The Politics of Mourning After Itaewon

IN JANUARY 2023, I (co-author Jiho Cha) stood at a podium under cold, harsh lights in the hearing room of the National Assembly in Seoul, Korea, looking out at the audience. Lawmakers leafed through documents in silence, their expressions unreadable. Bereaved families sat with tightly clasped hands and firmly pressed lips while journalists stood behind their tripods, documenting the somber atmosphere.

I paused to catch my breath before facing the gallery and speaking. “The ones who should be sitting here are the bereaved families,” I said, referring to their exclusion from decision-making and official acknowledgment. I held my voice steady, but it was heavy with emotion. The room, already tense, fell into a breathless silence.

As a disaster governance expert, I was designated to testify on the Itaewon tragedy: The night of October 29, 2022, a massive crowd surged at a Halloween celebration in Seoul’s Itaewon district. This led to the deaths of 159 people, including 26 foreign nationals. These hearings, which began in December 2022 and continued with public sessions into January 2023, investigated failures in disaster prevention, emergency response, and accountability.

What began as a typical night of festivities turned into an unthinkable tragedy that Koreans are still trying to process and mourn today.

As medical anthropologists working in Korea, we (co-authors Yeon Jung Yu, Jiho Cha, and Young Su Park) experienced the collective shock and grief that followed. Drawing from long-term research on disaster response and public health governance, and working alongside bereaved families and civic actors, the three of us have studied the Itaewon tragedy to reassess the politics of mourning, normalization of ongoing disasters, and systemic obstacles to real change.

FAILURE TO RESPOND

The Itaewon neighborhood has long been a place where Seoul’s youth, queer communities, and international visitors have gathered, often wandering its narrow alleyways that wind between nightclubs, fusion eateries, and vintage shops. On the night of the tragedy, tens of thousands of people had flocked to Itaewon for Korea’s first post-pandemic Halloween celebration. Before long, the festive mood turned to horror as crowds grew denser in a cramped, sloping alleyway near Itaewon Station Exit 1.

For more than three hours, people called emergency services, warning of danger. Yet the emergency response was delayed and disorganized. When help finally arrived, it was too late: More than a hundred people had died, and civilians were performing CPR in the streets.

