The United Fruit Company was a U.S. multinational corporation and at one time, the largest landholder in Central America. To maintain authority in this part of the world, the company stamped out labor reform, collaborated with U.S.-backed coups, and, oddly enough, invested in archaeology. Why?

In this episode, anthropologist Charlotte Williams explores the company’s role in preserving the past. She discusses United Fruit’s botched conservation project at the Maya site of Zaculeu and the ongoing impacts of that program.

Charlotte Williams is a Mellon Democracy and Landscapes Initiative fellow at Dumbarton Oaks, Harvard University (2024–2025), and a Ph.D. candidate in anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania. Her research explores how archaeology as a discipline has been used in U.S. imperial projects, with a focus on how the United Fruit Company used archaeology to grow territorial power in Central America. Charlotte has worked on community museum projects, coordinated decolonizing museum programs, and co-curated an independent art exhibition.

Check out these related resources:

- “The Fruits of Extraction”

- “Zaculeu, Guatemala: reflexiones y propuestas para un retorno local”

- Zaculeu, fortaleza mam Facebook page

- “Conquest and Revival at Chiantla Viejo: The Transition of a Highland Maya Community to Spanish Colonial Rule”

SAPIENS: A Podcast for Everything Human is produced by Written In Air. The executive producers are Dennis Funk and Chip Colwell. This season’s host is Eshe Lewis, who is also the director of the SAPIENS Public Scholars Training Fellowship program. Production and mix support are provided by Rebecca Nolan. Christine Weeber is the copy editor.

SAPIENS is an editorially independent magazine of the Wenner-Gren Foundation and the University of Chicago Press. SAPIENS: A Podcast for Everything Human is part of the American Anthropological Association Podcast Library.

This episode is part of the SAPIENS Public Scholars Training Fellowship program, which provides in-depth training for anthropologists in the craft of science communication and public scholarship, funded with the support of a three-year grant from the John Templeton Foundation.

Cementing the Past

Eshe Lewis: What makes us human?

Anahí Ruderman: Truly beautiful landscapes.

Nicole van Zyl: The roads that I use every day.

Thayer Hastings: Campus encampments.

T. Yejoo Kim: Eerie sounds in the sky.

Eshe: What makes us human?

Cecilia Padilla-Iglesias: Division of labor.

Charlotte Williams: Colonialism.

Giselle Figueroa de la Ossa: The value of gold.

Dozandri Mendoza: Fun. Dance.

Justin Lee Haruyama: Cultural and social interactions.

Luis Alfredo Briceño González: Hopes for a better future.

Eshe: Let’s find out! SAPIENS: A Podcast for Everything Human.

Eshe: In this global moment, companies control a lot. And with CEOs like Elon Musk selected for American governmental positions, the lines between political and corporate power are somehow more blurred than before. It might seem like an unprecedented moment, but the U.S. government has a long history of ties to corporations. These ties affect our presents and our futures. But, oddly enough, they also affect the past—even the ancient past.

In this episode, we speak with anthropologist Charlotte Williams and learn about her investigations into how one particular American corporation came to dominate not just the control of agriculture, but also the control of archaeology.

Eshe: Hello, Charlotte.

Charlotte Williams: Hi, Eshe, how are you?

Eshe: I’m good. I’m so excited to be speaking with you today. Can you please introduce yourself?

Charlotte: Yeah, so I’m Charlotte Williams. I’m a Ph.D. candidate in the anthropology department at the University of Pennsylvania and a Mellon fellow at Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, D.C. My research focuses on archaeological landscapes in Central America that were subject to United States imperialism.

Eshe: OK. So I’m going to ask you to talk a bit more about what you mean by American imperialism.

Charlotte: Sure. So, I feel like when we come across terms like colonialism or imperialism, we might kind of think of the British Empire or the East India Trading Company as kind of a corporate empire that influenced geopolitical decisions throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. American imperialism refers to the idea that America actually has been in the business of empire since its formation. And as part of this, the United States is often entwined with companies. So, there’s a kind of notorious quintessential company in Central America that was entwined with United States politicians, and that’s the one I’m most concerned with, the United Fruit Company. I don’t know, have you heard of the United Fruit Company before?

Eshe: I have, but for people who don’t know, can you tell me a bit about the United Fruit Company?

