Six Reasons to Save Archaeology From Funding Cuts

This article was originally published at The Conversation and has been republished under Creative Commons.

Archaeology is in trouble. The U.K. government recently announced plans to cut its subsidy for English university teaching of the subject (along with many arts courses) by 50 percent because it is not part of the government’s “strategic priorities.”

Education Secretary Gavin Williamson framed this in terms of encouraging more students to study subjects in the sciences rather than “dead-end courses that leave young people with nothing but debt,” implying he thought archaeology was among these courses.

If this cut goes ahead, it would significantly impact universities’ ability to teach the subject. Several universities are already considering downsizing or even closing their archaeology departments.

This discounts the immense importance of archaeology to society. Not only does it help us interpret our past but it helps us better understand our present and shape alternative futures. The loss of such work would be devastating.

Here are six reasons why archaeology has never been more relevant to society.

1. Archaeology is not (only) about the past

The perception still lingers of archaeologists detached from reality, stuck in the past, excavating ancient worlds to fill museum stores with newly discovered treasures. This perception is far removed from the reality of archaeology as a progressive and future-oriented discipline, one that uses evidence from the past to explore contemporary and anticipated future challenges, such as climate change.

In Tanzania and Ethiopia, for example, archaeological evidence has revealed that some historical agricultural construction techniques were less effective at stopping soil erosion over the last 500 years than previously thought, while others worked in a different way. These findings have now been used to guide future farming practices in this increasingly arid environment.

2. Archaeology is a science

Archaeology is traditionally positioned within the realm of arts and humanities. This is no longer appropriate since scientists have become more prominent within archaeological research.

Science has been defined as “the pursuit and application of knowledge and understanding of the natural and social world following a systematic methodology based on evidence.” With only minor adjustment, this definition also stands for archaeology. The prominence of science means that archaeology now aligns more with sciences than the arts.

The University of York’s BioArCh facility, for example, runs SeaChanges, which draws upon archaeology, zoology, marine ecology, and conservation biology. It looks at how people have exploited marine vertebrates, with projects covering species from herring to sperm whales to find ways to help biodiversity recover.

3. Archaeology is a universal discipline

Archaeology focuses on understanding how people in the past interacted with the world around them. It explores how their decision-making shaped their world and the impact that had on the future.

To better understand these past worlds, archaeologists work to advance understanding with other subjects in collaborative and interdisciplinary projects. In a recent audit, archaeologists at the University of York were found to work with researchers in almost every other department—from law and music to management and health sciences.

Archaeologists also work increasingly with the public, including initiatives designed to enhance the well-being of participants. An example is Operation Nightingale, which is a military initiative that gives service personnel who have suffered physical injuries or mental illness a chance to get outside and learn new skills as part of their recovery.

4. Archaeology can help shape a better world

I have recently been studying “wicked problems,” those significant global challenges—including social injustice and inequality, environmental pollution, and global warming—the resolution of which will be hard to achieve. Where some resolution is possible, it is likely to include creative, unconventional, and cross-disciplinary solutions.

Examples that illustrate archaeology’s potential to help resolve such wicked problems include my work in Galapagos, where archaeological methods are being used to work out what sources plastic pollution has come from. This can help focus attempts to change people’s polluting behavior and so reduce the impact of waste on an iconic marine environment.

5. Archaeology is important to the economy

Over 7,000 archaeologists are employed in the U.K., according to a recent survey. Thousands more are working around the world, some within universities but far more commonly for agencies, museums, heritage consultancies, and contracting field units that undertake archaeological work in advance of construction.

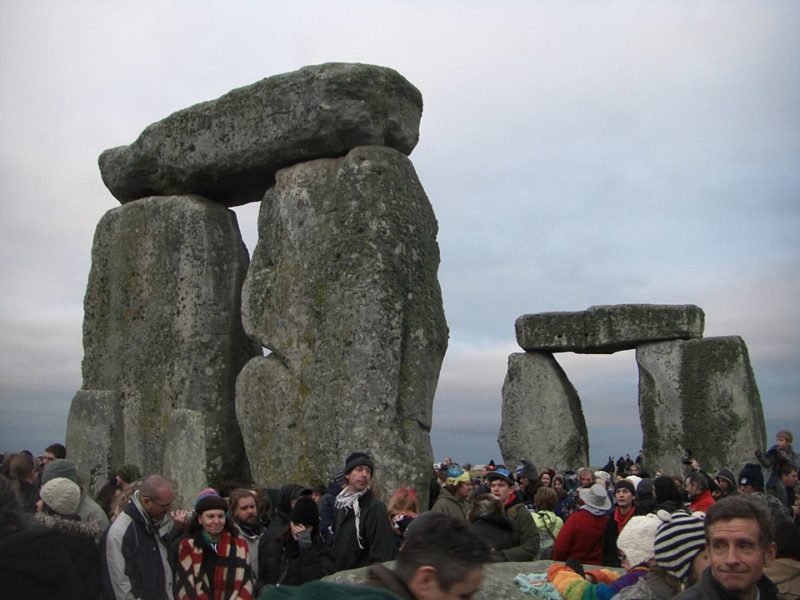

A report assessing the heritage sector in 2019 found that heritage tourism contributed 17 billion pounds (around US$24 billion) to the U.K. economy, much of this driven by or related to archaeology.

6. Archaeology is an excellent foundation for any career

An archaeology degree provides a diverse range of transferable skills. It incorporates sciences and social science alongside more traditional arts-based learning. At the University of York, we have graduates who have successfully followed military, legal, financial, and journalistic careers, as well as the many who did become archaeologists. What all of these people have in common is a deep understanding of humanity. Archaeology is fundamentally about people, and this focus impacts strongly those who study it.

We live in uncertain times. People will feel more secure with the knowledge that human society is resilient. Archaeology is central to providing this knowledge. Now is the time to invest in a discipline that is uniquely placed to help tackle global challenges and shape a more stable future.