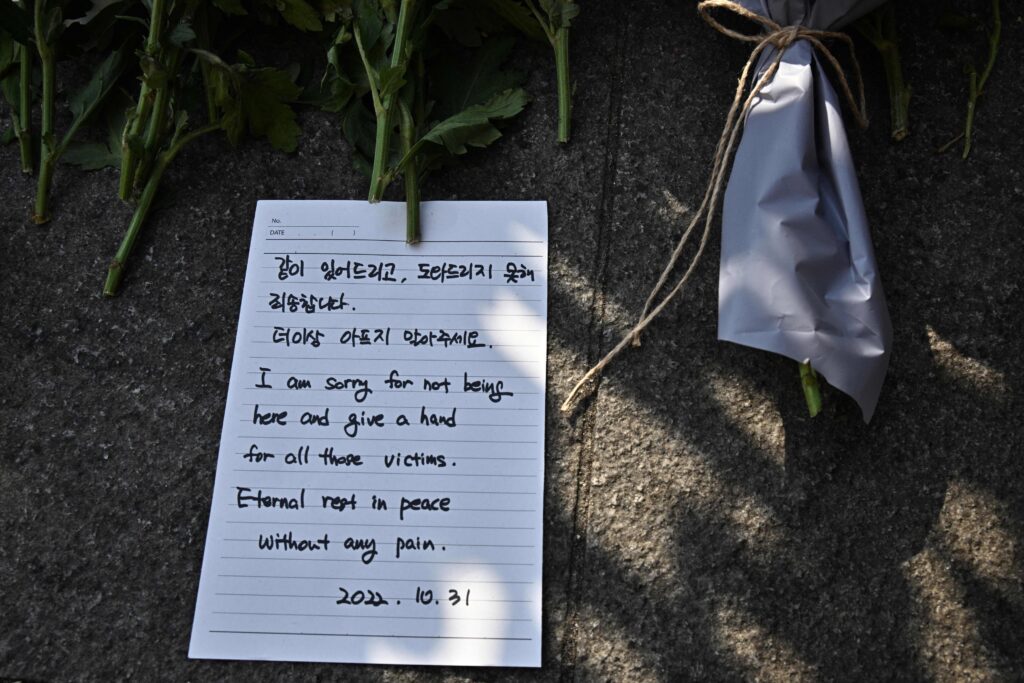

In the days that followed, white chrysanthemums blanketed subway entrances, handwritten notes fluttered in the wind, and strangers gathered in silence. Makeshift memorials sprang up across Seoul in fragile spaces where grief took form. Religious groups held vigils, and community members stood in candlelit solidarity.

The government immediately declared a national mourning period of one week. However, many felt the response was hollow, late, fragmented, and devoid of empathy. Officials vowed reforms to crowd management and emergency protocols, but public trust had already ruptured; warnings from bystanders hours before the crush had gone unanswered. No one seemed to take responsibility.

During the parliamentary hearings, bereaved families were invited to share brief testimonials, albeit as nonparticipating observers. They were not granted the right to question witnesses, no microphones were provided for direct engagement, and no seats were reserved for their voices at the table. They sat in the gallery, listening quietly as experts and officials debated the causes and responsibilities of the disaster that had shattered their lives.

Their grief filled the room—but not the official record. It was acknowledged yet kept at a distance. I (Cha) served as a key member of the parliamentary investigation. During the January 2023 hearings, I said: “The families were there. But the system did not see them. We failed to institutionalize a place for their voices in shaping the investigation and reforms.”

I tried to capture a deeper institutional failure, not only in crowd control or emergency response, but in the democratic process of grieving together.

In the aftermath, the government implemented reforms, including a revised crowd safety manual, expanded disaster simulations, and new laws that clarified interagency responsibilities. Despite these visible measures, the state’s response remained largely technocratic, focusing on risk management and procedural adjustments rather than addressing moral accountability.

“This is not a problem that can be solved by procedural manuals alone,” I stated during the National Assembly hearing. “What’s needed is a people-centered response that acknowledges emotional and moral responsibility.”

When grief could have reshaped policy and public culture, it was instead handled bureaucratically until it disappeared from view.

WHICH DEATHS ARE WORTHY OF MOURNING?

Following the Itaewon tragedy, politicians, commentators, and social media disproportionately blamed the young people, mostly in their 20s and 30s, who died in Itaewon for their deaths, accusing them of seeking pleasure and daring to gather. Some dismissed the tragedy as the result of “reckless partying” or framed the event as a cultural import gone wrong.

As researchers, we observed how both formal and informal hierarchies shaped mourning. State-sponsored mourning rituals were minimal, and although the government declared a short national mourning period in late October 2022, it declined to establish an official recurring national day of mourning.

While some local districts and universities held commemorations, the national response was fragmented. Parliamentary hearings took place, but proposals for an independent inquiry stalled, and online hashtags like #RememberItaewon briefly amplified grief before fading. These moments revealed how mourning in Korea is mediated both formally and informally—through rituals not established, laws not passed, and voices kept at the margins.

Media outlets emphasized the youthfulness of many of the victims but often omitted their names and stories, reducing them to numbers. There was no official memorial site. Discussions about responsibility quickly gave way to debates over crowd behavior. In this vacuum, grief became contested terrain that was expressed privately, politicized publicly, and ultimately, unequally recognized.

We noticed how the Itaewon disaster unfolded differently from the Sewol ferry tragedy of 2014, when over 300 people, primarily high school students on a school trip, drowned off Korea’s southern coast. The tragedy, occurring offshore and involving children under institutional care, pierced the national consciousness and galvanized a nationwide reckoning, as the public demanded answers, reforms, and memorialization.