Charlotte: Yes. So if you’ve ever heard of the term “Banana Republic,” that term, which can also be kind of derogatory, refers to this company. Um, and the idea was that it’s so powerful that it basically became its own country or its own republic. It was in operation from 1899 through about the 1970s. And the reason I’m most interested in it was because it was the largest landholder in Central America for that duration of time. It was a very shady monopoly. It is known for stamping out labor reform. It is known for sponsoring coups of democratically elected leaders throughout Central America when they were concerned that the people elected would not really jive with their land politics. And oddly enough, in all of those land projects, the company also engaged in archaeological research, and that’s where I come in.

Eshe: OK, so, the United Fruit Company, Banana Republic, for people who didn’t know but might be able to guess from the term, they also were very involved in the production of, um, and harvesting of bananas.

Charlotte: Yeah!

Eshe: Right. But I guess with that much power and that much, involvement in agriculture and in politics, I guess I’m wondering about this archaeology piece. I did not know about that. So why would they invest in archaeology and how?

Charlotte: Yeah, that’s, I mean, this is what ignited my dissertation research. Because in addition to bananas and sugar cane and all of these, I mean, really extractive enterprises that they engage in, they also engage in extracting archaeological resources, and sponsoring archaeological research. And I’ve been trying to kind of untangle the company’s involvement. And increasingly, a couple more scholars are also interested in United Fruit archaeology. So, I actually, found out more by talking to Sam Holley-Kline, who is going to help us understand more of the context.

Sam Holley-Kline: I currently hold a fellowship from the American Council for Learned Societies. And I was most recently a collegiate fellow in the University Honors Program at the University of Maryland. My research focuses generally on the history and politics of archaeology in Latin America.

So, basically, the United Fruit Company was founded in 1899 as the merger of a couple of more regional interests based especially in the production of bananas, sugarcane, and shipping.

So, the company would do things like make deals with governments to build railroads. They’d say, “Hey, we’ll build you a railroad to the Pacific and won’t that be great for your country? And, hey, in turn, why don’t you just give us all the land along the railroad?” Countries are like, “Yeah, that sounds like a good deal.”

The company eventually came to control land and production in a way such that it had pretty strong influence over a lot of governments, especially in Central America. Now that’s where we get the term “Banana Republic,” right?

Charlotte: You know, enfolded into those territorial projects are also what we’ve been kind of looking at, which are archaeological sites. So, I’m wondering how you came into researching United Fruit Company’s involvement in archaeology? And what have you looked at so far?

Sam: I took some time to do archival research at the Carnegie Institution for Science. And when I was going through those archives, you know, I kept seeing the United Fruit Company. It was not always as direct as I might have imagined, right? But it was, you know, it was kind of octopus-like, right? You know, the funding, the logistics, the discounts on passage, permission to use the railroads, housing in the United Fruit Company borders, right? Friendships between United Fruit Company folks and archaeologists. It was sort of everywhere but in a way that was kind of difficult to pin down.

Charlotte: Yeah. So, I will, I’ll interject here because in talking to Sam, I had a similar experience in doing this research where I kind of came into United Fruit archaeology by accident, which is in doing archival research about certain archaeological projects in Central America, you’ll often find things like, oh, this box was shipped by the United Fruit Company. Or oh, this archaeologist asked a United Fruit Company plantation owner if he knew of laborers who could work on the site. Or this person had a ticket that was covered by the United Fruit Company for transportation and access.

And so it’s kind of interesting because the company is kind of everywhere all at once but still kind of invisible. And part of the issue is that there’s no company archive, like a corporate record. Often researchers don’t have access to it. They destroyed a lot of their records. I asked Sam in the course of our interview if there were really famous or quintessential United Fruit Company projects. This is what Sam had to say.

Sam: Yeah, I think there are two main ones. The first is Quiriguá. It seems to me that sort of the height of, you can call it United Fruit Company archaeology, has to be Zaculeu.

Charlotte: So, he mentioned two sites, Quiriguá and Zaculeu, and the Quiriguá is the first site that the company just outright buys in 1910. Quiriguá is a Maya site in Guatemala, and they basically kind of create this mini conservation project in the middle of a banana plantation. But they also invest in other sites, like in Bonampak in 1947, which is a site in Mexico. They subsidize research. Um, but what I want to focus on is that other site that Sam mentioned, which is the site of Zaculeu, and it’s probably the most notorious United Fruit Company project.

Eshe: OK, I’m excited, but also very nervous to ask, what happened at Zaculeu? Can you give me some context? Where is it? What is its significance?

