Since its emergence in 1960s Harlem, the LGBTQ+ “ballroom scene” has expanded into a transnational subculture. For outsiders, understanding how a ball functions can take time.

Join linguistic anthropologist Dozandri Mendoza as they “walk” us through a night at a kiki ball in Puerto Rico. They introduce us to DJs, commentators, performers, and the Boricua Ballroom children who are refashioning the techniques of their trans-cestors. Dozandri guides us through both the expectations of those on the sidelines of the ballroom runway and the anticolonial political meanings behind the Puerto Rican ballroom scene.

Dozandri Mendoza is a Ph.D. candidate in linguistics at the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB). Their doctoral research focuses on trans forms of creative expression in the Puerto Rican ballroom scene. Dozandri explores the representation of Puerto Rican linguistic practices in the archive of ballroom history. They also examine what verbal and embodied art forms such as reading, throwing shade, commentation, and walking a category teach us about diasporic memory, decolonial critique, and trans survival. Their work centers around a multimodal and performance-based ethnographic installation called the “Kiki Ball del Palabreo” held in Puerto Rico in 2023. Dozandri’s research has been supported by a Society for Visual Anthropology/Lemelson Foundation Fellowship, the Duberman-Zal Fellowship from the Center for LGBTQ+ Studies, and grants from the Interdisciplinary Humanities Center at UCSB.

Check out these related resources:

- Laborivogue (Host of the ball and ballroom performance collective in Puerto Rico)

- Afroponka Fest (Festival of which the Black is Ponka Kiki Ball was a part)

SAPIENS: A Podcast for Everything Human is produced by Written In Air. The executive producers are Dennis Funk and Chip Colwell. This season’s host is Eshe Lewis, who is also the director of the SAPIENS Public Scholars Training Fellowship program. Production and mix support are provided by Rebecca Nolan. Christine Weeber is the copy editor.

SAPIENS is an editorially independent magazine of the Wenner-Gren Foundation and the University of Chicago Press. SAPIENS: A Podcast for Everything Human is part of the American Anthropological Association Podcast Library.

This episode is part of the SAPIENS Public Scholars Training Fellowship program, which provides in-depth training for anthropologists in the craft of science communication and public scholarship, funded with the support of a three-year grant from the John Templeton Foundation.

A Linguist’s Night at the Ball

Eshe Lewis: What makes us human?

Anahí Ruderman: Truly beautiful landscapes.

Nicole van Zyl: The roads that I used every day.

Thayer Hastings: Campus encampments.

T. Yejoo Kim: Eerie sounds in the sky.

Eshe: What makes us human?

Cecilia Padilla-Iglesias: Division of labor.

Charlotte Williams: Colonialism.

Giselle Figueroa de la Ossa: The value of gold.

Dozandri Mendoza: Fun. Dance.

Justin Lee Haruyama: Cultural and social interactions.

Luis Alfredo Briceño González: Hopes for a better future.

Eshe: Let’s find out! SAPIENS: A Podcast for Everything Human

Eshe: Since its emergence in Harlem, New York, in the 1960s, the Ballroom scene has expanded into a transnational queer and trans subculture. It takes time to learn how a ball functions and even those norms can change across cultures. In this episode, linguistic anthropologist Dozandri Mendoza gives me a tour of Kiki Ball in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

And what would an episode featuring a linguist be without a quick note about language. Ballroom has a unique vocabulary that flips the script on many historically offensive terms. The language used in this episode may not be suitable for all listeners, but we do encourage you to keep the context of use in mind while listening.

Eshe: Dozandri, can you please tell me a bit about yourself and your research?

Dozandri Mendoza: Yeah, so my name is Dozandri or Doza. I’m a linguistic anthropologist, really interested in queer and trans performance. I’m originally from Miami, Florida, but with diasporic roots in Cuba and Puerto Rico, which have really informed a lot of my work. So I started in my master’s with research around language, drag, and performance. So how aesthetics influence how we use the voice. In my current doctoral work, I’m really interested in how folks use the body to make meaning in dance performance in the Ballroom scene in Puerto Rico.

Eshe: So, Dozandri, can you help me understand what Ballroom is, you know, where does it come from, and where might people have seen or heard about Ballroom before?

