Witnessing an Endangered Puberty Ritual

It was before dawn. I lay curled up in my thin sleeping bag on the wooden floor of a jungle hut in south-central Peru, while an Indigenous elder performed his ritual morning song. The morning sounds of the village were punctuated by someone gleefully crying, “Ahueney ponapnoro!” In the Yanesha’ language, that meant “let’s all go to ponapnora”—a celebration marking the passage to womanhood.

When menstruating for the first time, a young Yanesha’ girl is traditionally sheltered in a leaf-walled hut for one to six lunar cycles. In the traditional custom, she would undergo a lengthy purification that includes a strict diet of water, herbal teas, and cold, unsalted manioc root. Through visits from her female relatives, the girl would learn traditional life skills, such as weaving cotton thread into textiles and brewing plant medicine. If she was part of a song-keeping lineage, she would be taught to sing traditional Yanesha’ women’s songs. At dawn, after a full moon, the community would come together to feast and celebrate the girl’s emergence as a strong, healthy, and capable woman, ready to start her own family.

Like many other long-running rituals in South America, ponapnora is at risk of disappearing among the Yanesha’ because their lives are rapidly changing. Many members are migrating to cities, and extractive resource industries are making inroads into their territories. Cultural assimilation, a shift toward Christianity and its rituals, and an adoption of the Spanish language are among the many factors leading to the erosion of traditional Indigenous customs.

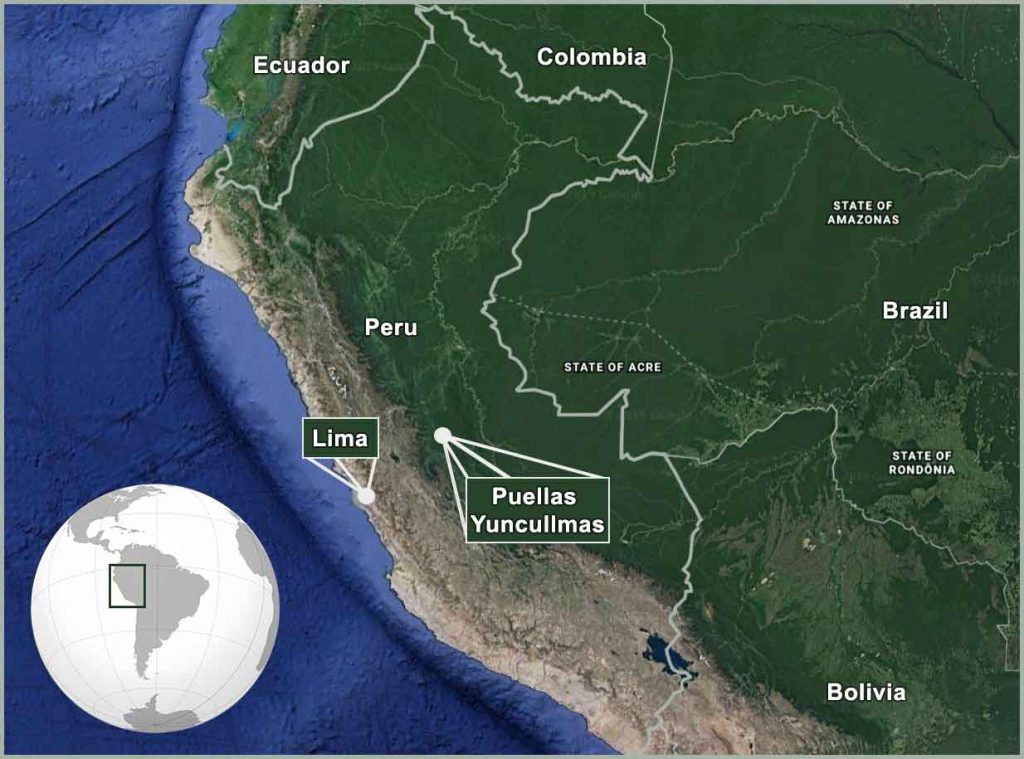

When I visited the remote Yanesha’ community of Puellas Yuncullmas, the ponapnora ritual remained alive among the 100 or so inhabitants of the settlement. It was still seen by many as vital to a woman’s long-term health and was considered a cornerstone of social life. It is likely still integral, though some things are changing. The need to learn how to weave textiles is ebbing, for example, as factory-made clothes make their way into these communities. The ritual is becoming shorter and less commonly practiced. Traditional songs are not passed down as often as they once were. But at its core, the ritual, a one-time event that marks the transition into womanhood, remains the same.

I had the opportunity to witness a ponapnora ceremony a decade ago when I was a graduate student working in Yanesha’ territory on a large project to create an oral history archive for the Yanesha’ people (now available online in Spanish and Yanesha’). As an anthropologist, I wanted to document the puberty ritual—not just to explore the community’s culture but also to help, in a small way, preserve it for future descendants. Should this custom eventually fade, members may wish to research and revive it as part of their legacy.

On that cool morning in 2008, I was told that the young woman undergoing her puberty ritual would emerge from her hut at exactly daybreak. We all hurried along the jungle pathways to arrive on time. On the way there, I asked Chief Cesar Francisco Quinchuya’s wife, Olinda Quinchuya, about her own ponapnora experience.