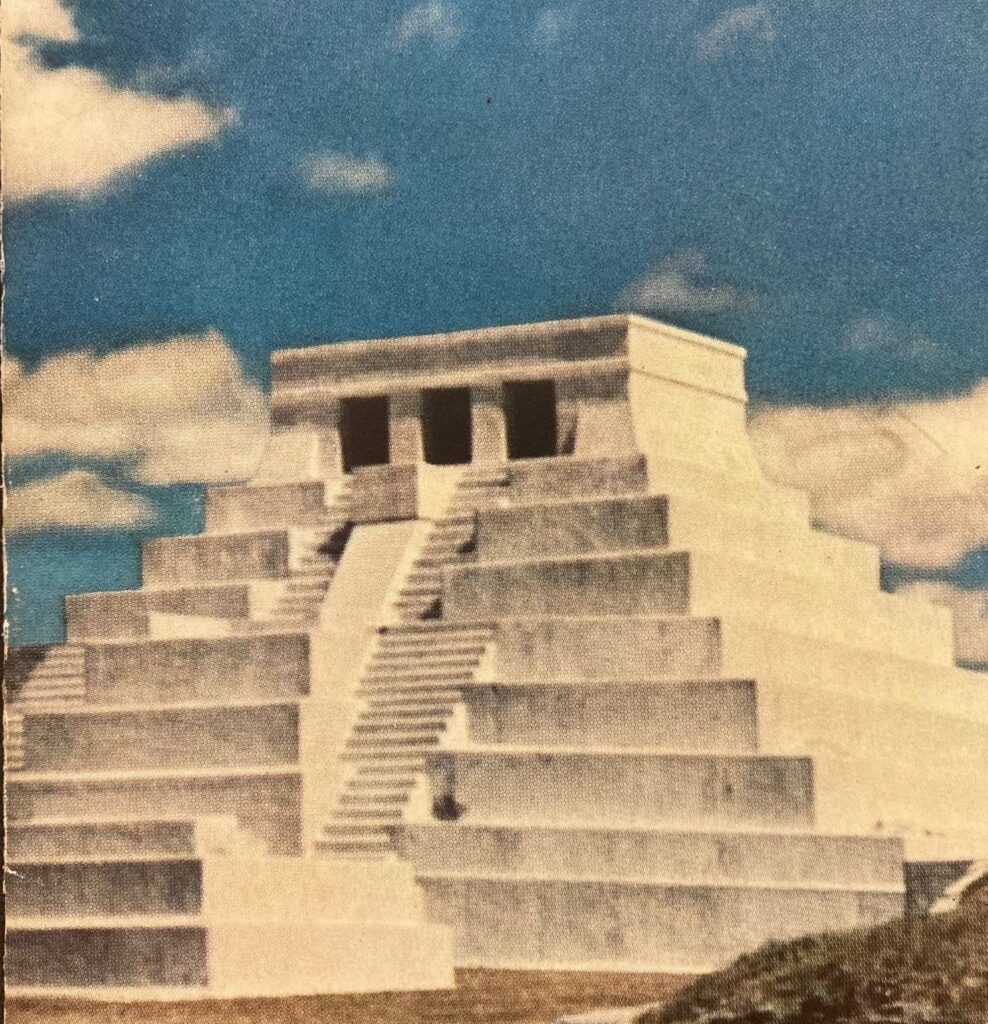

Charlotte: Yes. So Zaculeu is a site located in the west of Guatemala near the town of Huehuetenango. It is a Mam Maya site. It has a lot of monumental architecture. It has stepped pyramids. It has a ball court. But as you are rightly scared to ask in the 1940s, the United Fruit Company kind of comes on the scene in which they stage a conservation project that has pretty lasting repercussions today. So the company in 1946 decides that they’re going to do this goodwill project; they’re going to restore a site for the Guatemalan government, and they want to make it look as though no time has passed, as if people just kind of picked up and left the site. In order to do this, they basically cover the site in thousands of metric tons of cement. And painted it bright white.

Eshe: Are you serious?

Charlotte: I’m serious. Yeah. It was a really aggressive means of conservation.

Eshe: I would hope that this is like, not only does this not sound like standard conservation practice, I would hope that it wasn’t even at that time.

Charlotte: I mean, it’s an anomaly now, and it was also an anomaly then. I’m not a conservationist, but from what I understand, standard practice now is to make things at least reversible. So, it comes with the understanding that people are always researching sites and finding out new information. We should be able to adapt how things look as we learn more. At the time, that was still seen as a pretty egregious move.

Eshe: I’ll talk more with Charlotte about her research into the United Fruit Company after the break.