Dozandri: Yeah, so Ballroom is a lot of things. It comes from really at the height of 1980s emergence of drag culture in Harlem between Black and Latinx communities, really Afro-Caribbean communities. And then emerged into what folks might have seen online today, most popularly around voguing, right? That kind of dramatic dance style where folks crash into the floor, spin around, and often are dancing to this really kind of dynamic beat.

They might also know it from shows like Legendary or Pose or the documentary Paris Is Burning, but it’s really more about, you know, a wide variety of performance genres beyond voguing. So things like runway or walking face. It also is really importantly grounded in a family support system. So Ballroom has these different houses where folks have mothers and fathers and children. And that structure is how people prepare for these different performance events. So Ballroom has these events called Balls where folks go and practice these different art forms with their houses or their families.

Eshe: So, I’ve seen Paris Is Burning, but for those who are not familiar with that documentary, could you just give us a brief description of what it is and why it’s so important?

Dozandri: Paris Is Burning was a documentary film around the Ballroom scene at the kind of height, so 1980s moving into the early 2000s era of Ballroom that influenced a lot of what we see today, and it walks you through, similar to this episode, different aspects of a Ballroom night, right? So, it talks about different categories, and it also shows you some of what I call the Ballroom “verbal arts.” So, learning how to read, what’s shade, these things that are kind of a ritual insult practice within the Ballroom scene. And it also breaks down that family structure for folks to understand, um, how Ballroom works and how it’s rooted in this kind of community system. However, there’s been a lot of critiques from within the Ballroom scene around this kind of voyeuristic white gaze by the director Jennie Livingston and what that means in terms of representing Ballroom in the way that it does.

So I think that it’s a super important kind of artifact for folks in the scene to learn about what it was like at the height of this particular culture. But there’s a lot of things that were deleted from the main film. One of those things being, in the deleted scenes, you actually see folks speaking in Spanish and throwing shade in kind of a Nuyorican Spanish that we don’t see in the main film, which I’ll be talking about in my future work. So stay tuned.

Eshe: I know a bit about what Ballroom looks like in big cities like New York. But can you tell me what Ballroom looks like where you are in Puerto Rico?

Dozandri: Yeah, I mean, there’s a lot of similarities, and I think there’s also some differences, right? So there’s still the competitive category structure. A lot of those categories are still walked in Puerto Rico. So, you’ll still see voguing, you’ll see face, and you’ll also see categories that are really specific to the Caribbean, like grajeo, which is kind of like making out.

So, there’s differences and there’s similarities, but I think a lot of what makes Puerto Rican Ballroom so particular is that it often has a political stance of anticolonialism. So a lot of the balls that are hosted in Puerto Rico are really about speaking back to the political status of Puerto Rico and relationship to the U.S. and to a variety of other political causes as well. So you’ll see solidarity markers. Like there was a ball where I was at where there was a Palestine flag at a particular moment where people were thinking a lot about Palestine—walking with Palestine at solidarity marches. And yeah, it’s really about a kind of politic that is embedded alongside the art itself.

Eshe: OK, so, I’m gonna follow that train of thought. You are someone who studies language. So, I guess I’m wondering why study dance and performance, you know, what makes it so interesting to you as a scholar of language?

Dozandri: Yeah, so one of the things that I think is at the core of linguistic anthropology is understanding how people make meaning. And one of those major ways of making meaning is by using language. But we make meaning all the time with different aspects of our bodies, different aspects of how we communicate. Some of that is gesture. Some of that is, you know, the longing gaze we might have toward someone at the club. Some of that is, you know, a wink of the eye. But linguists don’t often study those things

But I became really interested in what happens when we center the body as well. And dance, right? So the dancing body makes meaning, it makes me emotional to become interested in, in how, how does dance, factor into how we make meaning and how we understand how someone, you know, moving an arm in a particular way could elicit an emotion or something like that.

Eshe: Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. Sort of like, you know, words come out of a mouth, which is attached to a body, and so it makes sense that those would be in conversation with each other. I don’t know if that’s a pun, so maybe forgive it.

Dozandri: I wish more linguists agree with you, really. That’s really the core of, I think, how I see things being together.

Eshe: That’s amazing. So, how did you arrive at this particular collaboration with Ballroom in a Puerto Rican context?

