Want to Make Academic Writing More Readable? Ask a High School Student.

Athalia McCormack, a New York City public high school student, and Danna Rojas, an undergraduate at Fordham University, made their way to the front of the classroom. The audience of 40 high schoolers, undergraduates, and professors cheered and pounded on their desks in support. As the room quieted down, Athalia and Danna launched into a 90-second pitch.

The topic was a subject they had known little to nothing about three days earlier: linguistic anthropology.

Athalia began by asking the audience to imagine how it would feel to be kids living in New York City with undocumented family members. They told the story of a fifth-grade student named Aurora (a pseudonym), who often had to bear the responsibility for protecting her family from questions about their citizenship status. In school, Aurora avoided talking about immigration because it might put her undocumented loved ones at risk. She shut down conversations among her peers and refused to participate in classroom activities on the topic.

Athalia and Danna concluded their pitch, based on original research by audience member Ariana Mangual Figueroa, with a powerful call for empathy: “By learning about undocumented students and immigrant children … by listening to them and witnessing their real experiences, we can break through polarizing debates about immigration and advocate for these students without depending on them to carry the burden.”

“The flourishing of one is the flourishing of all,” Athalia and Danna concluded.

Murmurs of appreciation rippled through the group and grew to resounding applause. Hearing their pitch gave the audience goosebumps.

Everyone in the room was participating in the Demystifying Language Project (DLP), a research and social justice initiative to make scholarship on the politics of language available in public high schools. At that moment, we were all partners in a profound conversation about language and power.

For more on language, power, and education, read on from the SAPIENS archive: “Why I Ask My Students to Swear in Class.”

As linguistic anthropologists, we co-direct the project with five other interdisciplinary scholars. [1] [1] Ayala Fader is the founding director, and the co-directors (in alphabetical order) include Lynnette Arnold, Justin A. Coles, Britta Ingebretson, Mike Mena, Johanna S. Quinn, and Bambi B. Schieffelin. The DLP works to share with teachers and students what we know from our research: “standard language” is not clearer or better; it is simply the language of powerful institutions and people. Research in public schools also tells us that standardized curricula marginalize those who speak other languages or varieties of English by valorizing only “proper” or “academic” language.

Anthropological scholarship can make visible the often-invisible ways that unquestioningly making standard language the default in classrooms reproduces inequalities. But scholarly writing about language can alienate nonacademic readers, especially young people, because it tends to be written exclusively for other scholars.

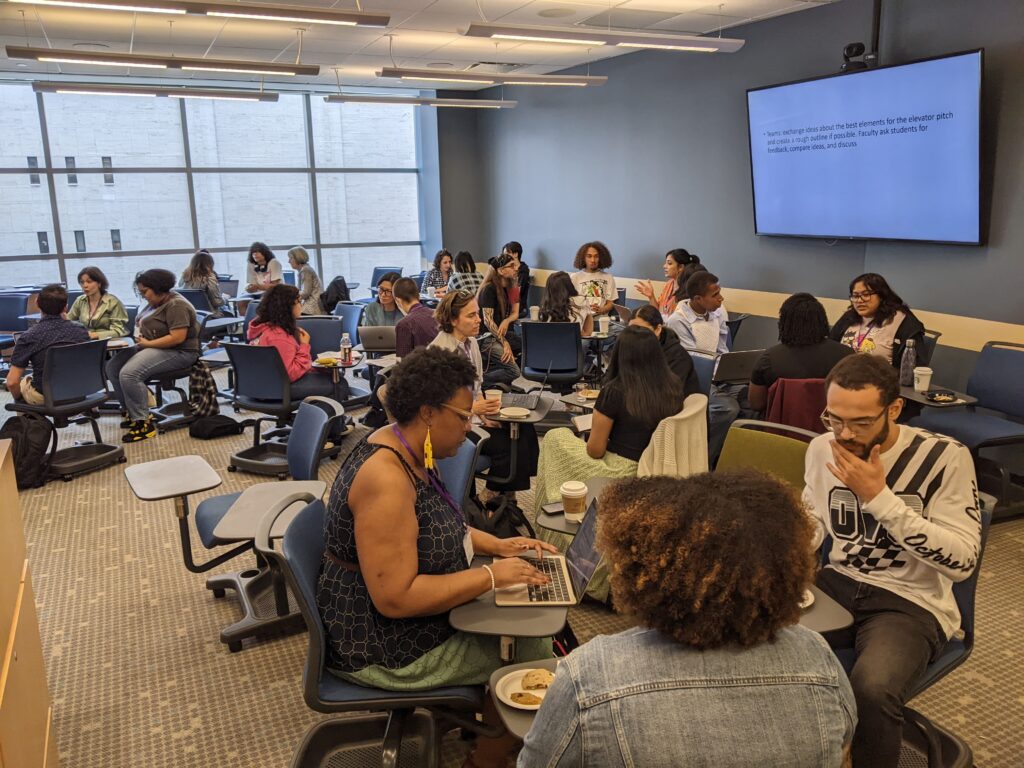

To make this scholarship available, we wanted to give anthropologists the opportunity to learn from high school students directly about how to write in a way that speaks to teens’ lives, especially in linguistically and racially diverse contexts like New York City. Athalia and Danna were two of 24 high school and undergraduate students selected from the city’s public high schools, Fordham University, and the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, to participate in a three-day writing workshop in 2023. [2] [2] This workshop was supported by the Wenner-Gren Foundation (which funds SAPIENS), the Spencer Foundation, and Fordham University.

