Reclaiming Tanzania’s Deep Past—Together

LAST YEAR IN DAR ES SALAAM, I sat down with archaeologist Fidelis Masao over a cold Coke to talk about our shared archaeological research. Professor Masao, an expert on Tanzania’s ancient history who first taught me how to identify stone artifacts as a student in 2008, chatted with me in a mix of English and Swahili. When his 7-year-old grandson wandered over to our table, Masao gave the curious boy a quick lesson on stone tools.

“Did they use them like swords?” the child asked. Masao chuckled. “People here relied on sharp stone tools for over 2 million years!” he said, letting that sink in before the boy scampered off again.

Masao then turned to the serious reason for our meeting. Tanzania’s precious archaeological record is disappearing, he warned, worn away by erosion and damaged by human activity. Old photographs from the 1950s onward show how much of the record has vanished. We were determined to find a way to help halt this destruction—by working together with the local communities living on these ancient lands.

Tanzanian voices have long been sidelined in research on the country’s deep past. For decades, foreign scientists led digs and published papers on discoveries from places like Oldupai Gorge or Kondoa, while local communities were rarely consulted and Tanzanian scholars received relatively little support. To truly safeguard and understand human origins in this region, we need a new model—one grounded in collaboration, mutual respect, and shared stewardship.

As a U.S. archaeologist and researcher on human origins in Tanzania, I knew I had to rethink my role. Instead of acting as the typical outside expert, I would strive to be a collaborator who empowers and amplifies Tanzanian perspectives.