Dozandri: Yeah, so it was the pandemic. In 2020, [I] was sitting at home watching a lot of different Ballroom clips on TikTok, and I at the time was doing work on drag. So that was kind of my, you know, entryway into performance-based language research. I came across a TikTok of the Ballroom scene in Puerto Rico, and my dad’s family’s from Puerto Rico. I grew up visiting Puerto Rico, but my vision of Puerto Rico as a queer place was kind of clouded by the diaspora tale about these places being so much worse for queer people than where we currently are in the United States. And I was like, wow, I never imagined that there would be Ballroom in Puerto Rico. I knew there were historical connections, but I was fascinated. I was like, Oh my God, I have to go. And luckily, it aligned with my birthday in 2021, I went to the Pride Ball. It’s kind of the first major ball in the scene in Puerto Rico after the pandemic.

So, it was huge. I got to go there and kind of just experience it without any research context—just go, have fun, dance, listen to the music. And after that I was like, I really need to get in contact with folks in the scene and and figure out what’s going on. Because it was just so fascinating to me as somebody who grew up in the diaspora and, you know, really was fascinated by this queer connection to Puerto Rico that I started to form that night really.

Eshe: That sounds like a really interesting transition for you. And that brings me to my next question, which is what will we be talking about today, and how does it relate to your work?

Dozandri: Yeah, so I guess from that moment, right, that was my first ball and now for, well, it’s not nighttime, but we’re gonna be walking through together a night at the ball from the perspective of how I think about communication.

So, we’re gonna be walking through from the beginning through some categories to thinking about how the ball functions, and really adding in my perspective as a linguistic anthropology scholar of, how does the whole thing work, right? How do people make sense of the complicated dynamics of a ball, right? There’s music, there’s people dancing, there’s people throwing things, potentially wigs. But how does that all make sense, right, as a kind of ritual or a regular kind of practice of culture?

Eshe: OK, well, I have a healthy dose of curiosity and a wonderful guide. So, uh, let’s go to the ball. Let’s start by having me ask you what happens when you arrive at a ball?

Dozandri: We’re gonna first go to kind of the beginning moments of a ball, right? So I want you to just immerse yourself in what it sounds like, what it feels like, what it looks like. Before we get into the nitty gritty.

[Audio from a video clip of the ball begins]

