Sounding the Border

In the house once occupied by soldiers

laughter echoes

as three women sing

Yamberzal sutures a song

Banafsha, her daughter, gathers a distich

and urges her aunt, Sombul, to carry it on

[1]

[1]

Names of the interlocutors have been changed to respect their anonymity.

Outside, dark enfolds the mountains

thousands of stars gather in clandestine assemblages

a brook gushes inconsolably

bright yellow flowers

murmur spring’s arrival to the insurrectionary night wind

Sombul looks across the gently rising ridges

to the south, she tells me, is the lake cradling tempests

she points toward the military camp overlooking

their home, fields, apple trees

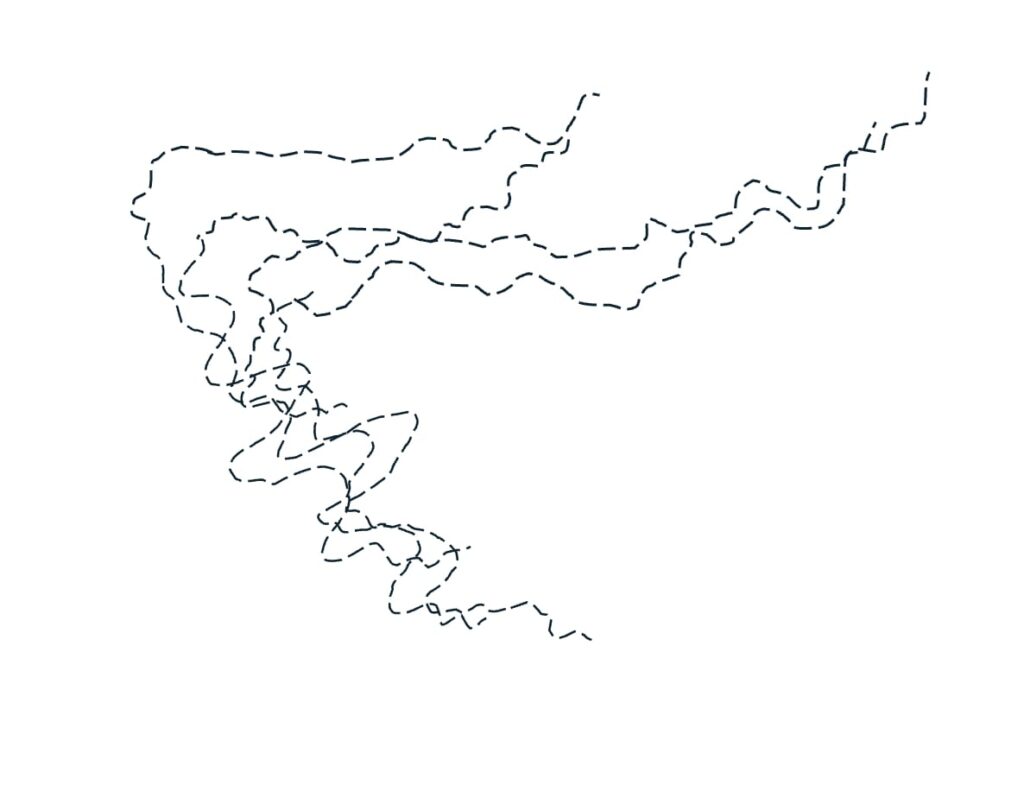

The Line of Control

traces a haphazard arc

far along the hamlet’s northern edge

toward west, it gapes like an open bracket

On a map, the Line exists as a dotted strip

a 740-km “open wound”

[2]

[2]

I borrowed this phrase from Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza.

sundering

meadows and mountains

rivers and songs

Banafsha fetches her mother’s “sound box”

as she turns it on

voices of a wedding troupe

abruptly lash against the room

“From your wedding fabrics

we stitched a shroud

your blood-soaked garment—

who shall wash it, alas!”

Banafsha was a year and a half, she tells me,

when her father was killed—

“My father’s house was burnt down.

This house belongs to my maternal grandfather,

for three years this was an army camp”

Laughter turns to dust,

night passes in an unknown but palpable fear,

and grief spreads through the house

like a low hum

swelling in the dark

resonant through its every crevice

As dawn crawls in through door slits,

we gather again lugging the night in our hearts

snowy mountains and ridges

awash in mist

grappling with light

In her checkered pheran and turquoise scarf,

Sombul sits by the hearth

watching dying embers

The floral rug

—pallid

its blue hues stolen by time

Yamberzal reaches for her medicines

on the sill behind her bed,

a fall in the meadows

while gathering herbs has left her broken, she says,

as she enumerates the healing plants found in the nearby forests:

hand, tripater, sheel hakh, koth, kahzaban

Two friends stop by,

Banafsha initiates the recall of songs

amid rounds of tea and freshly baked bread

women gather fragments,

holding each other

along memory’s ruthless terrain

In the house—

once occupied by soldiers,

voices soar

with refrains

of the ungrievable dead

geographies of loss resound

place after place

a roll call of the dead

refrain after refrain—

those who died near the border

[3]

[3]