[BREAK]

Eshe: Welcome back. Before the break, I was talking with Charlotte Williams about the United Fruit Company’s involvement in archaeological restoration projects in the early 20th century, and how they were less like restorations and more like a revisioning of the past. Let’s pick up our conversation.

Eshe: I have so many questions. Like, if this is not reversible, then what does that mean for people who are working on those sites or living around those sites today?

Charlotte: Yeah, the site is still affected by these choices. And as you point out, you know, in your question, like, who was responsible for this?

The leader of the project is John Dimick. He’s this kind of really interesting character. And also was at one point contracted by the Office of Special Services, which is a precursor to the CIA. So, he’s very entwined with espionage in the United States. And I know, I mean, this sounds kind of so overblown and like a conspiracy theory, but this is true. He published a memoir and references this. So, yeah, so this is the man who’s, um, kind of in charge of securing the funding of the project. He contracts a number of archaeologists, who make some pretty radical decisions at the site. And I was curious about some of those decisions and what they mean. To find out more, I interviewed Victor Castillo. Victor is an archaeologist with an immense amount of expertise on the site of Zaculeu.

Victor Castillo: My name is Victor Castillo. I am a research assistant professor at the Institute of Archaeology in the Jagiellonian University in Krakow, Poland. So I was born and raised in Huehuetenango, not too far from Zaculeo. So for me, Zaculeo was always an important site, an important place for which I have a lot of curiosity.

Charlotte: I was wondering if you could provide a little bit more background about how United Fruit became involved in the project and what the implications of that became for the site?

Victor: The United Fruit Company sponsored and directed this archaeological project at Zaculeu from 1946 to 1949. This was not only an archaeological research project, but the main objective, the main goal of this project was to reconstruct several buildings at Zaculeu in a way that they would, uh, remain forever unaltered.

Charlotte: Hmmm.

Victor: And this happened in a very tense, in a very complicated political context. It was the first years after the democratic Guatemalan revolution. And, of course, there were some conflicts between the revolutionary government and the United Company.

Charlotte: It seems it’s taking place at this incredibly tense political moment. But as you say, they choose to restore the monument in an incredibly, let’s say, enduring or unalterable way. And I’d love to hear you talk a little bit more about what that actually meant. I mean, what did this conservation project entail, and why is it so significant even now?

Victor: Zaculeu is an archaeological park open to the public, and actually, it gets thousands of visitors every year. So, when those visitors get to the site, the first thing that they notice are those gray structures, those gray pyramids and stepped platforms. And that’s nothing less than old concrete, old cement. So the reconstruction of those structures was very aggressive, very unorthodox for modern standards, I would say, because reconstruction used modern materials such as steel, iron, concrete. So that sort of damaged the structures from the perspective of the conservation of archaeological remains. Because this over-emphasis in creating something that would never be destroyed, altered the structures in such a dramatic way.

Charlotte: I’ve seen in some of the pamphlets and public relations material that the company produced that they advertise it as kind of gifting a modern monument. So, it seems that the aggressive means of using concrete, producing very crisp lines seems like it was a very deliberate attempt to make something seem maybe more futuristic. I don’t know if that resonates with you at all or if that’s a correct interpretation.

Victor: Absolutely. They were creating this sort of fantastic city. And the reconstruction of the site of Zaculeu was criticized starting in the 1940s. Archaeologists and experts noticed that this reconstruction was just going beyond what was accepted in terms of restoring archaeological monuments, even by the standards of the 1940s.

Charlotte: So, I think at least what Victor’s expertise revealed to me is that not only is this restoration project really inaccurate, but it also damages the possibility of finding more in the future, in some ways, meaning that because it’s so irreversible, excavating some of the structures would actually require things like jackhammers.

Eshe: OK, I’m thoroughly stressed out. Enlightened, but stressed out. I kind of want to zoom in a bit on what you just said about the impact now in terms of what interpreting that site means in light of this. So, does anyone have a sense of what it should have looked like?

Charlotte: Yeah. That’s a great question. And I literally asked Victor the same thing because I’m also confused of, you know, how do we actually know what it may have looked like for the people that lived there and made their lives there? So, yeah, I asked him the same exact question.

Victor: We know that, in the past, those structures were covered with a thick layer of stucco. That’s the name that we have for this mix of lime and sand that was used as a coat to cover the structures. And the structures were painted with red and other colors. So the view of the city should have been really impressive. This colorful place that probably received pilgrims and people during market days, for example. A city full of vibrant colors and sounds, which contrasts with what we see today, which is the contrast between the gray matter of the concrete and the green grass.