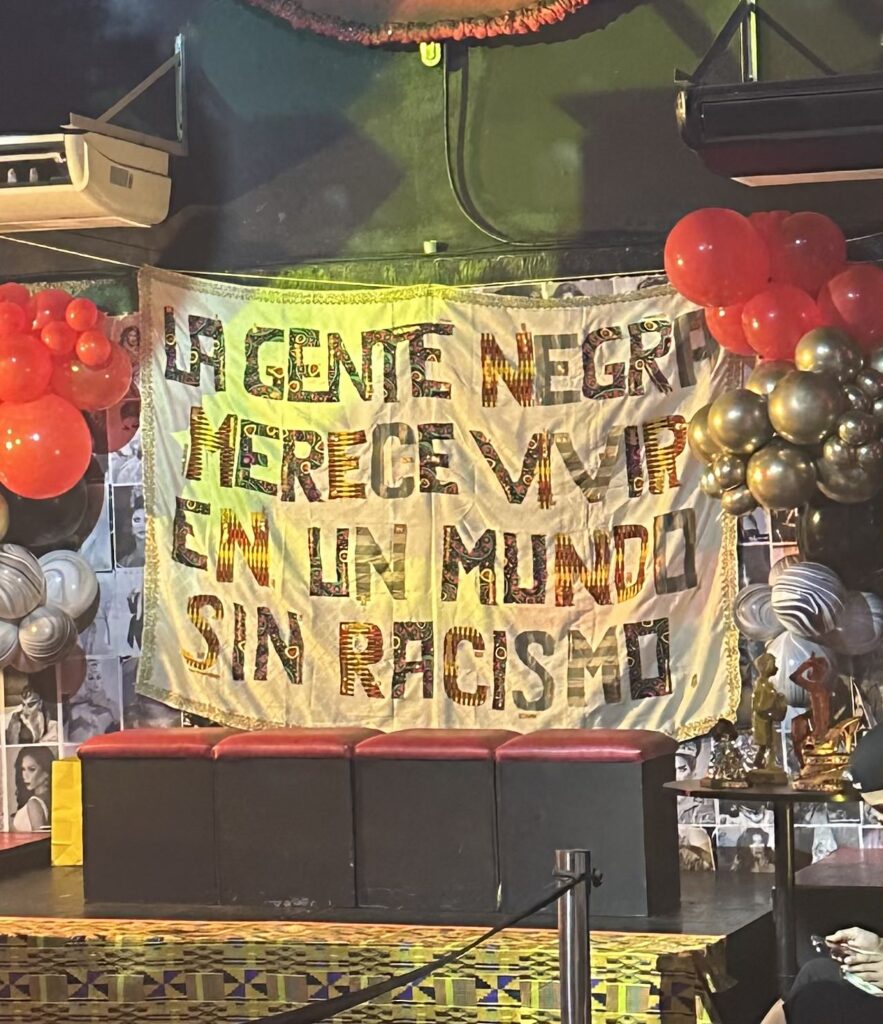

Dozandri (describing the video): This first clip, we’re looking at the Ballroom floor. There’s some shiny disco balls. There’s a poster at the end of the runway that says, “la gente negra merece vivir en un mundo sin racismo.” And there’s two commentators on the mic at the end of the runway floor, cueing us into the DJ, who’s on the stage, on the side of where the spectators are. Those watching the ball.

[Audio from a video clip of the ball ends]

Eshe: All right, so we are in there, the DJ is doing their thing. Now that we’ve got a bit of that entryway context, we’re in the ball. Where do I stand? Who do I interact with?

Dozandri: So when you’re at the ball, you’re normally, if you’re not competing, you’re a spectator. So spectators are those who stand on the sidelines of the runway. And if you notice, it kind of forms a circle. So it’s similar to a lot of other Afro diasporic performance genres like Bomba or some of the ceremonies in Santería, where folks kind of coalesce around this circular space around drums or the beat or someone who’s facilitating the musicality of the event.

So those spectators are those that just, we line up on the sides and wait to see what happens and follow the direction of those that are on the mic, right? So those that are on the mic are called commentators. Commentators are those who entirely kind of guide the runway. So they help folks understand when a performance is supposed to start. They help the DJ cue into the music for when somebody’s performing, and they really help structure the night, right? We follow them for instructions around when people are supposed to walk the next category, when we’re supposed to be waiting until the next category is announced. And they also help us understand each element of the ball. So, they’re also often prompting us with descriptions around what’s to come and what’s to come next.

Eshe: OK. I wanna know how I know when the ball starts?

Dozandri: Yeah. So that first part is called “Legend Stars and Statements.” When we hear LSS called, that’s when we know everybody needs to be in their place, whether on the side of the runway, whether getting ready in the back to walk a category like, all right, I probably only got about 10 minutes before I have to be out there in a wig and my full makeup and my outfit, and be ready.

So, we’re gonna give, uh, some time to think about, and watch what LSS looks like. And again, that stands for “Legend Stars and Statements.” And those same two folks that are on the mic, the commentators, they’re gonna help cue us in to what that really is.

[Audio from a video clip of the ball begins]

Dozandri (describing the video): This next clip, so one commentator is on the mic in a red long dress. The other commentator in a sparkly, shimmery silver dress with an Afro. And they’re both on the mic telling us what it means to walk LSS. Telling us about the importance of contributions of those who have been walking in this particular part of the ball, and that it really has to do with being bien perre or cunty.

[Audio from a video clip of the ball ends]

Dozandri: So, they mentioned LSS is to kind of celebrate those que han hecho un impacto en la escena, right? That have done an impact in the scene. So it’s really, it’s not just the beginning of the ball, but for me, when I understand the way that Ballroom works, this is how we really hold the memory of who’s important, who came before us. So LSS is all about celebrating those who have made contributions either to the different dance forms, so have a signature style that we all know and love. Or it could also be, like they say, folks who have contributed performance labor. So that could be the DJ, that could be the folks who sew the outfits, that could be folks that show up regularly to really make the events happen. And that doesn’t necessarily always have to do with performing. It’s all of the nitty-gritty that makes, you know, this complicated kind of event possible.

Eshe: That’s amazing. I love that. Kind of like honoring your living ancestors kind of thing?

Dozandri: Yeah, yeah. It’s really about, I call this “transcestral citation” in my own work, but it’s about honoring the transcestors and that’s how they arrive on the floor at every ball, right? We recognize what they’ve done for us to be able to walk, you know, in the present. And that constant citation through naming, through how we dance, is really important to how I understand the whole space functioning.

Eshe: Yeah, that makes sense. So what does walking LSS look like?

