What Is Freedom in a Brazilian Favela?

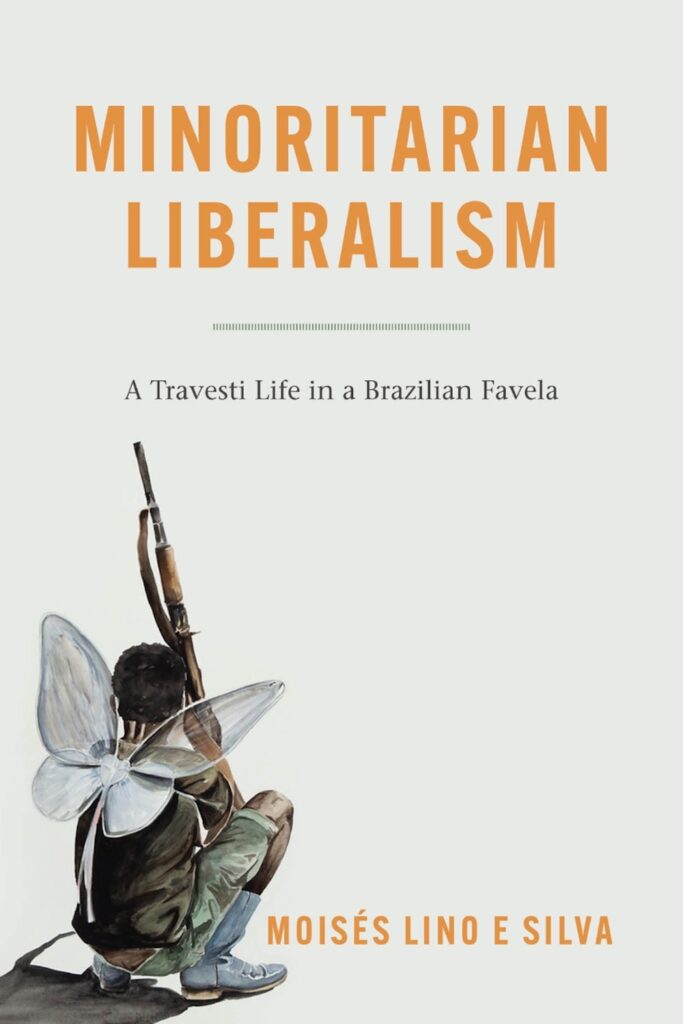

Excerpted from Minoritarian Liberalism: A Travesti Life in a Brazilian Favela. University of Chicago Press, 2022. All rights reserved.

Natasha Kellem liked to talk to strangers. At random, she would approach people in the street and start a conversation. Her preference was for men. That’s how our friendship started way back in 2009. At the time, I was 28 and living in Favela da Rocinha, one of the largest slums in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, to conduct ethnographic research. I was standing outside a corner store in the favela, biting into a juicy piece of watermelon on an oppressively hot day in the favela, when a slow whisper came from behind me, “Delicious!”

I turned around. The voice was coming from a mouth thickly covered in rouge lipstick. I noticed that she was looking at my lips, too, cool and moist from the fruit I was eating. I smiled at her, and she looked down, as if she wanted a bite of my watermelon.

I noticed that she was very thin and quite tall. She was wearing a black tank top, revealing a sculpted abdomen, a pastel pink skirt showing her smooth legs, and high heels, even during the daytime. She had a narrow face with an elongated chin, and pointy ears sticking out through shoulder-length hair. As I followed her enormous dark eyes, she looked up again. Finally, she introduced herself with a mischievous smile as Natasha. I could not resist and surrendered with a broader grin. I was mesmerized by the game.

I had never met anyone quite like Natasha. We soon became close friends.

“Eu adoro dar um it!” (I love to give an it!), Natasha would often tell me, laughing.

It took me a while to understand what she meant by the expression “to give an it.” Another friend of mine in the favela volunteered to explain. “To ‘give an it’ is to take liberties with other people,” he told me. “In this case, to give actually means to take. You take the necessary freedom to do something you want to do.”

I inattentively wrote about the situation in my field notes. I did not realize at that moment how intricate the topic of “liberties” would prove to be in the favela. I scribbled: “Natasha likes to go around chatting and blowing kisses at men. She is ‘giving an it.’ She derives freedom from situations in which I imagined she had none, given all the oppression, prejudice, and challenges she faces as a travesti living in the slum.”

The term travesti is difficult to translate. A couple of decades ago, the anthropologist Don Kulick translated it roughly as “Brazilian transgendered prostitutes.” However, not all who identify as travestis are sex workers. According to the Brazilian National Association of Travestis and Transsexuals, travestis can be defined as “people who live a female gender construction opposite to the sex assigned at birth, along with a permanent female physical construction, and who identify in social, familial, cultural, and interpersonal life through such an identity” (author’s translation). Travesti as an identity thus shares common ground with “transgender” (transgênero in Portuguese), but it historically precedes the latter in the Brazilian context and maintains stronger connotations of deviance and marginality—aspects my friend embraced.

Natasha was very outspoken. She would affirm in a loud and deep voice: “I am a travesti. So what?” Rarely did Natasha use the term transgender; she much preferred travesti. She also denied being a professional prostitute. “I have quit prostitution, love! It’s been a couple of years away from that life!” In 2009, she worked as a cleaning lady in a madam’s home in the wealthy area of Copacabana.

“The old woman loves me!” she boasted.

