How the Opioid Crackdown Is Hurting Chronic Pain Patients

Madeline’s earliest childhood memory was of pain. [1] [1] To protect people’s identity, all names except the author’s and Dr. Kline’s are pseudonyms. She was visiting the zoo with her family and started to cry because the stabbing, throbbing pain in her legs was so intense she couldn’t walk anymore. She was later diagnosed with childhood osteoarthritis.

When Madeline entered puberty, she began experiencing exceptionally debilitating and painful menstrual periods. At 15, she was diagnosed with endometriosis.

Now in her mid-30s, Madeline told me prescription opioids allow her to hold a job and enjoy time with friends and family without spending days in bed recovering from the effort. But recently, her doctor became concerned about rising opioid misuse and forced her to cut back on her medication.

“I’ve had to stop working because of this reduced dose I’m on,” she said. “My car is gone. I feel like my life is slipping away, bit by bit. All I have now is the pain.”

Stories like Madeline’s are becoming increasingly common. Some chronic pain patients have taken their own lives after being tapered off or cut off from their prescription opioids, leaving them in unendurable misery, according to Dr. Thomas Kline, a North Carolina-based primary care physician who maintains a list of such suicides. Two other physicians also reported on these deaths in Slate. Madeline said if she lost access to opioids, she fears she might make the same choice. “I’d be lying if I said the thought hadn’t occurred to me,” she said.

Madeline and other chronic pain patients trace their difficulties with reduced or discontinued prescription opioids to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2016 Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain. The document was a response to the nearly 400,000 overdose deaths involving prescription and illegal opioids in the U.S. between 1999 and 2017. The CDC’s vision was commendable and simple: Curtail the number of opioid prescriptions, and the number of opioid-related overdoses would presumably also drop.

Often missing from the discourse are the 18 million Americans who rely on opioids to manage chronic pain.

But the aftermath of the guideline has been far more complicated. That’s due in part to a “misapplication” of the CDC’s recommendations, according to a November 2018 resolution from the American Medical Association. Doctors afraid of losing their licenses are pulling chronic pain patients off their opioids. Many states and pharmacy chains are limiting people to a three- to seven-day supply of the painkillers. Without their medications, some patients are deteriorating so much they have to be hospitalized or are turning to risky alternative procedures.

Yet opioid-involved overdose deaths continue to skyrocket.

Often missing from the discourse on the opioid epidemic are the 18 million Americans like Madeline who rely on opioids to manage chronic pain. These people feel they have been unfairly labeled as addicts and denied a voice in policy decisions at the federal and state level, in the doctor’s office, and at the pharmacy. As a result, many argue, their lives have been completely transformed by recent policy changes.

These individuals are the focus of fieldwork I conducted at a Boston-area chronic pain support group while I was an anthropology master’s candidate at Brandeis University in 2018 to 2019. As someone living with chronic pain myself, I empathize with their struggles and was surprised by how welcoming, generous, and helpful the community is.

By listening to their stories, perhaps policymakers and the public could come to a more nuanced understanding of the often-misunderstood opioid crisis—and implement policies that work better for everyone.

Earlier this year, I had lunch with Danielle, a member of the support group. In her mid-60s, Danielle has relied on opioids for 20 years. Initially, she suffered a severe back injury, which became exacerbated by repeated damage. Recently, osteoarthritis began triggering extreme pain and stiffness that starts in her joints and spreads throughout her muscles. She also has spinal stenosis, a condition in which the area around the spinal cord becomes compressed, sparking intense back and neck pain and muscle cramping.

Danielle and I discussed the way legal and biomedical experts often frame opioid use and chronic pain. She mentioned times she has heard people in positions of power talking about chronic pain patients who rely on opioids and implying that they all misuse their medication.

“These people are making decisions about us, and they have no idea what they’re talking about,” Danielle said. “And they don’t freakin’ care. They don’t even want to take the time to find out about things. They just say, ‘Oh, it’s prescriptions that are causing addiction.’”