Charlotte: Right.

Victor: Back in the day, this was a city full of life and color.

Eshe: So, completely different. You know, thinking of what you could be seeing and then what is there, it’s such a loss.

Charlotte: It’s literally kind of whitewashing the past. And so I think in the 1940s, what’s happening is archaeologists are finding remnants of color, but they choose to ignore those because it doesn’t kind of fit. It’s not modern enough. And so we lose that really colorful context now. And it’s a shame because not only are we losing that vibrant color, but now because of the stain of the United Fruit Company on this site, Zaculea’s really famous because of the United Fruit Company and not because of the incredible history that the site actually exhibits. And, as Victor was highlighting for me, it also impacts the way that the United Fruit Company’s involvement in the site impacted the way the site was conserved, but then also impacted the way that artifacts were recovered and stored.

Victor: So the artifacts recovered during the archaeological excavations sponsored by the United Fruit Company were never sent to the National Museum of Archaeology in Guatemala City. So, the United Company decided to build a small exhibition room at the site. And all the artifacts recovered during the excavations were stored there in that small museum until 1980 when the museum was burnt during the Civil War, which in this part of Guatemala was particularly violent.

For many fronts, the archaeological collection of Zaculeo was neglected. And that’s unfortunate because the collection has some of the most incredible artifacts recovered in Maya archaeology. And, our knowledge about those artifacts is tainted, I would say, by the imprint of the United Fruit Company. Because for the general public, archaeologists, Zaculeu is immediately associated with the United Fruit Company. And there is a larger, very interesting history that has been obscured by that association.

Charlotte: If there’s anything else or important that you want to make sure is known about Zaculeu that doesn’t have to do with the United Fruit Company, what would that be?

Victor: I would say that it’s the long and complex history of interaction with other parts of the Maya area and Mesoamerica and even southern Central America, for example. So we know that Zaculeu interacted with those regions because the number of exotic artifacts that have been found in Zaculeu is really, really incredible.

So we have, for example, turquoise from northern Mexico. We have metals such as copper from Oaxaca. Tumbaga from southern Central America. We also have evidence of trade with the Mixteca, and even the architectural style of the last phase of construction was probably inspired by northern Yucatan architecture. And it’s this interaction, this connection with different peoples and with different regions, that makes this site truly crucial and important for understanding the history of the ancient Maya and the patterns of trade and interaction that we see in the archaeological record.

Charlotte: I think what becomes apparent is Victor is very passionate about trying to kind of correct this record and reinvesting, kind of, intellectual work into the site. And looking at structures that the company did not encase in cement because it wasn’t the entire site. So, there’s still some buildings that kind of contain information.

And if everything goes through, Victor would be the first person to excavate the site since the United Fruit Company did in the 1940s.

Victor: We are commemorating the 500 years of the resistance of Zaculeu against the Spanish invaders. So this is going to be a period of remembrance, of questioning, of assessing what we know about Zaculeu and its history. So, I have planned archaeological research, and this is really exciting because this is the first archaeological project in almost 80 years, the first archaeological research after the United Fruit Company project.

Eshe: That’s amazing! It sounds like we might get some information. I mean, even more than what Victor has been able to glean from the research that he might have done so far. So that is very exciting. I’m very excited for some non–United Fruit Company data and intervention. I just don’t understand why they would get involved with archaeology in the first place. Like, do you have any sense of what they get out of it or what they got out of it?

Charlotte: Yeah, it’s such a good question. The company was engaged in all kinds of what they called “goodwill projects” or kind of showing that they had corporate responsibility. They built hospitals, an agricultural school. And I think, honestly, archaeological sites may have been pretty inexpensive means of doing a goodwill project. You only have to maintain it for a couple of seasons. You can take a lot of pretty pictures and print them out and circulate them. And at least in Zaculeu, I think what’s also happening is because at the time, a lot of national archaeological offices were under the umbrella of education, that the company could also use this as a way to conduct research and promote goodwill without getting taxed on goods and stuff brought in if it was for education. I think it’s born from the interest of a few powerful men in the company that are just interested in archaeological work. They need to promote the company and make it look good, and this is a way to do that.

Eshe: That’s fair. I guess we can still see that strategy today, right?

But I think I just want to connect the two. Like what does investing in archaeology do for their image that, you know, other endeavors don’t?

