The Day I Heard My Mother’s Accent

Throughout my early childhood, I did not hear my mother’s accent. Other people seemed to notice it, however. In the provincial French town where we lived, my classmates often stopped by for an impromptu snack after school, which frequently turned into dinner or a sleepover.

“I love your mother’s accent,” my friends would say on meeting her for the first time and taking in her hospitality.

I genuinely did not know what they were talking about. To me, my mother’s voice was simply home.

That changed one day when I was around 10 years old. My mother was on one of her long phone calls from our home in France to her sister in Syria, speaking a vernacular mix of French and Arabic from the corded telephone in her bedroom. I was reading a novel by her side, lying on the bed, when I suddenly noticed the musicality in her flow and the way she rolled her R’s. Her intonation, I recognized for the first time, was “Middle Eastern.”

By then, I had understood that she did not exactly blend into my daily surroundings. My mother consistently shined with elegant outfits in town, then changed into an embroidered abaya as soon as she passed through the door of our flat. But it wasn’t until that day that I fully saw my mother as others in the town might have seen her: as “Oriental.” The familiar comfort of our home, and my relation to my mother’s voice—and to the world—became, in an instant, tinted with exoticism.

I was raised by a Syrian mother and a French father. My parents met at a Canadian university in the late 1970s, got married, and had my sister and me. The four of us eventually relocated in 1985 to my father’s hometown of Clermont-Ferrand, in the center of France—an underrated city where the streets are paved with black lava stone quarried from the surrounding mountains. I was 2 years old and my sister was 4. Our flat was just a short walk from my paternal grandparents’ house and from my great-grandmother’s apartment.

Syria seemed far from this reality; my paternal grandfather once told me that when my father called him from Canada to announce he was engaged to a woman from Lattakia, a Syrian Mediterranean city, he had to buy a travel guide. In his mind, Syria was entirely made of desert.

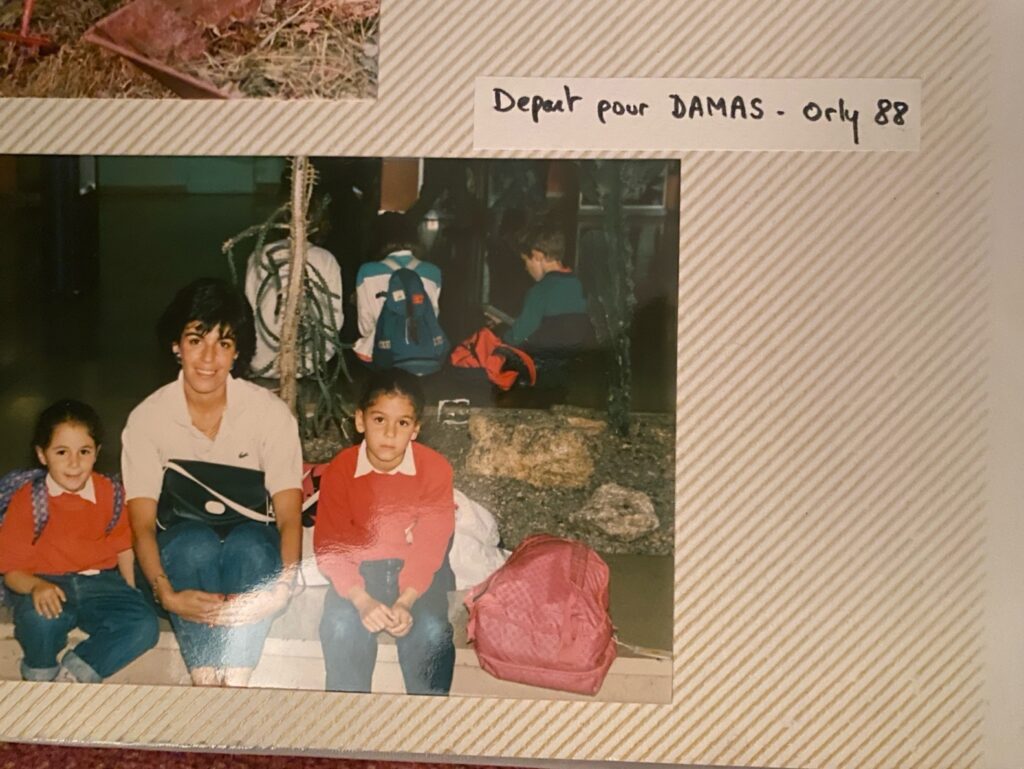

Despite the physical distance, I always felt connected to my mother’s side of the family. Though I rarely encountered people of Syrian descent in our part of France, other Syrian family members and friends living in the diaspora in Lebanon, Cyprus, the U.S., Canada, and Paris were part of my world growing up. We also visited my grandmother, Tata Elly, and my mother’s younger sister in Syria during the school holidays.

I cherish the memories of those long summers spent in complete immersion in my mother’s native neighborhood. We were awoken early in the morning by the calls of street vendors selling watermelons, enjoyed outrageously generous meals shared with relatives and friends, and spent hot afternoons at the beach. My sister and I understood our mission while in Syria was to make the most of time with our loved ones; historic sites visits were rarely on the program.

Living in this bicultural way felt normal to me as a child. But in the moment I heard my mother’s accent, I discerned what the poet Miguel Zamacoïs calls the “invisible luggage” of speaking a language in a way that differentiates one from the majority group. Did it become my luggage too? Or was I, maybe, distancing myself from it by rendering it tangible?

