Who Pays the Price When Cochlear Implants Go Obsolete?

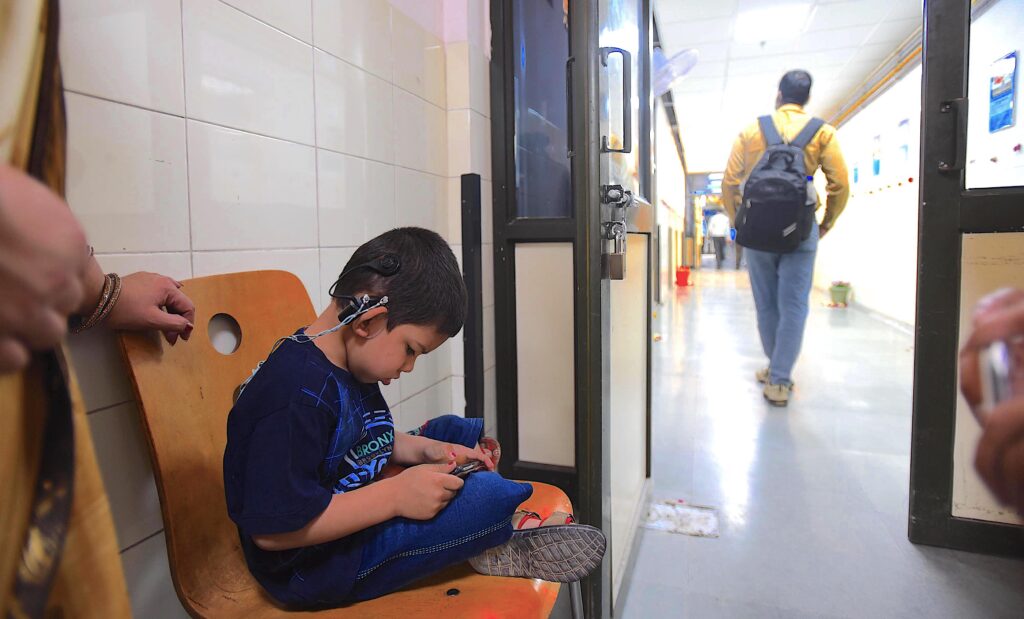

In 2021, my research assistant and I interviewed Nikhil, a father in Delhi, about his family’s experience getting their deaf son Vikas a cochlear implant. [1] [1] All names have been changed to protect people’s identities. Vikas had qualified for an innovative and ambitious central Indian government program that provides the devices to children under the age of 6 whose families live below the poverty line.

Nikhil recalled the nerve-wracking experience of watching his then 4-year-old child undergo surgery. After the implant was activated a few weeks later, Nikhil said he and his wife struggled to ensure Vikas was continually wearing the external processor—the part of the device worn behind the ear that sends signals to the brain to process sound and speech. The parents talked constantly with Vikas to develop his sense of hearing, and they encouraged their other children to do the same.

But the struggles were worth it; the cochlear implant worked. Thanks to the device, Nikhil told us, Vikas was able to attend school. Now, at age 8, he was succeeding at the same grade level as his peers.

However, after four years of using and maintaining the cochlear implant—including the external processor, spare cables, magnets, and other parts—the family started receiving letters and phone calls from the cochlear implant manufacturer headquarters based in Mumbai. Their child’s current processor—a “basic” model designed for the developing market—was becoming “obsolete” and would no longer be serviced by the company. The family would need to purchase another one, said to be a “compulsory upgrade.”

“We worry that all the hard work we have put in will all go to waste when the machine company stops manufacturing the device,” Nikhil told us over the phone. “New machines are so expensive. If we somehow even get another one by gathering money from somewhere, who will give us the guarantee that this will not happen again and again? We are helpless.” Nikhil’s frustration was palpable.

This father and other parents in India with whom I spoke discussed the impossible calculus they were facing. Many were migrants to Indian cities and were daily wage earners with unstable employment. How would they manage to feed their families, pay for school fees and medical care, and afford a new cochlear implant processor for their child?

They wondered why the devices were being made obsolete and what their child’s future would be. These fears were compounded by the fact that the parents had been told by medical experts that getting a cochlear implant was the only option for their child to have a full life. They had not been told about, let alone taught, Indian Sign Language or given other skills to help their children communicate and navigate the world.

Instead, they had become dependent on a single medical device—and by extension, on an entire multinational corporate system whose financial goals seem to contradict companies’ aims to support clients’ hearing over their lifetimes.

ACCESSING COCHLEAR IMPLANTS

There are at least 1 million cochlear implant users throughout the world. I’m one of them.

Since their commercial introduction in the 1980s, cochlear implants have come to be considered both the gold standard in intervening on hearing loss and the most successful neuroprosthetic device. Though cochlear implants are not always successful, when they do work, they often work well and are integrated into a person’s sensorium. That’s why governments around the world, including India’s, are funding cochlear implant surgeries.

