The Power of Mistrust

DEDI WAS HOPEFUL when he joined Indonesia’s leading on-demand platform Gojek as an independent driver in 2015. [1] [1] Names of interlocutors have been changed to protect people’s privacy. The public had lost trust in traditional motorbike taxi drivers. With no standard fees or regulations, passengers felt at the mercy of these drivers, who were often seen as unreliable and dishonest.

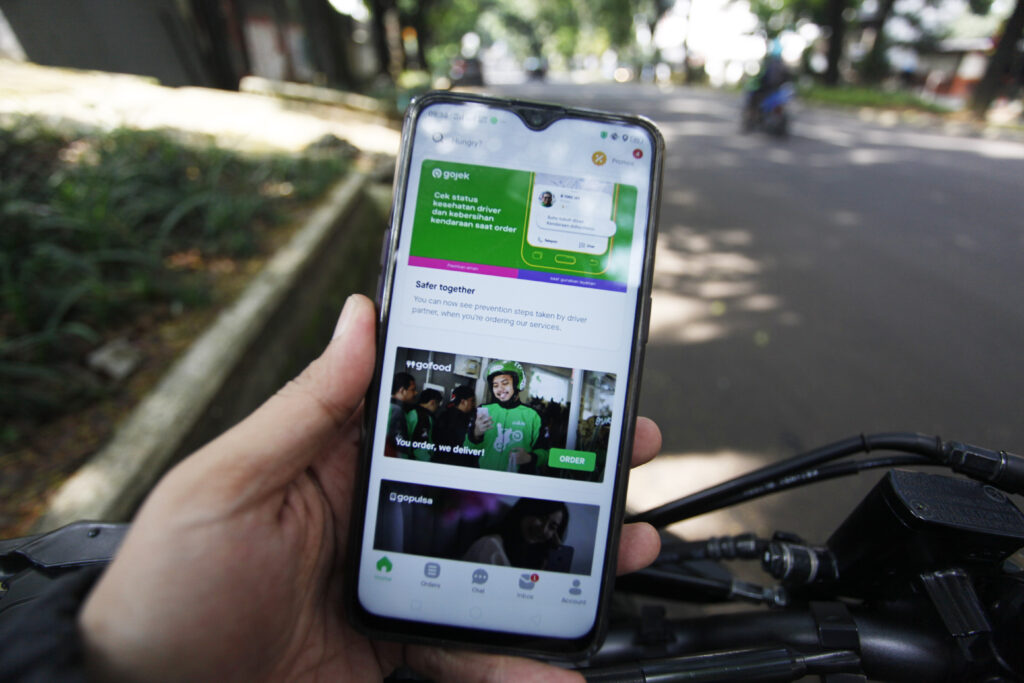

Multiservice on-demand platform companies like Gojek and Grab promised to make commuter transport more efficient across the notoriously gridlocked roads of Indonesia’s major cities. The promise relied on new GPS mapping and financial transaction interfaces that would instill more trust into relationships between drivers, passengers, and the companies.

But over time, the confidence of drivers began to wane as their work became increasingly inflexible. Dedi and members of the Gojek drivers’ association sought to share resources and advocate for drivers. The group often staged peaceful demonstrations outside the Gojek branch office over issues ranging from grievances about pay, working conditions, and over-recruitment of new drivers to demands for free parking at restaurant pickup locations.

As anthropologists, we conducted fieldwork in three Indonesian cities between 2021 and 2024 to learn more about drivers’ mistrust toward platform companies, the government, and one another. At first, we saw the entrenched mistrust as a negative, but over time, we also saw it as one way for drivers to assert some power over a much more powerful company.

When we talked with Dedi in 2023, drivers’ associations in major cities in Indonesia had just orchestrated a protest to demand better pay. For Dedi, however, these demonstrations were not about better pay. Instead, he suspected they were being held to appease drivers rather than to pressure the company.

After decades of authoritarianism in Indonesia, mistrust of institutions and fellow citizens remains deep, despite the country’s transition to democracy over the past 25 years. Authoritarian leader Suharto, who served as president from 1967 to 1998, fostered widespread mistrust by using an extensive surveillance system that infiltrated everyday relationships.

