Wisdom Without a Country

I scour photos of the studio for clues to what it might have been like for you to wake up there in the morning—to feel the light tingle of sunshine across your brow as it poured through the skylight just above the raised sleeping loft. The bed is a wooden plank with a handcarved headboard, chiseled from memory to mimic one remembered from the small village of Hobița, a frieze of geometric shapes. Dust motes sail through the light, tiny golden ships, as you stretch. Below, you can see a rough circular table surrounded by low, carved wooden seats. There is a chest with a blanket and pillow thrown on it, a book still open from last night’s reading, a coffee urn, an empty brandy bottle. And in the corner, a flashing spot of brilliance where the androgynous “Torso of a Young Man,” cast in shiny new brass, sits on top of a rough log near a pile of rocks stolen from the Paris catacombs that will maybe one day be transformed into sculptures. Leaning on the pile, half a plaster cast, is a woman; her face is smooth, a distillation. It’s no longer clear who she was, and she has no arms. Maybe you will move the sculpture closer to the window so that its shadow will dance along the unadorned white wall below the loft as the day continues to open up. Maybe nothing will change.

The life of Romanian sculptor Constantin Brâncuși became my fantasy in the early days after the results of the 2016 U.S. presidential election were announced—during the hours when screens screamed at us about evil, arrogant stupidity: efforts to encourage vile racism, end health coverage for the most vulnerable, thwart education, and stop the movement of people and ideas across borders. It was a dangerous time, and if you were prone to flights of fancy or apocalyptic terror, it was hard to take a mental step without falling into a sinkhole.

Brâncuși lived through two world wars in his studio at the end of a dusty lane in Paris, France. He stayed in his space with a limited number of objects and distractions—simple pieces to be arranged and rearranged, a commitment to what was right there. He lived with his creations, would weep when they were sold. His favorite way to display his work was simply to invite someone he liked over for a drink and a tour. Maybe his choices weren’t just political escapism or artistic privilege; maybe they were a message.

The stack of books in my living room about Brâncuși and the images of his bird sculptures elongated like flame toward the sky brought me comfort in those early days. They inspired me to give myself a challenge:

You will not throw away all the work you were doing, the stories and articles you were writing before the election, even if it seems like everything should focus on fighting the current administration and its vigilante thugs in the streets. You will stick with Brâncuși; you won’t abandon him. You will keep arranging and rearranging the things that matter—that mattered before this president and that will matter after him. You will not let him or his cronies convince you that your work is unimportant.

This is the trick of authoritarians: to convince you your reality is not reality. To tell you your neighbor is your enemy. To frighten and upend. To make the future all about them.

Many of us were thinking about art and exile in those first weeks because they seemed like the two best options for survival. Brâncuși had been teaching me about both since the summer of 2016 when we visited my husband’s family in Romania. On a hot day driving around Bucharest, the country’s capital, I had been startled by an enormous sign draped across a building reading: Brâncuși e al tău așa cum și țara asta e a ta (Brâncuși is yours, just as this country is yours)—and alongside this message, an image, taller than an office building, of a stone woman.

The woman is a deep sepia color, seated, clutching herself. Her name is Cumințenia Pământului (“The Wisdom of the Earth”), or C.P. She is a well-known piece by Brâncuși, blown up to extravagant proportions on the banner so that her details are arresting. “Wisdom” has a sanguine, if slightly exhausted, expression. She is naked, and she looks postpartum to me; I see myself five years ago, weaning my son off the breast, a full body slowly deflating, and tired—but sated somehow. Is that the wisdom of the earth you meant, Brâncuși?