Dozandri: Yeah, so walking LSS, it’s really important to pay attention to kind of the beat, right, because it’ll also cue us into the style of category that they walk. But I want to show you an example of somebody walking LSS to what the commentators prompt them to do.

[Audio from a video clip of the ball begins]

Dozandri (describing the video): Here we’re watching this beautiful femme in high-heeled khaki boots and a khaki kind of beige dress with these large silver adornments on top of their head walk and be called by the commentators to give LSS. Here they’re giving us a strut to this kind of periodic beat that is signature to the runway categories of Ballroom.

[Audio from a video clip of the ball ends]

Dozandri: So what do you notice about their movement and the beat playing in the background? Like, what does it kind of evoke for you?

Eshe: I don’t know. It kind of feels like, it always feels like disco to me when I get like a higher, more, like a high-energy beat, and I’m thinking about the intro, which seemed a lot more sort of reserved, and now it’s kind of like, this feels like an entry into a show, right? Into an experience. Like this is setting the tone for what’s to come.

Dozandri: Yeah. I love that you mention disco and that high-energy beat and this kind of soft, but repetitive beat is really the base of how runway is walked. What you’re seeing in the clip is not necessarily what folks know Ballroom always for, more famously voguing, right? But it’s this kind of confident walk and model-esque kind of presentation. You can, you can feel the strut through the beat almost. Um, and that’s how you know that this person is probably someone that’s been well known for runway, right? So that’s really what they’re being called onto the floor to perform as an icon in the scene.

Eshe: Dozandri will take me back to the ball after a quick break.

[BREAK]

Eshe: Before the break, linguistic anthropologist Dozandri Mendoza was taking us through a night at a ball in Puerto Rico. Let’s get back to our conversation.

So, this feels like the end of the beginning, right? Like, we’ve walked in, we’ve heard the commentators, we’re in LSS. Can you walk me through a category where people are competing and how that works? I think that’s where we’re going.

Dozandri: Yeah. So, we’re not going to look at runway, but we are going to look at face. So face is my favorite category. It’s the category that I walk in Ballroom. And it’s a full range of steps that we’re going to look at from walking to competing to winning, right? And just to let you know, this is a category that I’ve always gotten my 10s in, which is the thing you want to get. That’s how you, that basically means that you know what you’re doing, but I have not yet won. So, you know, I don’t necessarily know 100 percent what I’m doing, but enough to get my 10s.

Eshe: You’re a star in the making.

Dozandri: A star in progress. Yeah, I think that’s in my Instagram bio, actually.

Eshe: Well placed. Um, so before we get into it, how did you start walking face?

Dozandri: So, when I first started the collaborative part of this ethnographic work, I was meeting regularly with one of the main Kiki house fathers in the scene. So a Kiki house father is someone who runs a house, and he became my main collaborator in this project. And as we were starting to plan this idea of putting on a ball together, so I ended up doing a ball for my actual ethnographic research project. I put together one with the community that was all around language. And he was like, well, if you’re going to do something like this, I need to see you at the practices, girl, like you need to start walking yourself. People need to know you intimately because it’s a lot of trust that’s built on the runway, right, in the circle of the Ballroom. And I started to attend weekly practices of myself, and I tried runway. I tried vogue. Um, and I do know a couple of the elements of vogue, but you know, these knees are not meant for vogue femme. So …

Eshe: We all need to know where we shine.

Dozandri: Yeah, you know, and I had physical limits that were not going to allow me to be out there voguing with the best of the girls. But, as I started to go to these practices, I was kind of enamored by face because, as someone who’s not always outwardly kind of affirmed as a trans feminine person, there was something to in Ballroom that putting on makeup, no matter what my body looked like, I was always affirmed as feminine by walking face. And it was something really, really powerful about that category. And really about the idea of “cunt,” right. So when you walk something like face, and you put on makeup, and you exude this kind of confidence that the category requires, that really was learning the essence of “cuntiness” for me. And that’s really where I built confidence around walking in Ballroom, understanding Ballroom. And that category since then has kind of been my favorite.

Eshe: So, OK, you just said the word “cunt” and “cuntiness.” I think, you know, that word or the root of that word has a very negative connotation in English. And you kind of alluded to it in what you just said, but can you just help me out so that I can get a full understanding of what cunt means in the Ballroom world? Like, it seems like that is something that is positive. Can you talk a bit about that?