Thanks to my U.S. health insurance, when my external processors were rendered obsolete, I was able to receive free-of-cost compulsory upgrades. But that’s not the case for everyone. Devices are made obsolete at different times in different places, and people around the world face unequal access to these technologies, depending on their finances, health insurance, and health care systems. Cochlear implants cannot be tinkered with or repaired outside of the official cochlear implant corporation facilities, making people completely dependent on the device makers.

We need a stronger term than “planned obsolescence” to describe the profound sense of loss people feel when cut off from their sensory worlds.

In my new book, Sensory Futures, I write about cochlear implantation in India and the ways these devices are changing understandings and experiences of deafness more broadly. As a medical anthropologist, I draw from extensive conversations with families, government administrators, surgeons, and audiologists throughout India. The book explores how cochlear implants introduce new possibilities and limits for how people sense the world and communicate and relate with one another.

The families with whom I spoke struggled to understand what was happening to them. Why had the Indian government given their children such devices if they could not afford to replace them? And why weren’t cochlear implant corporations, which claim to be committed to cochlear implant users for their lifetimes, maintaining devices for longer periods of time?

THE STRATEGY OF PLANNED OBSOLESCENCE

As the families learned, cochlear implant makers, like many global technology, electronics, and automotive companies, rely on planned obsolescence—a strategy of deliberately phasing out products or parts to create continual consumer demand for new ones.

The term “planned obsolescence” was coined by U.S. real estate agent Bernard London in 1932. London argued that the state should incentivize the production and subsequent purchasing of newer objects and infrastructure to boost the economy during the Great Depression.

But today, the term is used to refer to a wide variety of corporate strategies designed to spur consumption, mostly by individuals. These techniques include continually redesigning products, stopping the supply of spare parts, failing to offer necessary software upgrades, or using materials that quickly degrade.

In the case of cochlear implants, corporations regularly introduce new devices and stop servicing older generations of processors.

Increasingly, consumer activists and other concerned citizens are demanding that users be granted the “right to repair.” Whether it’s a washing machine, a car, or a cellphone, users should be able to fix products that break down instead of being compelled to buy new ones. Right-to-repair activists criticize the profit-driven and environmental costs of planned obsolescence and aim to change these systems through education and legislation.

Still, these important efforts often miss part of the story, especially when it comes to neuroprosthetic devices like cochlear implants that become part of a person. The stakes of obsolescence are very different when the loss of a device means the loss of a sense.

Cochlear implants are not like phones or microwaves or laptop computers. Companies market these devices as “bionic ears,” using slogans such as “Hear for you. Always.” According to the logic used and mobilized by cochlear implant proponents, children who use implants can and do develop hearing brains, or brains attuned to auditory stimuli and to hearing as a way of processing information. In the absence of a device, this way of life is forcibly, and often abruptly, lost.

The same goes for other neuroprosthetic devices, such as the “bionic eyes” developed by the company Second Sight. The retinal implant device, used by people who are blind or who have low vision to simulate sight, was recently declared obsolete by its manufacturer. The users were terrified by the prospect of having to adjust to life without the bionic vision they had to come to rely on to navigate the world.

We need a stronger term than “planned obsolescence” to describe the close relationships people develop with their neuroprosthetic devices and the profound sense of loss they feel when cut off from their sensory worlds. We need a concept that reflects this violence.

I propose “planned abandonment.”

Consider the Oxford English Dictionary’s definition of “abandon”: “To desert or forsake (a place, person, or cause); to leave behind; to leave without help or support.” Abandonment, as opposed to obsolescence, has moral connotations.

ADDRESSING PLANNED ABANDONMENT

What happens when a sense becomes obsolete because of corporate abandonment?

To continue to hear despite device obsolescence, families often turn to the thriving informal economy of Facebook groups and other social networking sites where a busy trade in spare cochlear implant parts exists. Stratified obsolescence, where certain devices become obsolete in one country but not in another, has resulted in a lively and emotional transnational market where parents post poignant messages asking for spare parts and contact relatives and friends living in other countries to see if they can locate parts elsewhere.

I recently realized, for instance, that one of my old cochlear implant processors that was gathering dust in a cabinet could still be serviced in India. Although it’s obsolete in the U.S., the component could mean the difference between a child in Delhi hearing or not.

All the families in India with whom I talked were trying to find ways to finance needed upgrades for their children’s cochlear implants. They were cobbling together loans, seeking extra work, and cutting down on other expenses, often for essential things such as food and school fees.

In one especially devastating case, a father lamented that his daughter, who had been doing well with her implant, could no longer hear since her device had become obsolete. All the gains she had made in listening and speaking had come to a standstill. She could no longer attend school because she could not follow what was being said and was not offered any accommodations. They were at an impasse: unable to afford a new processor and unable to imagine a different future.

As neuroprosthetics become more ubiquitous, individuals should not have to rely on informal marketplaces and the goodwill of strangers to maintain access to these devices. The corporations that manufacture them and the governments that distribute them must also be responsible for maintaining them for the long term.

Until then, instead of planned obsolescence, let’s call it what it is: planned abandonment.