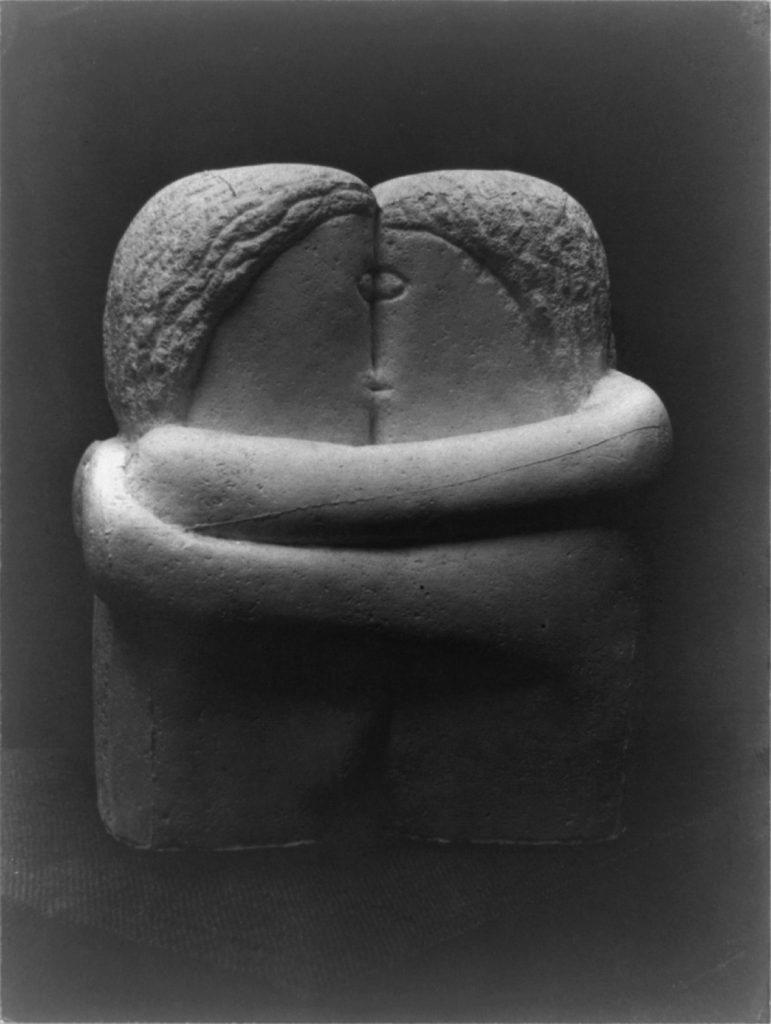

I love the sculpture, and I ended up falling in love with all of Brâncuși’s work—his odd eggs, endless columns, and small kissing couples. They have a simple elegance but also a solidity that holds the viewer to the earth. And much of his work expresses his sense of humor. When I look at “Mademoiselle Pogany [I],” I sigh, puzzle, and laugh all at the same time.

On that day in Bucharest, I asked my mother-in-law, “What is that, mama? What is the story with that sculpture?” Well, there was some effort to move it to New York or Paris or someplace like that, she said, but the Romanian people want to buy it. The original owner’s family members, the executors of his estate, want many millions of euros for it, and the Romanian government doesn’t have enough money, and so they set up a campaign. Every person is being asked to give what they can. And this is wonderful, she added, because the sculpture should live in Romania.

“Tell me! Tell me!” my 5-year-old son yelled. “Tell me what buni [grandma] is saying!” So I translated the basic story to my son in English and added, “You see, they don’t really need another famous sculpture in New York or in Paris, but here, in Bucharest, it would really matter.” I’m slightly shocked by my own quasi-patriotic response, the strange and awkward work of being a foreign parent helping a child navigate his hyphenated Romanian-American heritage.

“I have 20 euros. Can I give it?” he exclaimed.

“That’s a good boy,” his grandmother said, beaming. “No, honey, you keep your money, and buni and bunu will give in your name, okay? In September, we’ll give the money.”

This placated my son, and he happily kicked the back of his grandmother’s seat. “We’ll get the statue for Romania,” he said.

In February of 1876, Brâncuși was born in the village of Hobița, in Oltenia, which is part of southwest Wallachia, one of the three regions that make up modern Romania. His upbringing was rural and religious, and art was an everyday thing—but that was not the word anyone used for the beautiful, bright textiles and handcarved wood that covered everything in a peasant household in 19th-century Romania. At age 18, he was sent to the Craiova School of Arts and Crafts, where he studied furniture building.

