What Ended This Hub of Ancient Maya Life?

This article was originally published at The Conversation and has been republished with Creative Commons.

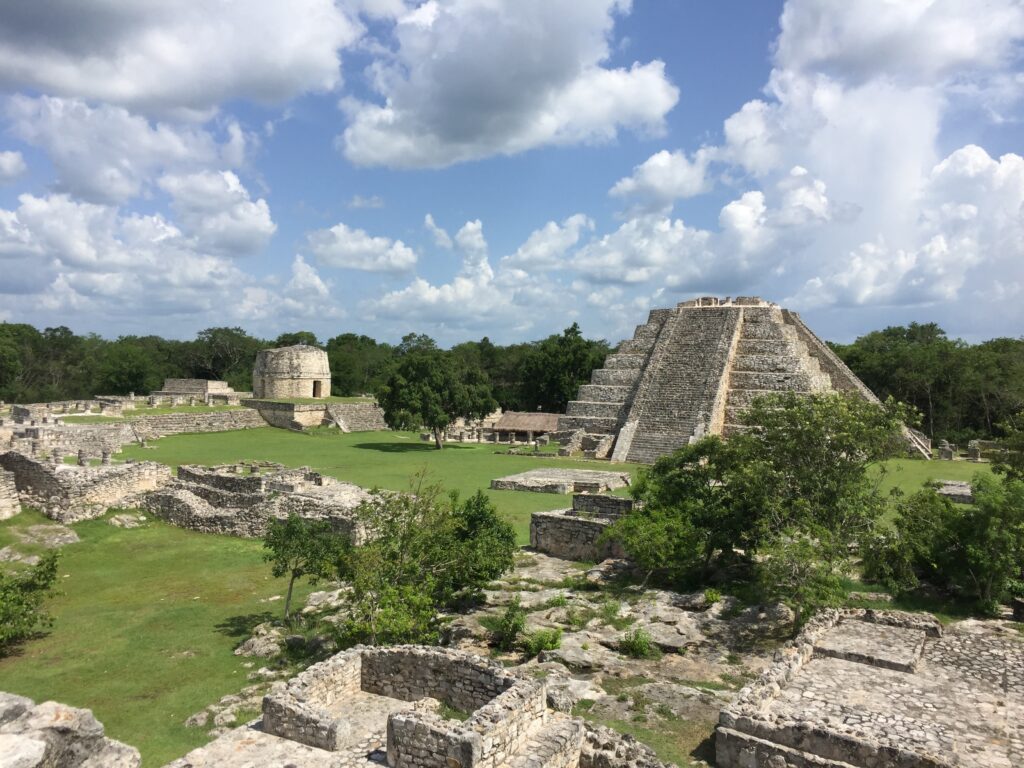

The city of Mayapán was the largest Maya city from approximately A.D. 1200 to 1450. It was an important political, economic, and religious center, and the capital of a large state that controlled much of northwestern Yucatan in present-day Mexico.

When the Spanish arrived in the early 1500s, Mayapán was fondly remembered, and Maya proudly claimed descent from its former citizens. But inherent instability meant that it was doomed to fail.

Or so the story went. This narrative has influenced views of this important city, and this period of Maya civilization more broadly, for some time.

In a new study, my collaborators and I show that warfare, collapse, and abandonment at Mayapán were not inevitable. Instead, they were exacerbated by drought.

Traces of a massacre

Experts from a wide range of fields worked together to piece together this story. The team included archaeologists, biological anthropologists, geologists, and paleoclimatologists.

Archaeologists led by Carlos Peraza Lope, of the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia of Mexico, and Marilyn Masson, of the University at Albany–State University of New York, have been investigating the ruins of Mayapán intensively since 1996 and 1999, respectively. Intermittent work has been going on at the site since the 1950s.

Researchers have long suspected that Mayapán collapsed violently, based on early colonial documents. These records describe a revolt led by the noble Xiu family that resulted in the massacre of the ruling Cocom family.

When archaeologists from the Carnegie Institute of Washington started to investigate the site in the 1950s, they were not surprised to find buried bodies that had not been given the usual respectful funerary treatment.

Desecration and destruction

I am a bioarchaeologist, which means my job was to look for evidence of trauma in the skeletons that may have contributed to the deaths of these individuals. This evidence would support the idea of a violent collapse of the city.

Most burials lacked evidence of violence. However, some exhibited injuries such as embedded arrowheads, stabbing wounds, or blunt force trauma to the skull.

The signs of violence were concentrated in important contexts at the site and found in association with evidence of desecration and deliberate destruction. It seems some of the site’s own elite inhabitants had been the targets of violence.

Rising violence

To find out when this conflict occurred, and how it related to changes in climate, required a large number of high-precision radiocarbon dates and paleoclimate data from the vicinity of Mayapán.

These analyses were carried out in the labs of Douglas Kennett, of the University of California, Santa Barbara; David Hodell, at the University of Cambridge; and colleagues.

As a result, we now have more radiocarbon dating information for Mayapán than for any other Maya site.

Paleoclimate data, meanwhile, was obtained from a stalagmite recovered from a cave directly beneath the site’s principal temple pyramid, which was dedicated to the feathered serpent deity Kukulkan.

These analyses revealed that episodes of violence became more common later in the site’s history, corresponding with evidence of drought that began in the late 1300s and continued into the 1400s.

One mass grave, in particular, recovered in Mayapán’s most sacred precinct at the foot of the temple of Kukulkan, appeared to date to around the time of the city’s purported collapse in the mid-1400s. Remarkably, this was confirmed through radiocarbon analyses, corroborating historical accounts of the site’s violent overthrow at this time.

Drought and decline

But the story does not end there.

Radiocarbon dating also provided the surprising result that Mayapán’s population started falling after approximately A.D. 1350. Indeed, the city was already largely abandoned by the time of its famous collapse in the mid-1400s.

It may be that as drought continued through the late 1300s, the residents of Mayapán started voting with their feet.

After Mayapán’s fall, the city’s former inhabitants returned to their ancestral homelands in different parts of the Yucatán Peninsula. By the time of Spanish contact in the early 1500s, the peninsula was divided into a number of independent provinces, some of which were thriving.

Climate migration

Although from a vastly different time and place, our study contributes to current efforts to combat global climate change.

When environmental conditions were favorable, populations expanded. But when conditions deteriorated, this put pressure on social and political institutions.

Mayapán’s people migrated away from the city to cope with the change in climate. While migration may be less of a solution in the face of today’s climate change, due to global population levels, climate refugees are expected to rapidly grow in number without significant action by governments and citizenry alike.

Big questions, big collaboration

To address big questions such as this requires a level of multidisciplinary collaboration that is difficult to achieve but essential.

Importantly, local Yucatecan Maya communities have been integral to this process. Inhabitants of the equally ancient town of Telchaquillo, located just outside Mayapán, have contributed to this work in innumerable ways, including excavation, artifact cleaning, processing, and analysis.