-white people to a hierarchy of racial categories. These enforced classifications affected land dispossession and relocation, labor exploitation, extreme racial segregation, political representation, and much more.

For example, in 1950, the apartheid government legally defined Black Africans as “Bantu” or “Native” and further divided them into artificial, state-defined tribal communities. Making up the majority of the population, Black Africans were cast into and placed on the lowest rung of a racial hierarchy based in the tenants of scientific racism. Slightly up from this category were descendants of Khoe, San, and Malay people who were legally defined as “Coloured.” Most in this group speak Afrikaans, and animosity and distrust persist between those who are Coloured and Black Africans. A minority white population (primarily of two ethnic groups: Afrikaans speakers and English speakers) benefited from apartheid and were given the most privileges and opportunities. Later, “Indian” was added to encompass people of South Asian descent.

These arbitrary racial divisions still impact the lives of South Africans. Bibi is amaXhosa and would have been considered Bantu by the apartheid government. The community we drove through in Bonteheuwel is defined as Coloured.

Before beginning a doctorate in anthropology at the University of the Western Cape, I worked as a legal researcher in South Africa. My legal training taught that a line exists between actions that are “good” and ones that are “bad” and deserve punishment. Anyone who committed any act of corruption, large or small, was defined as bad in the law.

What these binary categories obscured became complex and ambiguous when I saw it through the lens of anthropology. I began to wonder how the history of colonial conquest shaped present government Corruption.

In parts of Africa colonized by British forces, primarily in the 1800s and into the 1900s, colonial administrators kept traditional forms of leadership intact so long as those leaders served British interests. When amaXhosa chiefs in what is today the Eastern Cape region resisted British encroachment on their land and capture of their cattle, they were murdered or imprisoned.

One such chief was Jongumsobomvu Maqoma, who led many campaigns and fought against Cape Gov. Harry Smith in the early 1850s. The conflict began when Smith blamed the amaXhosa chiefs for unrest in the area—unrest actually caused by displaced people being forced to live in crowded conditions along the Kei River. Although Maqoma and others led an extended resistance from within the Waterkloof and Amatole mountains, the British simply had more forces. Maqoma wound up imprisoned. When he was released, he found his people dispersed, working on European farms that came to occupy his former homestead.