The Line of Control is a de facto border between India and Pakistan, even though not an internationally recognized “border” between Indian and Pakistan. The use of the word “border” by my interlocutors—embedded in Kashmir’s everyday political lexicon—is an index of conditions of intense militarization and increasing securitization and surveillance.

those who crossed never to return:

Rasheed, Nabb’e Kak, Javaid, Manzoor, Zahoor,

Gulzar, Rahman, Bayt’e, Magg’e Maam, Latif, Sadaam …

“Rasheed was my paternal cousin,” Banafsha interjects—

“Manzoor was my nephew. Sadaam was also from here,” Sombul says—

“If we sing the names of all those we have lost,

night will descend and our song shall remain incomplete”

In each of their songs,

I listen to time’s severance

—an almostness

“These songs shall journey far away—across times,” Yamberzal

murmurs, pointing toward my recorder

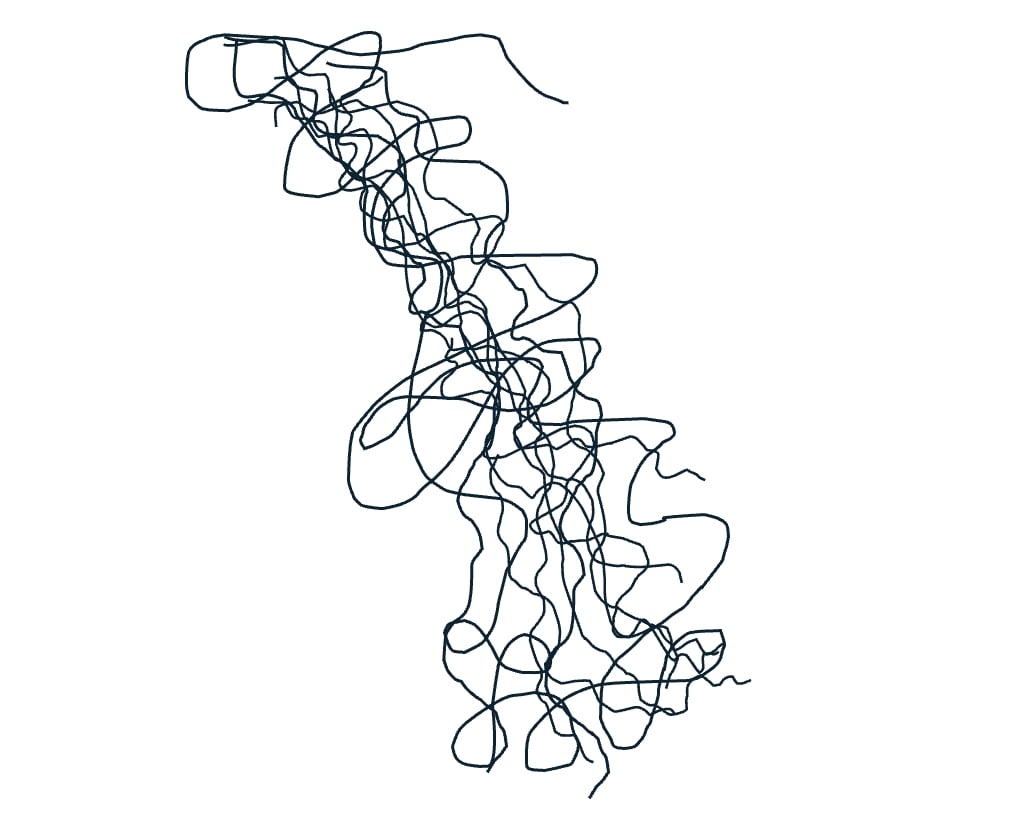

To sound the border is to sound ongoing colonialisms

to sound the border is to sound cartography as empire’s theater

to sound the land broken

choked with shrapnel and landmines

sundered by military camps, watchtowers, concertina

corpses scattered across breathtaking landscapes

to sound the border is to sound the debris of war

to sound the border is to sound severance

belonging and dispossession

a multitude of lifeforms

deathworlds

to sound the border is to sound mortar shells striking against the mountains

cattle crossing over the Line

donkeys blown to smithereens as they stray into landmines

to sound the border is to bury your books, diaries, and photographs

to gather bones and clothes

to sing in a room of broken panes and acrid tear gas smoke—

Who fettered the border in razor wire?

At your abode I wait

to sound the border is to sound waiting

to dwell in suspension

to sound the border is to sound its incompleteness

to sound the border is to sound fugitivity and liberation

to sound the border is to sing it as zulm ki lakeer

[4]

[4]

This phrase, which literally translates to “line of oppression,” is from a song I recorded in Kashmir’s Lolab in 2013.

to sound the border is to sound thousands of sutures

to sound the border is to sound the in-between and the nowhere

impassibility and return

to sound the border is to cross over and over—

not as aberrations or violations

but as ordinary meanderings and wayfindings

to sound the border is to listen to sound trespassing—

azaan drifting across

[5]

[5]

Azaan (also adhan) is the Islamic call to prayer. Calling believers to worship, it announces the five obligatory daily prayers. Recited in Arabic, it is delivered by the muezzin from the mosque.

sound leaking

to sound the border is to listen to

laughter echoing

in the house

once occupied by soldiers