Kisese II: A Rockshelter and a Community

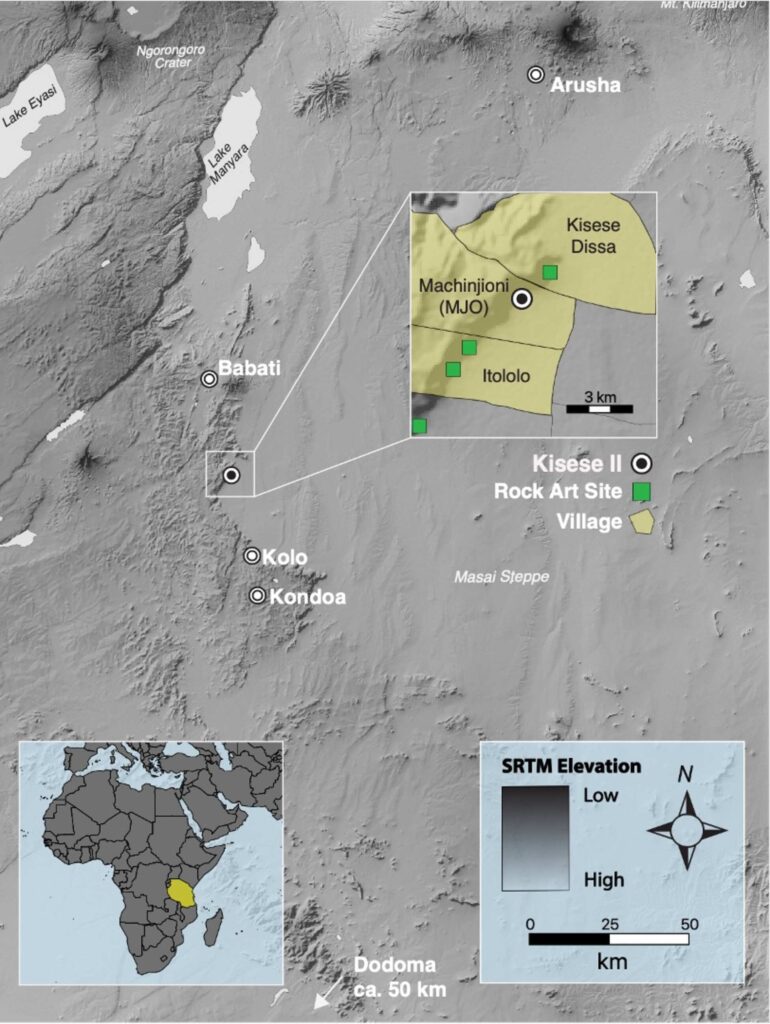

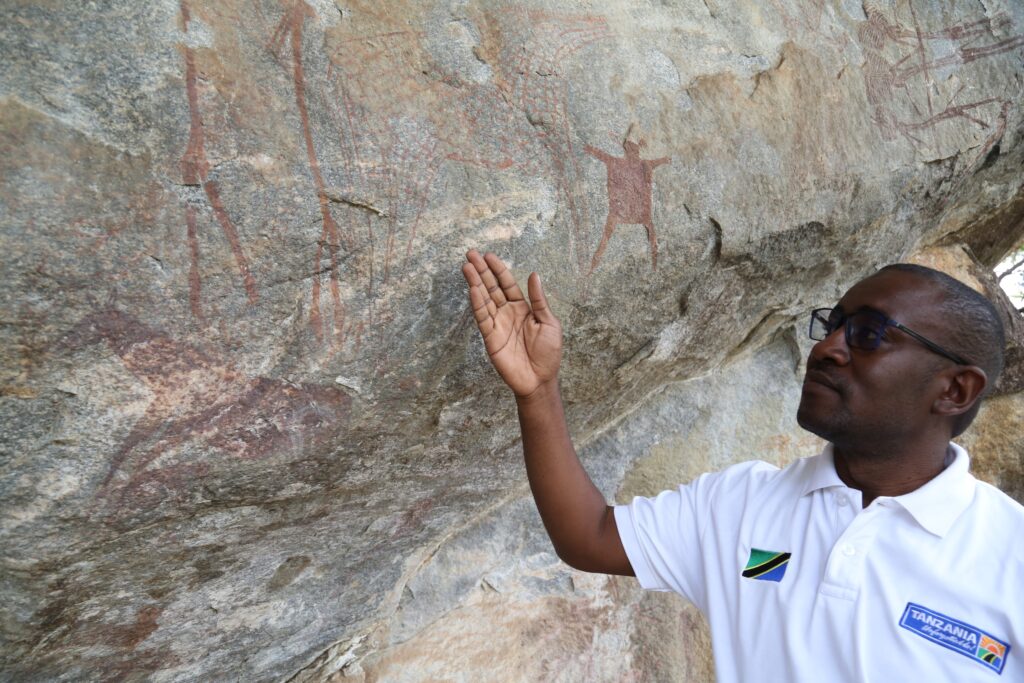

Since 2015, I have focused my efforts on Kisese II, a rockshelter in central Tanzania’s Kondoa district—an area famous for its ancient rock art (now a UNESCO World Heritage site). The shelter is perched among giant boulders above the Masai Steppe, near a small village called Machinjioni. About 150 people live there, farming corn and millet, and herding goats, sheep, and cows. Many villagers are Muslim, with a few Christians, and many also practice ancestral traditions.

To scientists, Kisese II is a trove of Stone Age artifacts and fossils that can illuminate early human life. But to Machinjioni’s people, this rockshelter is part of a living cultural landscape. Before the research started, the village elders held a ritual at the site: They sacrificed a sheep to honor the ancestors believed to dwell in the shelter and to ask those ancestors’ permission for the research. According to the elders, the ancestors gave their blessing.

When it came time to begin fieldwork at Kisese II, I refused to follow the old “parachute paleoanthropology” playbook. In many places, especially countries with colonial histories, “research” is a dirty word—often associated with outsiders exploiting local bodies, lands, and histories. In Tanzania, specifically, research and colonialism were indelibly linked. Decades of German and then British rule fundamentally shaped who studied the past and how. I also understood that archaeological research without local involvement could backfire. For years, stories of German colonial gold have led some villagers to dig at rockshelters like Kisese II in search of treasure, where they’ve accidentally unearthed human skeletons and artifacts in the process.

I turned instead to a community-driven approach, inspired by trailblazers of participatory research, in which community members shape the agenda and contribute to research as equal partners. My training at various archaeological sites around the world, such as Pinnacle Point in South Africa, Abri Pataud in France, and Koobi Fora in Kenya, showed me how human origins research could do more than reshape our understanding of evolution—it could serve the communities living near these sites.