After Suharto’s regime collapsed amid violence in 1998, popular leader Abdurrahman Wahid (a.k.a. Gusdur) urged people to approach the new era with trust and confidence. However, nearly three decades later, Indonesians still harbor great concern about the hidden intentions and actions of others in everyday life—especially in politics.

During our research, we started to see how—in today’s post-authoritarian context—mistrust does not always mean a total breakdown of social relationships. In some cases, it also enables a reworking of those relationships.

We found that drivers’ mistrust of companies, passengers, fellow drivers, drivers’ associations, and the government helped them claw back some control over their work.

MISTRUST TOWARD DRIVERS’ ASSOCIATION LEADERSHIP

Around 2015, drivers began to share resources and information with one another, and small, informal communities evolved into drivers’ associations. While most remain informal, some have registered with the government as “social mass organizations” (ORMAS); other organizations were created with the help of companies.

Membership usually requires time and money, which dissuades drivers from joining. Many drivers also are suspicious that these groups do not in fact represent their interests but rather the association leaders who have been “coopted” by companies and local and national governments.

For Dedi, who belonged to multiple driver communities, these suspicions extended beyond the Gojek drivers’ association.

He heard rumors that leaders from the Grab (a Singapore-based company) drivers’ association had been invited by a cepu kantor, or “office spy,” to discuss Grab’s plan to reduce fares. These cepu kantor are known to keep tabs on drivers’ activities. Dedi was suspicious about what they discussed and whether these leaders were advocating for the drivers. Dedi declared during an interview, “The association is now—let’s be honest—standing up for the [Grab] office. When it comes to bribery or getting money, I’m sure they [Grab] are getting it.”

Dedi’s doubts speak to a broader erosion of trust among long-time drivers over whose interests association leaders are supposedly serving. Members typically select their leaders, but over time, mistrust grows as they begin to doubt their sincerity. Tama, another driver we interviewed, described the drivers’ association as a boneka—a puppet serving the interests of the platform company.

At first, we interpreted such mistrust as solely negative because it weakened the solidarity that drivers needed when organizing against the companies for their rights. Over time, however, we saw that it was also a way for drivers to hold onto some of their power instead of giving it all away to leaders who claimed to be working on their behalf. This mistrust gave drivers a healthy skepticism, making them more careful in how they related to the company.

DISTRUST TOWARD GOVERNMENT AND COMPANIES

When on-demand apps were still new in Indonesia, companies offered generous bonuses to attract drivers, enticing them with the promise of earnings that exceeded the regional minimum wage, which ranges between US$60 and US$120 per month in cities like Yogyakarta.

Andi, who started to drive for Gojek in Yogyakarta in 2016, said that during his first few years, he could earn US$30 a day with the generous bonus structure. But today many drivers are, on average, earning a tenth of what they were a decade ago. Bonuses became almost impossible to achieve. Drivers felt compelled to work longer hours, but at the same time, they waited longer between passenger orders as more drivers entered the market.

Many started questioning whether the bonus schemes were meant to support drivers at all.

Lambang, a 33-year-old driver from a small town near Bandung, on the island of Java, described the new bonus system as unreasonable. It was so unrealistic, he said, that no matter how hardworking a driver was, they could no longer achieve the rewards that companies promised to deliver.

Drivers described the app they use to interact with both the company and passengers as opaque, unpredictable, and often changing. For drivers, the app was turning into a tool for exploitation controlled by the company—not them.

When the company did appear on the ground, it was often in the form of a field coordinator or satgas. The company employs satgas—sometimes former drivers themselves—to monitor drivers. Satgas would pretend to be passengers and then reveal themselves at the end of the journey. Drivers consider this practice spying.

This is not the only form of spying the companies do. One driver named Sri explained that another driver offered her a side job as a cepu kantor to report in secret on her fellow drivers. Sri took the job for a while but grew uncomfortable spying on her fellow drivers and quit. The presence of spies made it clear to drivers that their companies did not trust them and that their communities were under constant surveillance.

As early as 2015, drivers’ associations began to organize protests over grievances toward their companies. But more recently, associations have started to appeal directly to the Indonesian government. In August 2023, drivers with the association Forum Ojol Yogyakarta Bersatu took their demands to the government legislative body, calling for the establishment of a regional legal framework that regulates fare structures, delivery rates, and application oversight.

Hadi, a driver with Gojek, was unconvinced.

“The key thing is for the governor to make rules that truly benefit the drivers rather than just bermain [play around] with these platform companies,” Hadi said.