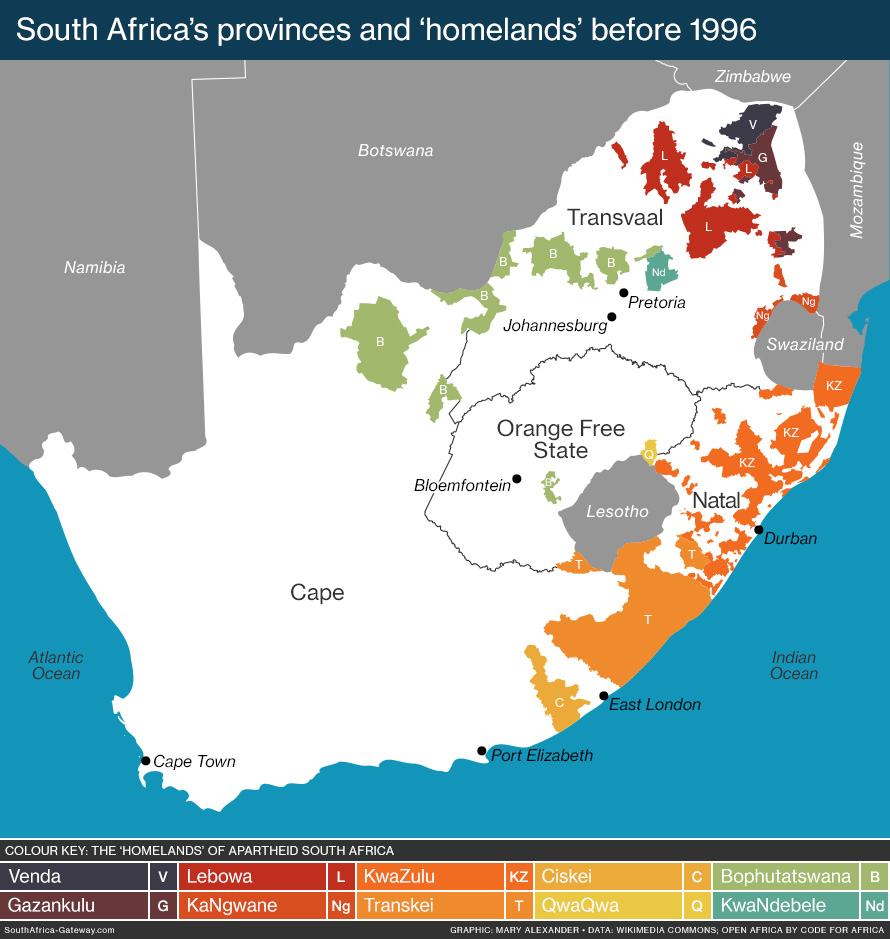

Once all the Cape’s land and people were inside the British colony, the British came to disrupt the former power of the chiefs by installing puppet chiefs who were paid by the state. Where, previously, chiefs had governed only through community consent, those put in power by the British answered to their paycheck and not their people. This system would form the bedrock of the apartheid state’s Department of Bantu Administration and Development, in which the government created 10 “Bantustans” organized by pseudo-ethnic identities—four of which became notionally independent tribal states within South Africa, all of whom had leaders loyal to the white government. These leaders had immense control over vulnerable populations that had been removed from their original lands. Between 1960 and 1982, over 3.5 million people were relocated.

THAT DAY WITH BIBI and Cagwe, the man driving the Hilux, I wanted to learn how they performed a task called “monitoring.” The people they monitored, referred to in department-speak as “clients,” had been released from prison on parole and were under house arrest. Bibi and Cagwe went to each client’s house and confirmed the person was there. If someone was missing, the client could be reprimanded. If someone was missing too many times, they could be sent back to the correctional center.

On our drive around Bonteheuwel, we stopped at a white brick house with bars on the windows. Inside, we met a young man named Mitchell living with his mother. Bibi clearly had a long history with him because his mother called her inside to complain:

“He’s running around at night, off selling drugs and trying to be a gangster like his father.”

The following Monday, Bibi sent Mitchell back to the Pollsmoor Correctional Center. He lost his parole. These were the stakes.

The apartheid government created arbitrary racial divisions that still impact the lives of South Africans.

The men I saw handing money through the bakkie window were out and about instead of at home under house arrest. They needed to stay on Bibi’s good side, or they’d wind up back inside.

The money represented appreciation. From where Bibi sat in the front passenger seat, she was aware that to the researcher in the back, this would look like a bribe from the men not complying with house arrest. But she knew their lives and situations were more complicated than the black and white of their parole conditions.

THE 1994 COALITION GOVERNMENT, called the Government of National Unity (GNU), led by the ANC, inherited a fractured system of chiefs and ward councilors who had through many years of white rule produced governance that was deeply corrupted. In the years since the 1994 election, that stain of inefficiency, bribery, and cash-grabbing has settled over the ANC government.

In South Africa, according to the nonprofit research network Afrobarometer: “Most citizens say ordinary people risk retaliation if they speak out against corruption, and only a few believe that the authorities will take action in response to reported corruption.” Along with unemployment and intermittent electricity, corruption was among the South African population’s top three concerns heading into the 2024 national election. But this concern is not limited to the highest politicians; rather, it extends to how South Africans view the police and civil servants.

Where does this leave Bibi, who bought me dinner with money she received in violation of department policy?

The day I spent with her in Bonteheuwel was her last. One way the department tried to stifle corruption was by moving people around regularly. Not because of her cash exchanges but due to this standard practice, she was transferred to a different function inside of CommCorr. She was more than relieved to leave that community behind and take up a more administrative role. At every stop we made, she told clients and their families that someone new would visit them next week. They worried about who would replace her.

One woman, frying up tomatoes and bacon as she talked to Bibi, said: “You treat the Coloured people with respect. Those others, they don’t do it.”

Tensions between people defined as Coloured and those who are amaXhosa like Bibi is the kind of legacy obviously associated with apartheid.

Less known is apartheid’s role in corrupting systems of government the white minority had been using to their advantage for 40 years. During apartheid, government was a reliable source of employment for white people, and the government provided many social services. When, in the 1980s, the political tide began to favor Black resistance fighters, white government leaders privatized multiple state functions. They gave contracts to white-owned businesses to take over government-run services, gutting government jobs. The system of government was corrupted by white elites as they lost their grip on power.

The grand Corruption we see taking place now, with elites lining their pockets and paying little heed to the people, is a continuation of the puppet chiefs used to govern the amaXhosa and other Black African groups. It is also a continuation of the mass draining of government funds and services into the private sector. Little resources are left for Bibi and her clients to survive—without a little corruption of their own.

When I think back on Bibi’s last day monitoring, one man stands out. He and his wife lived in a lean-to propped against another family’s small brick house. He had been sent to prison for sexual assault of a child. His wife remained with him and supported him now that he was on parole. She respected and appreciated Bibi for how she treated her husband—as a person. He came to the CommCorr office a few days later (a requirement of his parole) and took the opportunity to drop off a lemon meringue pie his wife had baked for Bibi.

“Smokkel,” she said, before offering me a slice. [2] [2] Smokkel means “smuggle” in Afrikaans and is a slang term used in this context to refer to illicit goods like drugs, guns, and cellphones brought into the correctional center. She liked to tease me about all these supposed violations of department policy I was witnessing.