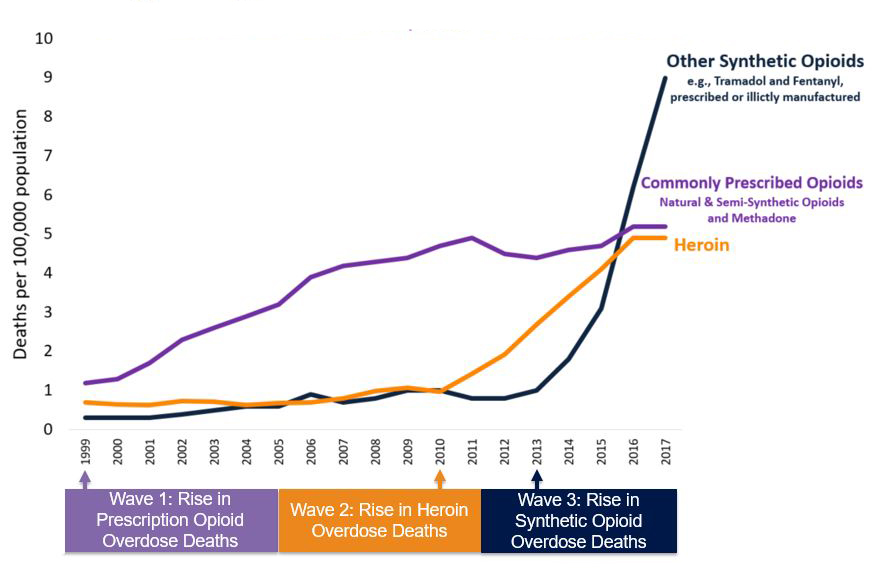

In fact, the opioid crisis in the U.S. is far more complex. Deaths involving illicit and prescription opioids rose from 8,048 in 1999 to 47,600 in 2017. According to the CDC, this opioid overdose tsunami can be separated into three distinct waves.

The first wave of deaths rose steadily starting around 1999 and was largely linked to commonly prescribed natural and semi-synthetic opioids, including oxycodone (such as OxyContin) and hydrocodone (such as Vicodin). These overdoses were generally blamed on a rise in painkiller prescriptions that peaked in 2012, when medical providers issued an average of 81 opioid prescriptions per 100 people, though in some states it was as high as 144 prescriptions per 100 people. As of 2016, an estimated 2 million Americans had a substance abuse disorder involving prescription opioids.

A civil trial is underway involving around 35,000 plaintiffs accusing pharmaceutical companies and distributors of flooding the market with opioids such as oxycodone and fentanyl, and not informing doctors and patients about the drugs’ addictive and dangerous nature. The lawsuit also accuses pharmacies, professional medical groups, and individuals of overprescribing to patients who were abusing or selling the narcotics on the black market.

In the next wave, which started around 2010, well-meaning national initiatives to crack down on this overprescribing prompted some opioid users to turn to heroin. Overdoses from the street drug crested beginning around 2015.

The third (and worst) wave of deaths is driven by synthetic opioids—namely fentanyl, which is around 50 times more potent than heroin. Fentanyl is available by prescription, but experts attribute the spike in deaths largely to illicitly made fentanyl. Because fentanyl is cheaper and easier to produce than many natural and semi-synthetic opioids, many illegal manufacturers began mixing it into other drugs like heroin and cocaine. Around 2013, overdoses caused mainly by this illicit fentanyl shot up and now far surpass deaths due to common opioids and heroin.

The staggering number of lives lost to fentanyl and its analogues—more than 28,400 in 2017 alone—includes a variety of demographics and causes. The majority were men and people of both sexes between ages 15 and 34 who took one or more other drugs, such as cocaine or heroin.

And the most common form of prescription opioid misuse is diverted opioids—pills stolen or obtained without a prescription. Danielle has personal experience with this. While she takes her medication as directed, her brother—who started using opioids before Danielle was prescribed them—once stole a bottle of her medication when he was unable to buy pills illicitly.

Yet despite differences in causation and trajectory, all of this gets swept under the term “opioid epidemic.” And the chronic pain patients who rely on opioids to live a life they find productive and meaningful are swept along with it.

Politicians and policymakers are “using us as scapegoats in the opioid crisis,” Danielle said. Lynn, another of my informants, said: “They don’t want to deal with the fact that their drug war is a failure. People are still getting high. Blaming people like us for overdoses is easy because we’re dependent on opioids. We’re captive to the system, which, right now, feels like it’s trying to kill us by refusing to treat our pain.”

I first met Lynn in the summer of 2018, and I instantly recognized her tall, slender frame as I entered the sunny café. She had sent me pictures showing her dislocated joints and the distinctive white scarring that mars her skin. Lynn suffers from Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, a connective tissue disorder that makes her joints loose and unstable, her skin excessively stretchy and prone to scarring, and her internal organs extremely fragile. Because Lynn’s joints dislocate spontaneously and often, she experiences what she calls “acute pain on a chronic basis.”