Dozandri: Yeah. So there’s a lot of words that I think in Ballroom have undergone this process of resignification or gaining new meaning. And “cunt” is one of them. In the outward world, it’s an incredibly violent word targeted at femmes. And I think femmes in the scene, what they’ve done is created it to be the ultimate kind of positive affirmation of femininity. So it has quite this… it’s what you want to be on the Ballroom floor is to be “cunty” or to be “cunt.” And there’s something really powerful about using this kind of term that was used to degrade women to now be something that anyone can occupy to kind of exude a radical femininity, which is really what “cuntiness” and “cunt” are about.

And it’s also something read off the body, right? Anyone, you know, theoretically could be “cunt” on the floor if you learn how to exude it through the performance of Ballroom categories.

Eshe: OK, so, I guess what I want to know now is what “cuntiness” looks like when walking in a category? Like what does the body look like? What does the face look like? What does this mean in movement?

Dozandri: Yeah. So, for this, I have to kind of take out a little bit about my own expertise in walking face. But I’m going to dive you into what it looks like to walk the face category.

Eshe: Let’s do it.

[Audio from a video clip of the ball begins]

Dozandri (describing the video): We’re at the back of the runway of a face category watching somebody get evaluated by the judges. They have an assist with someone shining a light on their direct face as they point to their jawline and different features that they’re presenting to the judges. The judges in unison all put up their 10s, passing them to the next round of competition of face.

[Audio from a video clip of the ball ends]

Dozandri: OK, so that gives you kind of an idea of what it looks like. It’s complicated because when people are walking, there’s a lot going on. But there’s also the light being shown. Some folks use props. But it’s really about walking up to the judges. That’s the main thing. It’s an up kind of front close category. So it’s not one where you’re using the entire floor of the space. Sometimes in voguing a runway, you have to kind of also work with the crowd. You do in face as well, but you also have to be examined up close to understand how people are really showing off the different features of the face.

Eshe: OK, yeah, that’s a great breakdown of what I just saw. Now, Dozandri, I’m kind of a competitive person. So at this point in time, I want to know, once you’ve walked, how do you win? Right? Like, and how does the crowd know who won? How do we get to those decisions?

Dozandri: Yeah. So, for this particular ball, there’s always a theme, right? So this was about androgynous face inspired by Grace Jones. So it’s not just paying attention to the general kind of repertoire of how you walk in the visual categories. You also have to match the brief in a way of what they’re calling for on that night. So, what I’ll start with is showing you how I walk face on camera, you know, between the two of us.

Eshe: Oh, yes, please!

Dozandri: And I want you to kind of tell me what you notice and then see if you can emulate. So, walking face is all around a couple of different elements to walking face. So, there’s things like skin, angles, teeth, and you really have to exude a type of confidence as well. So, when you’re walking face, you want to highlight kind of the structure of your face, no matter where that structure falls. Things like lining the jaw, the bridge of the nose, show your teeth, you know, pearly whites, and you really are slowly drawing folks to not just structure, right, around the physicality of the face, but also a confidence, right, where I’m not just showing you, it’s like, I know that I’m showing you, and you should be thankful that I am showing you, right, and that’s really the confident aspect of how to walk something like face. So, that’s really how you kind of walk the category. And in terms of fitting the brief, that you could do with makeup, right? Or you do with stylization of different things. So for Grace Jones, you want to emulate one of her kind of iconic eyeshadow looks that give the idea of androgynous face that inspired this particular category. So, that you play with aesthetics that kind of stylize the base of the category, which is the things that I just kind of showed you. And then how do you win?

Eshe: How do I win?

Dozandri: Yeah, so I mean, you got to do all those things that I just showed you, but there’s generally a series of rounds until there’s a final two, right? So when you walk, that’s the first thing you do. What I just showed you is your initial presentation to the judges. And if you get your 10s, you pass the next round, which is always a relief for me because it shows that you do know how to walk the category, and you’ve been affirmed.

The next step though is to be, you know, that girl, or that anything, really. But it becomes harder at that stage because it’s not just about selling it to the judges. Then you might involve the crowd, getting folks to kind of cheer on for you. The room, you can kind of tell who’s starting to pick sides because they get louder for particular performers.