The word bermain is often used to describe backdoor deals or bribes. For Hadi, the government’s apparent passivity hints at complicity, not merely indifference. Driver leaders directly involved in discussions with a company or the government are often seen as involved in such backdoor activities. For the drivers, evidence of this lies in the lack of any significant outcomes or regulatory actions from the protests.

The drivers we interviewed said company workers and government officials appear out of reach, tucked away in their offices and located in other cities, making it nearly impossible for drivers to know who is behind what decisions. Many were adamant that the company and government were untrustworthy, unknowable, unpredictable, and uncontrollable.

DIALOGUE OR DECEPTION

In May 2025, thousands of on-demand motorcycle taxi drivers took to the streets in coordinated protests, demanding fairer treatment from companies that take a larger cut of fares than government regulations allow. The demonstrations ended with few results, leaving drivers increasingly frustrated and distrustful.

That mistrust exploded on August 28 of this year, when nationwide labor protests outside Parliament in Jakarta turned deadly. In the chaos, 21-year-old Affan Kurniawan, a driver finishing a food delivery for an online app, was struck and killed by an armored vehicle belonging to the National Police Mobile Brigade (Brimob). The vehicle didn’t stop. A bystander’s video of Kurniawan being run over spread rapidly online, igniting outrage. For motorbike drivers already struggling to make ends meet, Kurniawan’s death became a symbol of how little their lives seemed to matter. Within days, protests erupted across cities and towns, met in many places with tear gas and police violence.

Trying to calm the fury, Vice President Gibran Rakabuming Raka invited several drivers to a dialogue on August 31. But the move backfired. None of the major motorbike associations recognized the participants, and rumors quickly swirled that the meeting was staged. Tempo newspaper reported that the supposed driver representative spoke in unusually formal, “high” language—so unlike the way most online drivers talk—that many suspected he was planted. His use of the word “cadet” instead of “member” struck drivers as a clear sign of corporate training and loyalty to the apps, not to the community. On social media, narratives spread that the government was meeting with impostors while real drivers were still out on the streets.

Gojek and Maxim (another on-demand app) later confirmed that the invitees were indeed registered drivers chosen by the companies. But by then, the damage was done. The mistrust between drivers, government, and the platforms they rely on had only deepened—and it was clear that no quick dialogue would repair it.

DEPLOYING EMPATHY

Some companies acknowledge mistrust as an issue. The Gojek podcast “Go Figure” aims to provide “unfiltered” and “real” discussion about their company. In episodes, Gojek executives acknowledge that engineers, who rarely meet drivers, often view them as “scammers.” This negative view of drivers mirrors a popular view of the wong cilik, or common people, as dishonest.

Yet these companies tend to reframe conversations about mistrust by preferring more corporate words like “empathy” when talking about tensions between drivers and companies, and the extent to which company leadership should identify with drivers’ problems. As one executive explained, too much empathy with drivers was “reactive empathy” or “far too emotional.” Instead, it was better to have “constructive empathy” that was “more systematic and rational.”

Mistrust—we learned—is a strategy for asserting one’s own agency under tough and often authoritarian conditions.

By deploying corporate language to talk about mistrust, these executives acknowledge and strategize on how to bridge the gap of mistrust in a softer, more palatable way without wanting to overcome it. This approach allows the executives to decide how much trust they want to give the drivers while protecting their profits.

Mistrust can disrupt and harm labor relationships and even generate violent outcomes. But Indonesia’s on-demand economy has taught us that mistrust is more complicated: It allows people in unequal relationships to engage while sometimes mitigating personal risks.

The drivers’ associations have not managed to secure significant wins in drivers’ working conditions. As a result, mistrust continues to pervade the on-demand motorbike industry and is only getting worse. These companies continue to benefit from drivers who mistrust one another and cannot organize effectively to defend their interests. At the same time, drivers continue to approach their work with a healthy skepticism that pushes against company desires, affording them a small amount of much-needed autonomy.

Mistrust—we learned—is a strategy for asserting one’s own agency under tough and often authoritarian conditions.

But more than that, it is in fact the means through which people with conflicting interests can work together amid uncertainty without surrendering too much of themselves in the process. Transparency alone will not solve mistrust—it will persist as long as power and economic justice are denied to those with less.