In collaboration with Masao, I was determined to transform human evolution research methods from extractive to generative—one that nourishes relationships, builds capacity, and supports long-term stewardship. Masao had conducted his dissertation research in Kondoa and had worked with Warangi people living there, publishing important insights about stone tool use in ritual ceremonies. Working with him, Tanzanian college students, and heritage officials, I led renewed fieldwork at Kisese II starting in 2017.

We first held village meetings in Swahili to discuss plans, questions, and ideas. A central insight that came from the Machinjioni community involved the need for the research to create community benefit. Through systematic meetings in which both elected officials and residents shared their views, we decided to integrate the research and community benefit by contributing to the building of a primary school, one that the village had already started constructing.

We also used technology in creative ways to bridge gaps. For example, we built a virtual-reality tour of the site so that people who couldn’t hike up to it—especially older villagers—could still explore it. Just as importantly, we made sure information flowed freely. We shared findings with Tanzanian museums and authorities in real time. We set up a WhatsApp group, Slack workspace, and online shared folders so that everyone, from village leaders to students in Dar es Salaam, could follow along with the discoveries. This kind of openness was a stark break from how research with foreign scientists is often done in Tanzania.

Reflections on Power and Privilege

This slower, inclusive way of doing science came with its own challenges. When we launched the Kisese field project in 2017, I was a young scholar fresh out of graduate school and under pressure to “publish or perish.” It might have been easier, career-wise, to stick to the conventional path—dig fast, collect data, and ignore the people living there. Spending time building local partnerships felt riskier, and some colleagues wondered if I was sabotaging my future spending all this time “in meetings.”

During difficult moments, I reflected on why I felt so strongly about sharing power in research. I realized it harked back to my own upbringing. I grew up relatively poor in peri-rural Florida, raised by a single mother, far from any centers of conventional “influence.” Even now, classist and dismissive comments about my upbringing circulate in academic spaces—“at least you don’t have to live in Florida,” one Ivy League colleague stated, and “I would never raise my family in the South,” said another, regarding career opportunities. These comments act as a reminder of the hierarchies that continue to shape who is seen as legitimate and who is considered inferior, even when it comes to writing deep history.

Being a woman with a career, especially in science, comes with different challenges too. In many ways, I know firsthand what it’s like to feel marginalized and voiceless in a field still largely dominated by male voices. This awareness gave me empathy for others who have been excluded. It fueled my conviction that science—especially about something as profoundly human as our origins—should not be a one-sided story told by outsiders.

Over time, I found mentors and ideas that gave me confidence. One framework that resonated was the idea of an “archaeology of the heart”—doing research not just with your head but with empathy and humility, intertwined with scientific rigor. By following my heart at Kisese II, we didn’t just unearth ancient beads and bones; we also built trust, local pride, and a sense of ownership among the people who are the custodians of this history. To me, those human connections are more valuable than scientific discoveries.

A New Way Forward

As my chat with Masao in Dar es Salaam wound down, we finished our Cokes and watched his grandson chase a lizard in the courtyard—a reminder of the next generation who will inherit this history.

Tanzanian research today is changing: More local archaeologists, like Arizona State University student Husna Mashaka Katambo, are earning degrees and leading research teams, though they still face serious challenges, especially a lack of access to sustainable funding, which programs like the The Leakey Foundation and Paleontological Scientific Trust are beginning to improve. In addition, communities like Machinjioni are being treated as true, equal partners in leading research and preserving heritage. Our ongoing work at Kisese II is just one small part of this broader movement toward inclusive, sustainable paleoanthropological research.

In a field long dominated by foreigners, our experience shows that a community-driven approach to paleoanthropology in Tanzania is not only possible, but profoundly beneficial. By sharing power and knowledge, we make research more meaningful and more just. I hope our experience inspires other researchers—whether in Africa or elsewhere—to rethink how they engage with communities. Human origins are part of a story that belongs to everyone, and their study can truly thrive only when we work together as equal stewards of the past.