People start to involve themselves on the floor. They’ll point and say, this is the person, right? “Este perre” is the person that you’re supposed to be going for. So at that point, you really have to involve yourself and not just selling to the panel, which is kind of the initial step—walking to the end of the runway and making sure the judges know who you are. It’s bringing folks into creating that energy so that everyone is on your side to be that final person everyone’s cheering for across the different rounds. And then when you make it to the final round, and it’s just you and another person, that hopefully you’re the one that gets the majority votes. It’s a majority rules. It is somewhat democratic, although, Ballroom is messy, and it doesn’t always pan out that way. But it tends to be a democratic voting process with the judges, and whoever gets the majority is the person who wins the grand prize, which, it often is money, but it could also come with a gift certificate or an experience, depending on who’s helping put on the event.

Eshe: OK, so two things are coming up for me. One, there’s a judging panel, but this is also kind of like a group consenting process. So, spectators actually seem to have some sway, right? Like, I think when we normally think about spectators, we think about someone just standing off to the side and not participating, maybe just cheering, but it sounds like spectators in this space also have power to some degree, and a say, and a voice that, you know, that matters in this process, which is fun, I think.

Dozandri: Yeah. I think sometimes in popular representations, you’ll see a one through 10 scale of how to actually get a positive score in Ballroom, but most of the time it’s either 10s, which means that you passed through the first round and you’ve been evaluated successfully as someone who knows how to walk this category or it’s a chop. And a chop, which, you know, showed by the particular gesture of cutting across the neck. That is, you didn’t make it, and you might need to rethink what you were doing there and why you decided to walk that night. But it’s really 10s or a chop. That’s the range. So everyone has to give you your 10s. And just one judge giving you a chop means you’re out of competition.

And I think what you’re picking up on is really important because you can tell on the Ballroom floor who are the spectators that don’t know how to spectate, right? Because spectation or spectatorship sounds like this passive thing in the way that it’s used. But in Ballroom, it’s an active process, so you’re supposed to be also carrying on the beat. So spectators often clap to the structure of the beat of the category, right? To help hype on each person that’s walking and to also help see that there are certain folks that are getting a little bit more energy from the crowd. But what I’ve seen is that folks who haven’t been necessarily brought into the space or go to the space regularly enough, they don’t know how to be a spectator right? So, they don’t know how to clap to the particular beat. They don’t know when they’re supposed to be queued in to actually, you know, help somebody win by providing that energy. The spectators, they’re incredibly important to helping maintain all of the things—from the DJ getting cues from the crowd to know “when should I turn up the music” to also, when is the person going to actually get their 10s? You can kind of tell by the ways that spectators engage with them as well. So, they’re super important to maintaining the structure of the ball.

Eshe: That’s a lot more complicated. Sounds very human.

Dozandri: Yeah. [laughing] Yeah.

Eshe: Do you have another video for me?

Dozandri: Yeah. So I wanted to show you, kind of the embodied reaction that these spectators give you, right? So this is how the crowd really makes do what spectatorship is supposed to look like in Ballroom, right? Where folks in this particular case are going to be walking vogue femme, which is a different kind of category in Ballroom. But it’s one that I think spectators play the most important role in because you not only have to follow the beat, you have to follow the gestures of when folks are performing the dance and respond accordingly. And we’ll see what that really looks like.

[Audio from a video clip of the ball begins]

Dozandri (describing the video): Butch queen versus femme queen: a femme queen in a short skirt, a crop top, sneakers, and a durag while a butch queen is wearing this long, frilly red skirt with no top on, and they’re voguing toward the stage together showing what vogue femme really looks like in the Puerto Rican Ballroom scene.

[Audio from a video clip of the ball ends]

Dozandri: What’d you think?

Eshe: I think that my cardio is not at the adequate level to be competing in this category. So, my hat’s off to these fine contenders. Very high energy. Lots of flexibility, very dramatic. But yeah, you could definitely tell this was the culmination, right? This very much looks like a showdown. I definitely noticed the judging panel, you know, very excited, and you can hear, I guess it’s the DJ, on the mic who’s also sort of encouraging people with their voice as well. So, it really felt very electric and alive, and like everyone is involved, right? Whether you’re, you know, on the runway, whether you’re on the judging panel, or whether you’re a spectator at this point, everyone’s all in.