Charlotte: I’ve thought about this, too, because why is it archaeology? But I also think that archeology as an educational discipline allowed them to perform science for a public in a way that isn’t maybe possible in a place like a hospital or a school. At Zaculeu, they invited tourists to come see the conservation project in action. Archaeological sites are ways that they could invite diplomats and politicians and tour them around. These are really kind of highly aesthetic and politically potent landscapes. And so I think there’s an element of performing archaeology, and, without maybe oversimplifying it, there’s kind of a narrative of, “look we can conserve your past for you. We control your past and your present and your future.” So, I think that it’s symbolic. It gets to sit under this umbrella of being for an educational project, and it’s politically useful.

Eshe: Yeah, I mean, again, it reminds me very much of, you know, other colonial endeavors like the World Fair, right?

Charlotte: Yes.

Eshe: Sort of like paternalistic, but also voyeuristic and, disturbing, practice of spying on people or putting people on display for those who live in the heart of the empire and also reinforcing a power dynamic, right?

Charlotte: Yeah, there’s a, there are lots of parallels between archaeology and things like World’s Fairs. They’re different ways to do these publicity stunts, but I think for many companies throughout time, that’s been a useful and kind of successful way to do it.

This kind of reminds me of a portion of conversation that I had with Sam Holley-Kline, the researcher I introduced at the beginning, trying to understand what archaeology specifically is doing. So, this is what Sam had to say.

Sam: Archaeology is maybe apparently unproductive at first glance. It seems like it’s just able to hide behind the veneer of pure science. So, you can actually see the experience so that this value neutrality of science maybe in ways that maybe you can’t in all fields.

Charlotte: So, yeah, I think there’s a, what Sam is calling the value neutrality of archaeology is being kind of a neutral zone that just works well for the company in ways that, even though they’re deeply entwined in their own enterprises, they can kind of mark it as something separate and distinct.

Eshe: So, what becomes of these sites eventually? Like, you’ve talked a lot about Zaculeu, but there are a number of them. What does the aftermath look like for these areas?

Charlotte: Yeah, after the United Fruit Company dissolves and forms into what we now know today as Chiquita Banana, many sites are enfolded into state-sanctioned archaeological projects. Meaning that the state of Guatemala or Mexico creates these zones as public archaeological parks. A lot of those parks still bear the scars of United Fruit archaeology, I would say. So, for instance, the site of Quiriguá in Guatemala is still surrounded by active banana plantations. But, as we know, the more we research them, the more we understand how expansive they were. And we find all kinds of things through things like land surveys and reconnaissance. So that core of Quiriguá that was determined by the company in 1910 is still the core that is maintained today. It’s the same boundaries that UNESCO recognizes for the site. In this discussion, Zaculeu is probably the most famous one for being kind of literally and figuratively cemented in a fabricated past.

Eshe: But I would like to know from you, what do you take away from this research?

Charlotte: I think one of the most important aspects is that we have to take seriously how entities like the United Fruit Company, or what some scholars are kind of calling company states, really influenced the production of the past. Modern countries will use archaeology in their own national stories. And that impacts the way that we review the past. But the United Fruit Company was ostensibly its own country, right? So, if it has its own police force, if it has its own labor laws and land policies, I think we have to kind of see the company as this invisible, but very present country, that impacted geopolitics with very visible evidence in our current landscapes but also in the landscapes of the past.

Eshe: I want to ask you all about what that means for American imperialism today as it continues and what we’re learning.

Charlotte: American imperialism is an active project. It did not end with the United Fruit Company. Whether it’s supplying weapons that destroy not only current landscapes, but historic ones. And wiping out historic landscapes is a form of ethnic cleansing. It’s a war crime as defined by many international bodies. I do think we really need to take seriously how American empire is impacting our access to the present and our access to the past, which helps us to make sense of ourselves.

Eshe: Yeah, absolutely. Those are some really powerful questions, and I cannot wait to hear the answers. Charlotte, thank you so much for joining me today.

Charlotte: Thank you so much for talking with me. I really appreciate it.

Eshe: Charlotte Williams is a Ph.D. candidate in anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania. Her research explores how archaeology has been used in American imperial projects, with a focus on the United Fruit Company in Central America.

SAPIENS is hosted by me, Eshe Lewis. The show is a Written In Air production. Dennis Funk is our program teacher and editor. Mixing and sound design are provided by Dennis Funk and Rebecca Nolan. Christine Weeber is our copy editor. Our executive producers are Dennis Funk and Chip Colwell. This episode is part of the SAPIENS Public Scholars Training Fellowship program, which provides in-depth training for anthropologists in the craft of science communication and public scholarship, and is funded by the John Templeton Foundation.