By contrast, Itaewon is a central part of everyday city life. The crowd surge occurred on a sloping alley lined with bars and clubs, clearly visible to passersby and security cameras. The tragedy unfolded in real time in full public view. The familiarity of the setting made the loss feel more intimate. Yet life quickly returned to “normal” in the days that followed. The alleyways reopened. Cafés filled with customers again. Halloween decorations quietly disappeared.

In the halls of power, an implicit hierarchy of mourning emerged where some deaths were recognized through official gestures while others were sidelined or allowed to fade from public view. These limited official responses, from the short mourning period to the lack of lasting memorials, were calculated to, by design, make the public forget.

This selective memorialization exposes how grief is unevenly distributed, governed by whose lives are seen as legitimate and whose deaths are considered an inconvenience. French philosopher Michel Foucault referred to this as biopolitics: the quiet management of life and death, where institutions decide whose pain is worth acknowledging and whose is not. The Itaewon tragedy laid bare how grief, like everything else, is distributed along lines of power to be managed, categorized, and often ignored. Mourning is not just an emotional experience. It is political.

As I (Cha) noted during the hearings, this form of public judgment became a second blow to the families: “They were not only grieving—they had to justify their grief.”

In a society where moral assumptions condition mourning, some deaths are quietly deemed unworthy of collective sorrow.

AFTER ITAEWON: WHAT MUST WE REMEMBER?

Why do people open their hearts to some deaths and turn away from others? Why do people normalize suffering as part of everyday background noise?

South Korea is a country shaped by the rapid layering of industrialization, democratization, and globalization. Over just a few decades, high-stakes competition and cultural expectations of restraint have pushed grief into the private sphere while the state trends toward mourning in procedural rather than collective ways.

The Itaewon hearings, with victims’ families present in the room, marked a significant change from previous practice in terms of governing. Still, efforts to create an independent investigative body stalled, leaving bereaved families without a strong institutional voice.

Predictably, the hearings closed without a binding resolution. However, February 2023 saw the National Assembly Interior and Safety Minister Lee Sang-min impeached for negligence in disaster planning and response after the Itaewon tragedy, showing that civic pressure could no longer be ignored, though the Constitutional Court overturned the decision that July.

Several senior police officials, including the Yongsan district police chief, were dismissed or indicted, while the Seoul metropolitan police chief was later acquitted. No lawmakers faced direct consequences. Despite televised hearings, public vigils, and expert testimony, systemic reforms to Korea’s disaster response infrastructure have stalled.

Today South Korea faces a political crossroads.

In December 2024, President Yoon Suk-yeol was impeached over his brief martial law decree; in April 2025, the Constitutional Court removed him from office. Many viewed the move as an authoritarian overreach aimed at consolidating power amid declining public trust. While the Itaewon disaster was not the immediate cause, it marked an early turning point in growing disillusionment with the government’s failure to protect its citizens.

This moment of political rupture marks a profound shift in the nation’s direction. It requires significant reflection on how the state addresses death in public life. Who is considered deserving of protection? Whose voices are allowed to influence memory? When the next disaster occurs, who will society choose to remember—or quietly forget? If mourning is to have any meaning, it must prompt action.

Governments can no longer view disasters as unpredictable misfortunes. Recent wildfires, aviation accidents, and other calamities across South Korea reflect the global trend that disasters are no longer exceptional. In this precarious era, leaders must reevaluate relationships with vulnerability, grief, and one another. The government must go further by adopting a new social contract of care that focuses on prevention, guarantees quick responses, and provides long-term support for those left behind.

Our futures depend on it.

In the face of repression and fatigue, Itaewon’s bereaved families have become stewards of memory, carrying forward the unfinished work of accountability through demands for independent investigations, new legislation, and public memorials.

As one father said on the first anniversary of the Itaewon disaster, “Nothing has changed. … The same disasters happen again and again in Korea.” At a memorial altar, a bereaved mother echoed this pain. “It hurts my heart,” she said. “We need a thorough investigation and preventive measures so that young people are never sacrificed like this.”

Remembering is a political act. Honoring the dead means fighting for the living. What we owe is not just remembrance, but a responsibility to a future in which such silence is no longer accepted.