Dozandri: Yeah, this is where the full kind of metaphor of the circle in Afro diasporic performance comes the realist kind of way alive, I think in the ball, right, where everyone has to kind of coalesce around this space where these two people are voguing, and everyone has to play into that circle, right? So, the spectators, what they’re doing with both the beat and how people are dancing is, there are five elements to vogue performance or vogue femme performance. There’s catwalks, duckwalks, spins and dips, hands performance, and floor performance. And I’m glad you brought up dramatics because there’s a style of vogue that is called dramatics because of that particular explosive performance of the style.

Eshe: Yeah, I saw that sort of like crowd ripple. Yeah, it just sort of ties together what you’ve been saying around this sort of seeming call and response around this circle. People offering up their energy and their support to, you know, these people who are putting so much effort into this like really frenetic performance. Whew! OK, well, I have not moved an inch, but I am quite revved up. Is this it? Is this the culmination? Have we made it to the end of the ball?

Dozandri: We made it. We made it. Yeah. We made it through the ball. We kind of made it through the particular structure of: we go from LSS right to a particular category. We watch folks walk until they win. We learned how to win. And we also learned a little bit about how we’re supposed to engage when we’re at a ball appropriately. Because I think the biggest thing for me is not opening up research to the Ballroom space in a way where everyone’s invited in, but learning the appropriate kinds of ways of interacting with the ball if you were to attend, right? Because there are expectations of community that are really embedded in how the runway works. And that knowledge of how these particular things happen is built over time, right? I didn’t come into this as a linguist and immediately figure it out. This is two years in the making and still in the making of how I make sense of this dynamic, beautiful performance space.

Eshe: And I want to ask you, what was your favorite moment of the night, and why was it so special to you?

Dozandri: Yeah, I mean, I think what’s super special about this particular ball, so it was called the “Black Is Ponka Kiki Ball.” And it was a ball really dedicated to Black femmes. So ponka in Puerto Rico is a term that has to do with queer femininity broadly, you could be nonbinary and be a ponka, you could be a cis woman and be a ponka. You could be a butch queen or what Ballroom calls a gay man and be a ponka. But it’s about celebrating this kind of gender-nonconforming femininity. But specifically, this ball was designed around celebrating how Black femmes are the center of how ponkas make their cultural expression. So, my most favorite parts of this ball were the fact that it was not just going through the regular categories that we see at different balls in Puerto Rico, but making sure that every category was centered around celebrating Black contributions to the scene and kind of, you know, returning to the Black diasporic origins of what Ballroom is really about and centering that at the, kind of, performance level at who was invited to walk on the floor, who was invited to judge, all of that in the structure of that night.

Eshe: So we’re at the end, not only of the ball, but we’re winding down here our discussion, and I would like to know what’s next for you and your research?

Dozandri: Yeah. I think what’s next for me is that I’m fascinated by Ballroom expanding outside the confines of the United States, right? Puerto Rico has this unique kind of colonial relationship, and there’s definitely influences and resonances there, but also a lot of differences in how it’s walked and performed in Puerto Rico in terms of, you know, how Ballroom has developed. I think, for me, the next thing is really thinking about a transnational ethnography of Ballroom. What I’ve been thinking about is expanding this to other scenes across Latin America to see how they’re also innovating in these categories, and how they talk to each other. So this scene in Puerto Rico has connections to the scene in the Dominican Republic. It’s talking currently a lot to the scene in Mexico. And I’m really interested in the scene in Cali, Colombia, where there’s going to be different pricing if you’re not a Black femme entering the space, and some categories aren’t for you if you’re a mestize person or a white person in the space.

And I think that reckoning around how we approach race in this performance floor around a genre that really comes from Black femme legacies is something that’s happening in Latin America in a way that it’s not quite happening the same in the United States. And I think I’d like to look at that transnationally next.

Eshe: Dozandri Mendoza, thank you so much for speaking with me.

Dozandri: Thank you for having me.

Eshe: Dozandri Mendoza is a doctoral candidate at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Their work is based in San Juan, Puerto Rico, and tracks how the growing Ballroom scene there honors their transcestors and creates space for trans-affirming joy.

SAPIENS is hosted by me, Eshe Lewis. The show is a Written In Air production. Dennis Funk is our program teacher and editor. Mixing and sound design are provided by Dennis Funk and Rebecca Nolan. Christine Weeber is our copy editor. Our executive producers are Dennis Funk and Chip Colwell. This episode is part of the SAPIENS Public Scholars Training Fellowship program, which provides in-depth training for anthropologists in the craft of science communication and public scholarship, and is funded by the John Templeton Foundation.