The students joined 12 established anthropology professors with expertise in language and power. Participants worked in teams of three—an author/professor, an undergraduate, and a high schooler—to transform each author’s original research article into a short piece that high school students would want to read. Linguistic anthropologist and DLP co-director Mike Mena refers to this process of making academic writing more accessible to public audiences with the musical term “transposition,” likening it to “changing the key of a song.”

WHO’S THE EXPERT?

By breaking down academic hierarchies that structure who produces knowledge, the DLP aims to change who has access to that knowledge and highlight why it matters. This isn’t easy. For the writing workshop, we decided to try something radical to explode those hierarchies, beginning with the recognition that high school students are experts on their own reading.

The Central American social justice concept of “accompaniment” inspired us to structure workshop activities that flipped traditional power dynamics to foster interactions where everyone brought their own expertise to our shared project.

For example, in one of the first activities of the workshop, high schoolers presented to the whole group on how they liked to read, what spoke to them, and what made them stop reading. The next day we drew on students’ social media expertise, asking them to make TikTok videos about the article they were transposing or their experience in the DLP.

On the first day, each team worked to create a 90-second “elevator pitch” that included four things: the most important idea from the original article, how the author did the research, one supporting ethnographic story, and the “so what” message. As they worked together, authors explained their main intention, talked about their fieldwork, asked students questions, and defined key words and ideas. The students asked a lot of questions of their own and made suggestions based on their understanding and interest.

That afternoon, getting ready to give their elevator pitches, the authors were understandably nervous to get up in front of the group. We academics don’t usually give short, snappy versions of our research. Trying again to flip the power hierarchies, we asked students to vote for the winning pitches. The winner received a glamorous diamond tiara.

Students judged the academic authors based on what was interesting and clear to them as the intended audience, again making them the experts. The next day, students delivered their own versions of elevator pitches in teams, like Athalia and Danna did, receiving enthusiastic applause and appreciation.

GETTING PERSONAL

Before the workshop, we thought transposition was mainly about removing unnecessary jargon, picking one key idea with an ethnographic example, describing research methods, and cutting down length. And indeed, the workshop helped authors develop these writing strategies and explore different ways of writing. In their DLP essay about bilingual students, for instance, Nelson Flores and Jonathan Rosa chose to address readers directly in their first sentence: “How would you feel if someone told you that you didn’t know any language?”

But ultimately, we found that making academic writing more accessible was only part of the workshop’s success. Equally important was how the workshop changed the social dynamics of learning by flattening academic hierarchies.

Students became invested in “their article” once they felt the sense of excitement and commitment that the original research and writing inspired in the authors. For example, in her DLP essay about language and power in legal contexts, Sharese King analyzed the trial of George Zimmerman, who was charged with killing Trayvon Martin, an unarmed Black teenager, in Florida in 2012. Zimmerman was ultimately acquitted of the crime—a decision that many saw as a miscarriage of justice.

King’s work analyzes how jurors largely disregarded the testimony of a key witness, Rachel Jeantel, because she used African American Language or “Ebonics” on the stand. King had done the research and co-written the original article years ago, but in the workshop, she was reminded of why she cared. The research was personal, she said, because these kinds of racist judgments could just as easily happen to her or her family. This personal connection, in turn, drew the students into her piece because they recognized that racist judgments about language could impact them too.

For the students, working with “their” author led to new and empowering insights on language, education, and justice. Undergraduate Sitara Vaidy, for instance, worked with the author Barbra Meek on the essay, “What Makes the Indian Sound Indian,” which critiques harmful stereotypes of First Nations characters in Disney movies. After working on the article and watching Pocahantas again, Sitara shared that she was shocked she hadn’t picked up on the racialized linguistic stereotypes in the animated film before.

DISRUPTING HIERARCHIES THROUGH LANGUAGE

The insights we gained about language, culture, and power went beyond the academic content of the workshop; they came out of our efforts to dismantle educational hierarchies that are reinforced through language. Even sitting with their teams during lunch provided a chance to disrupt these assumptions.

When Danna and Athalia ate lunch together that first day with their author, Ariana Mangual Figueroa, Ariana casually began to use English, Spanish, and Spanglish. The students responded in turn. In her bio for what would be the first article published, Ariana listed Spanish, English, and Spanglish (with an explanation) as the languages in her life. After that, we noticed many other DLP team members also began including “Spanglish” or “African American Language” in their bios, implicitly acknowledging that their many ways of speaking were assets not deficits.

Being part of this process, we were deeply touched to see how the writing workshop fostered students’ academic self-confidence, which was reflected in the impassioned and insightful pitches they delivered. Their collaboration directly shaped the final short essays that now appear on the DLP website as an open-access educational resource for all to use. Next, we plan to use the DLP resources for critical language courses, where students and teachers study the scholarship of linguistic anthropology and conduct research on their own language(s).

We brought the students together again for the website’s launch in May 2024 and invited Athalia and Danna to tell the audience about their experience. Athalia described the excitement of being at Fordham and getting to work with an author who is “known for doing these big things” as “just a 16-year-old” from the Bronx.

“For me to be sitting in the room,” she said, “to have my name be on the article, and to have a relationship with both Danna and Ariana. It was just really, really cool!”

This publication was made possible by the Demystifying Language Project, a social justice and research initiative to make scholarship on the politics of language available in public high schools. Many thanks to the high school students, undergraduates, and scholars for their willingness to creatively participate in the DLP experiment.

Correction: August 20, 2025

A previous version of this story described Trayvon Martin as “a young unarmed Black man.” In consultation with the authors, this has been updated to “an unarmed Black teenager” to better reflect Martin was 17 years old at the time he was killed.