Without knowing anything about the formal discipline of anthropology, the realization of my mother’s accent was a first step toward my becoming a member of the field.

For sociocultural anthropologists like me, the questions that trouble us most about people and society often reach deep in our personal history. As a university student, I was taught to “think anthropologically,” which meant I was trained to perceive the patterns of everyday life that others take for granted, and interpret how the mundane connects with the political to shape diverse worldviews.

At a young age, I had unconsciously allowed the external representation of my mother as “Other” to enter the family space. Later I read Palestinian American scholar Edward Said’s seminal work Orientalism on the enduring representation of those from the “Orient” as “Other” within European-centered narratives. If, as in my case, the “Other” is also part of oneself, one can feel an urgency to escape simplistic, dualistic outlooks on the world.

Hearing my mother’s accent was not accidental. It resulted from a gradual buildup of experience of dissonance.

As I became a scholar and embarked on my own in-depth research on borders and migration, I became obsessed with dismantling categories of “Otherness” and challenging assumptions about belonging, place, and identity. I spent several years exploring the realities of Iraqi artists and intellectuals living in exile in Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon in the aftermath of the 2003 U.S.-led invasion of Iraq. I was not consciously drawn to Syria, but working in the capital of Damascus, in a familiar (yet not too familiar) place, molded the questions I asked about belonging and my relationships with my research participants.

Without often realizing it, I carried a share of my mother’s invisible luggage as a researcher. This luggage felt heavy at times. For example, during Bashar al-Assad’s dictatorship—from 2000 to 2024—I had to be cautious that my writing about Syria published in academic journals would not threaten the safety of my loved ones still living in the country. Assad’s political surveillance apparatus and brutal dominance created an entrenched tapestry of fear. What one wrote or said, and to whom and from where, could endanger Syrian people. The core of my anthropological work over the past 15 years has been documenting how people who have crossed a border care for others in times of crisis, often channelling their experiences to unsettle state-centered narratives about who belongs and who does not.

I recently asked my sister if she shared the same experience of hearing our mother’s accent as a child. She told me that for as long as she can remember, she has been acutely aware of our mother’s accent. At recess on our primary school’s playground, I used to display my broken Arabic to my classmates, teaching anyone who was interested how to count to 10: “wahed, tnein …” Meanwhile, my sister kept a low profile, avoiding attracting attention to our Syrian lineage.

Growing up, I felt that the palette of emotions made available to me to describe my dual heritage was often reduced to feeling either pride or shame. However, in reconnecting to the gaze of my 10-year-old self through an anthropological lens, I’ve created space for a more nuanced understanding of the in-between spaces that many diasporic families navigate.

The experience of recognizing my mother’s accent resonates, for instance, with anthropologist Clara Han’s commitment to center ethnographic accounts of a child’s perspective in Seeing Like a Child. Han’s stories of her everyday experiences growing up with Korean immigrant parents in the U.S. pave the way for other anthropologists to explore how children from migrant families assemble and make sense of the layers of estrangement they are exposed to in a society.

For me, that meant reconciling contrasting intimate lived experiences of being seen as both “belonging” and “not blending”: noticing people’s reactions to my typically French family name, receiving a teacher’s comment on the darkness of my hair, or witnessing a stranger asking my mother to repeat a sentence one time too many amid her fluency in French.

These layers of estrangement grew with time as I encountered how many people remained oblivious of Syrian history, politics, and culture. I often found myself giving a history lesson about France’s colonial rule over Syria from 1920 to 1946 or having to explain my family’s Christian religious background. (Though a majority of Syria’s population is Muslim, Syrian Christians are one of the oldest Christian communities in the world. When I was growing up, they were estimated to account for over 10 percent of the population.)

In France, integration is underpinned by universal principles that claim to transcend ethnicity, religion, and gender. Yet many immigrants to the country are still persistently asked the question, “Where are you from, originally?” This disjuncture leads to those who do make up the country’s diverse populations often feeling invalidated by a restrictive national narrative.

We all talk with an accent. We phrase our sentences according to the language(s) we use, with influences from the people who raise and educate us, and flavored by the places where we live. All of this can shift according to who we are speaking with, how long we live in a place, and countless other factors.

But the phenomenon of suddenly hearing a parent’s accent stands apart. For me, in that moment the bond between parent and child was rendered permeable to societal pressures to “integrate.”

I started this essay with an urge to unpack this split second in my life. Hearing my mother’s accent was, however, not accidental. It resulted from a gradual buildup of experiences of dissonance.

It is not a coincidence that I am revisiting this moment now that I am myself raising children in England, a country where I do have an accent. My French-accented English will be detected by some readers in these very lines and certainly feels loud at times for students when I teach at my university in London.

But my experience of speaking with a French accent in London resonates very differently from my mother’s experience of carrying an Arab accent in France. The day I heard my mother’s accent, I heard the colonial echo of a society grappling with the racialization of some of its members, and my body accepted it and rejected it all at once.

Until today, these questions around belonging remain largely unspoken in my family. As I was growing up, the deep sense of self-worth and pride instilled by my mother toward her ancestry made me feel that if anything, others were lucky to be exposed to our heritage. I can now discern some of the more painful layers hidden underneath my mother’s stance. But I want to hold on dearly to her assertive and accented way of being in her world.

I have not inherited my mother’s accent—but I proudly carry a share of her invisible luggage with me each day.