Lynn was diagnosed after the opioid epidemic was widely publicized and the CDC guideline was released. The guideline recommends physicians treat patients with other therapies before resorting to opioids. So Lynn was first given a litany of medications that had no effect on her pain. One of those, gabapentin—an anti-seizure and nerve pain med that can induce euphoria—is considered less addictive than opioids but can still lead to misuse and overdoses. It is even sold by some drug dealers on the street. Gabapentin did nothing for her pain and caused her blood pressure to drop dangerously low.

Lynn kept track of each medication she tried, along with its efficacy and adverse effects. Each time she saw a doctor, she brought a copy of the document so they wouldn’t immediately question why she was asking for opioids. In the end, she says, “it took a letter from my geneticist to my primary care doctor for him to finally write me a prescription for hydrocodone.”

Lynn’s experience is not isolated. While the CDC guideline was intended to provide nonmandatory suggestions for primary care physicians, in practice it is often being implemented in ways that go beyond its intent. Doctors are under pressure and suspicion from regulatory boards and the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, and some assume the guideline will soon be codified into law. To protect themselves, many physicians are dropping their chronic pain patients, tapering them off opioids against their will, or refusing to prescribe them painkillers.

Mary, another member of the chronic pain support group, had been a manager of a national grocery store chain but was forced to leave her job because of her pain. When her former doctor retired, Mary explained, “the first thing the new doctor said to me was, ‘Oh, you’re on opioids? I’m not gonna prescribe those.’ It didn’t matter that my life literally depended on them.” Since then, Mary’s life has been transformed from the one she had expected into one of disabling, endless suffering.

“I have a legitimate prescription, but the pharmacists at CVS and Walgreens refused to fill it,” said Danielle.

Even though the 2016 guideline was not meant to be legally binding, 26 states have enacted laws limiting opioid prescriptions. Most of these went into effect in 2017 or later. While many laws are aimed at new acute pain patients, long-time chronic pain patients are frequently subjected to the same restrictions.

In addition, several national pharmacy chains have instituted opioid dispensing policies based on the guideline. For example, CVS pharmacists can refuse to fill opioid prescriptions exceeding 90 morphine milligram equivalent doses per day until they call the prescribing physician and determine whether the amount can be reduced.

Danielle said that a couple of years ago, she went from one pharmacy to another because “no one would fill my script. I have a legitimate prescription, written by my doctor, but the pharmacists at CVS and Walgreens refused to fill it.” She added, “How do they even have that right?”

Chronic pain patients currently have a limited voice in opioid policymaking decisions. When the CDC guideline debuted, numerous advocacy groups complained that chronic pain patients, consultants, and physicians were not adequately included in the drafting process. According to the American Cancer Society, the entire process lacked transparency, and the public was given only 48 hours to comment.

Small improvements are starting to occur. In 2018, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services appointed a chronic pain sufferer and pain patient advocate to its Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force, which was convened in part to propose updates to the CDC guideline. The task force’s report, released in May 2019, recommends a “balanced, individualized, patient-centered approach,” including more time spent between clinicians and pain patients to develop a plan for enhancing quality of life.

In March 2019, more than 300 medical experts signed a letter to the CDC addressing the “widespread misapplication” of the guideline. They asked the CDC to evaluate the guideline’s impact and investigate reports of suicide and increased illicit drug use. They called on the organization to “issue a bold clarification” of its recommendations regarding opioid dosage, tapering, and discontinuation. As a result, the Department of Health and Human Services issued new guidelines in October encouraging doctors to involve patients in decisions about opioid tapering and consult with them to ensure they are not experiencing adverse side effects.

In addition, several patient advocate groups are working to magnify the voices of those afflicted with chronic pain. A movement called the Don’t Punish Pain Rally has organized nationwide demonstrations. Another group protested outside the CDC headquarters in June 2019.

And though many chronic pain patients try to distance themselves from those who misuse prescription and illegal opioids, some people are calling for the two factions to combine their efforts to shape policy changes that benefit everyone. These changes might include improving access to affordable mental health care and recovery programs, reducing the cost of the overdose-reversing medication Naloxone, providing drug users with fentanyl test strips so they can determine if their drugs are laced with illicit fentanyl, or efforts to reduce stigma against all opioid users.

Meanwhile, many chronic pain patients remain uncertain and anxious. Danielle eventually found a local pharmacy to fill her prescription, but she fears losing access to pain medication. “I can’t work without my medication,” she says. “I can’t travel. I can’t spend time with my family. I’d rather die than go back to no opioids, or be tapered down. I have no quality of life without it.”