“When I was 12, I was confined for five whole months,” Olinda Quinchuya said. “Nowadays, girls are only shut in for one or two months because their schoolteachers protest that they are missing too much of the school year.” She went on, “But it is important for Yanesha’ women to do their ponapnora, because otherwise, they become old very quickly; they lose all their teeth and their hair turns white.” In pointing to the specifics of the ritual, she explained, “When the ponapnora woman comes out, it is important that she does not look at anyone—and that no one looks at her—or else she will lose all of the strength she has accumulated in the time she was inside the hut.”

We arrived at the ritual location: a one-room leaf-walled hut that had been constructed on a homestead on a remote hillside. Around two dozen villagers gathered and waited quietly. As the sun began to light up the yard, the chief’s father stood up and said it was time. I heard a loud cracking sound as the young woman and her female attendants broke down the walls of the enclosure.

A group of women and girls of all ages emerged in a long line, holding hands and dressed in traditional Yanesha’ robes. Some of them had intricate designs painted on their faces and arms with natural dyes. They circled the hut, walking slowly. The second in line was the ponapnora woman, her head covered by a cloth so she could not meet anyone’s gaze. Her arms were paler than those of her companions; she had not seen any direct sunlight for a month.

Her isolation may strike some as cruel, but it is not felt that way here. In various parts of the world, such as in some villages in Nepal, menstruating women are considered impure; they can be banished to isolation during each menstrual cycle and face stigma and dangerous conditions. For the Yanesha’, the period of isolation happens only once in a woman’s lifetime and is considered a necessary hardship rather than a punishment; the onset of menstruation is celebrated as a life transition and the right time to learn subsistence skills.

In the celebration I witnessed, the women and girls entered the family’s house and soon came out carrying disposable plastic plates piled high with food for everyone. The modern plates seemed out of place; they must have been hard to get. The women served large chunks of roasted meat, cooked manioc roots (a bland, starchy staple commonly called cassava elsewhere), and a fermented manioc root drink known as co’nes in Yanesha’ (or masato in Spanish). After the meal, the female attendants whisked the ponapnora woman up the mountain to harvest more manioc. I was told that as a woman, I must go too.

The women hung their robes neatly on branches so they wouldn’t get soiled. Wearing secondhand T-shirts and spandex leggings, they started chopping down the manioc trees with big machetes. Out of earshot of the men, I asked them about their ponapnora experiences. One woman in her 50s laughed and told me: “Ha! I used to escape from the hut when my parents were out working in the fields. I would crawl into the house and eat manioc with salt. I was not allowed, but I would do it anyway.” The women all chuckled at her audacity.

“When an important cultural ritual disappears, a community loses a part of its identity.”

“Girls today are too afraid to do ponapnora,” a woman in her 60s observed. “They are afraid of being inside the hut, away from their friends for so long,” she explained. “Most of them love to play volleyball, and they hate missing a month of sports.” A few women laughed about that too.

“After elementary school, many girls go to the city to work as nannies when they are only 11 or 12 years old,” an elderly woman commented. “They are not in the jungle anymore when they get their first period. In fact,” she added, “sometimes her family only finds out that she has become a woman when she comes back from the city years later with a baby. By then, it is too late to do ponapnora!” Some of the women nodded solemnly.

After the feast, I learned that it is a tradition for people to playfully attack one another with huge thorny plants, which, they say, stops laziness from setting in. (The plants are known as shor in Yanesha’ or chalanka in Spanish.) “Good for the joints!” said one woman. “It prevents arthritis!” said another. With loud shrieks, the women and men attacked one another, chasing each other in mad circles and rubbing the plants on each other’s arms and legs. Soon, two teenage boys were swatting at my neck. I would continue to find little shards of chalanka thorns lodged in my skin for days after.

Men grabbed their drums and sang and walked in intricate patterns around the yard. I noticed that the older women knew how to correctly sing the songs, while the younger ones imitated them, mouthing the words. The ponapnora woman alternated between singing, dancing, and serving buckets of fermented manioc drink to the guests well into the afternoon. As I stood nearby, pitifully tending to the chalanka welts on my neck, a woman in her mid-60s approached me and spoke eloquently about her stance on ponapnora.

“It is crucial for the health and well-being of every Yanesha’ woman who lives in the jungle,” she said. “Through the hardship of the enclosure, she learns patience, how to endure pain. By using the medicinal herbs, she becomes strong and resistant to illnesses. She learns how to weave, how to sing,” she explained. “But nowadays, the young ones don’t need to learn how to make our clothes or sing our songs anymore. And some families think that the ritual is outdated,” she added. For some families, it is seen as too expensive and undesirable to spend time away from school and work. “That’s why you’ll see fewer and fewer girls doing their ponapnora,” she said.

When an important cultural ritual disappears, a community loses a part of its identity. Ponapnora is like a boot camp during which a young woman learns about her heritage and taps into her own strength to acquire the skills that will allow her to thrive in a jungle environment. Ponapnora has encoded centuries of ancestral wisdom into one event. While the practice may fade, it is my hope that women’s collective memory, as well as accounts from visiting anthropologists like myself, will help preserve knowledge of this tradition for generations to come.

After the festivities, I headed home with the chief, his wife, and their two young daughters. I asked if their children will do ponapnora one day. Olinda Quinchuya told me that they could only afford to host the celebration for one of the girls. I reflected on the difficult choices they must make as parents.

I lifted one of the tired girls onto my back and kept walking.

* This piece draws on material from the author’s master’s thesis.