When I started my research in Rocinha, I had minimal knowledge of daily life in favelas. I believe the same would be true for most middle-class Brazilians like myself. I had never lived in Rio, either. My previous experiences with favelas had been mainly through the media, either watching the news or depictions through movies such as City of God, which uses documentary-style language to portray extreme violence as the “real” face of favelas.

During my years studying anthropology, I brought some nuance to this knowledge through readings on social justice, development, liberalism, and other important themes in urban studies. However, nothing quite prepared me for the situations I experienced when I moved to Favela da Rocinha.

Natasha would affirm in a loud and deep voice: “I am a travesti. So what?”

While living in the favela, I had initially expected to witness oppression everywhere—and to document it using ethnographic methods of participant-observation and interviews. I had assumed that the scarcity of freedom in the lives of the Brazilian urban poor would be an important topic for in-depth anthropological analysis. Above all, I had hoped that an exposé on the lack of liberties in Brazilian favelas could help bring change to the unfortunate situation I anticipated to encounter.

However, it only took me a couple of weeks of fieldwork to start noticing that there was no scarcity of freedoms in the favela in an absolute sense. Instead, day after day, I began to notice different expressions and practices of freedom among Rocinha’s residents.

The problem seemed to be that most of these favela freedoms were not the same freedoms I already knew and that liberal supporters cherished. Some of them were unfamiliar to me and probably unfamiliar to others who had never set foot in a favela. Contrary to what I had anticipated, the research process for what eventually became my book, Minoritarian Liberalism, allowed me to witness liberties where I least expected them to exist and to understand their importance for those who lived by them.

The word liberalism derives from the Latin liber, with a deep history that can be traced back to the Greco-Roman empires. The normative definition of liberalism evoked in my book springs from events in European history, such as the Glorious Revolution (1688), the French Revolution (1789), and ideas derived from European “contractualist” philosophy. Contractualism refers to the argument that some sort of social contract—or a set of laws and shared norms—is necessary for achieving human rights and liberty. [1] [1] Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau are among the most well-known contractualists from the Enlightenment—although they disagreed tremendously over the ideal model of government and how much power a sovereign should have.

The core argument of Eurocentric liberalism is that individual liberties should be protected against abuses of a sovereign ruler, who should have enough power to avoid the potential chaos inherent to the “state of nature” (“the war of all against all,” as British political philosopher Hobbes put it) but not enough power to become a tyrant.

Read more about the roots of liberalism as a political philosophy: “Do Things Have to Be This Way?”

In normative liberalism, “society” should be organized to protect core values such as private property and individual autonomy. Formerly a European project, normative liberalism can now be found in most territories around the globe. It has aligned itself with both left and right political currents, and over the centuries, it has contributed to projects such as colonialism and slavery. Nowadays, liberalism finds its highest expression in the United States, where it is a fundamental value of the Constitution.

Minorities are not excluded from the liberal project in an absolute sense. Liberalism, in fact, presupposes the existence of the “unfree.” Historian Tyler Stovall, for instance, shows how liberty as an idea has been a privilege of Whiteness in nations such as France and the United States—one that depends fundamentally on the unfreedom of racialized others.

In practice, normative liberalism in Brazil has promoted the freedom of privileged subjects, those entitled to “rights” (usually White, heteronormative, and wealthy adults), at the expense of minorities (such as children, travestis and other queer folks, Amerindians, Black people, and favela dwellers). In short, liberalism, for the wealthy, has meant guaranteeing safety from the violence and harms that those in the favelas face daily.

A typical response to these inequalities has been to campaign for the “inclusion” of minorities into liberalism—in other words, the universalization of Eurocentric liberties. But my research with marginalized favela dwellers presents a challenge to this idea.

As Natasha and others showed me, subjects historically marginalized in normative liberalism also respond to their dislocated condition to demand their own versions of liberation. One way they do so is through a process that queer theorist José Esteban Muñoz calls “disidentification,” creative strategies through which outsider populations engage with dominant forces to produce their own truths.

For Natasha and her friends, life in the favela also meant freedom. Not freedom from violence or poverty, as those were daily realities for her and other favela dwellers—but freedom to act out queer sexual desires, to express more fluid identities, to take drugs, to test the limits of their bodies, and to otherwise be themselves.

This is what a queer anthropology of liberalism can offer: an attempt to decolonize liberalism, opening the way for a more expansive politics of liberation.

I still keep a picture of Natasha taken in 2010. Seven people—four women and three men—pose in front of a black-and-white tiled wall, like pieces in a game of chess. We were at the Bar & Mar, a decaying nightclub in the West Zone of Rio de Janeiro, and no one knew exactly how the night would end. Who would fuck whom? Who would kiss whom? Who would pay whom?

In her black, pointy high heels, Natasha is the tallest one in the photo. Her strapless, metallic dress is glued to her slender body, giving her a golden glow. She has no breasts, but she looks very feminine, with smooth hair and delicately applied makeup. Her black, smoky eyes draw attention. In her right hand, she holds a glass of whiskey.

Natasha didn’t like to drink, but that night, she’d made an exception. She’d accepted an invitation to share a fancy bottle of Johnnie Walker Red Label with the young, muscular man standing behind her in the photograph. He wears a tight white T-shirt and blue jeans with white shoes. His bulging biceps wrap around her waist, and his knee peeks out from in between her legs. Natasha responds with a slight smile. She’s enjoying the manly arms wrapped around her.

Those were glorious times for us.

This excerpt has been edited for style, length, and clarity.