By 1898, Brâncuși began his training at the Bucharest School of Fine Arts and was quickly celebrated for a dazzling technical skill that was best captured in the “Flayed Man” sculpture he created for a local medical school. He later referred to the anatomically accurate piece as “beefsteak,” saying it exemplified all that was wrong with the sculpture of his day—its commitment to realism at the expense of the more artistically and philosophically interesting “essences” of things. For Brâncuși, the essence of a thing was comprised of its most basic forms—a curve, a gesture—and could not be captured by an exact reproduction. Imitating or mirroring physical forms denies the life inside the being or the object that is represented. More importantly, reproduction dishonors the life of its medium. Brâncuși sought to enter the stone or wood and release its spirit, which was always, for him, an echo of a universal spirit.

Largely on foot, Brâncuși journeyed from Bucharest to Paris in 1903 and 1904, without a plan except to make it to the capital of art. Eventually settling in Montparnasse, a neighborhood that was home to many important figures in the history of modern art, literature, and music such as Henri Matisse, Tristan Tzara, Erik Satie, Marcel Duchamp, and Guillaume Apollinaire, Brâncuși turned himself into one of the great sculptors of the 20th century. Art was everywhere and everyone was making it. Brâncuși got drunk with the painter and sculptor Amedeo Modigliani. He and Pablo Picasso kept a cool distance, maybe to accommodate their large egos. For a brief period, in 1906, he was taken on as the apprentice of Auguste Rodin. Set to build an entire career on his reputation as Rodin’s talented protégé, Brâncuși reportedly threw a drunken temper tantrum in a local cafe and denounced Rodin and all those like him—those purveyors of beefsteak who didn’t understand what sculpture was really for.

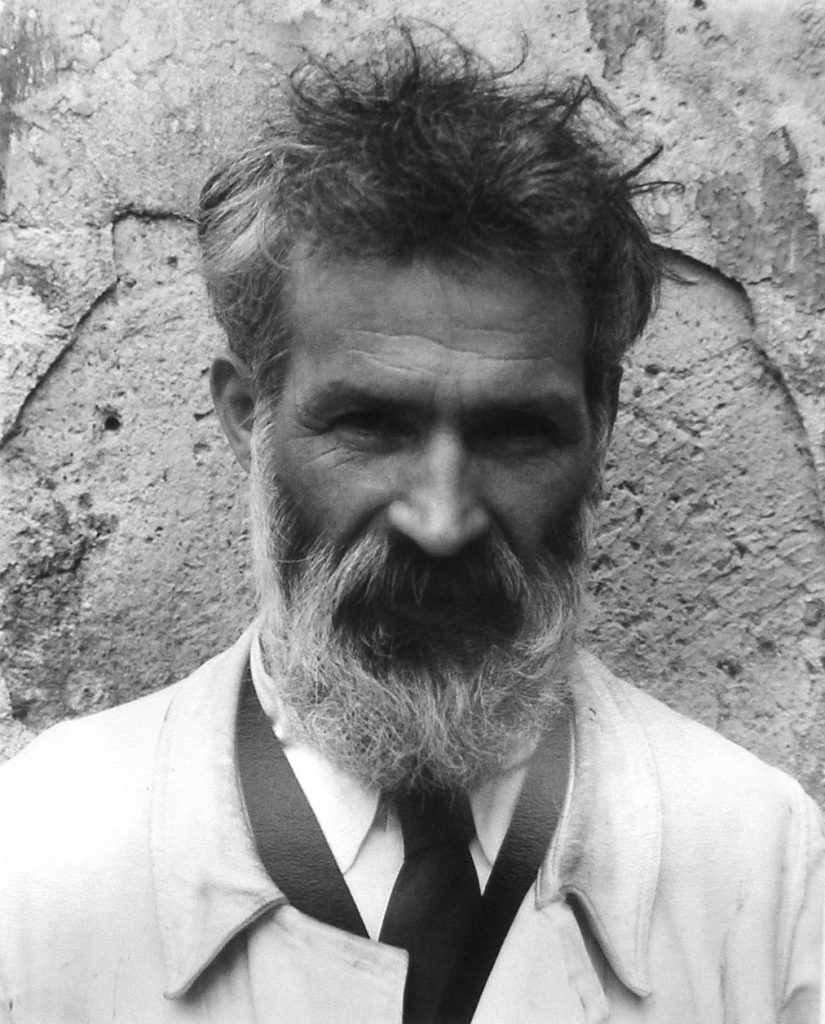

Brâncuși was an icon in the neighborhood. He typically dressed in peasant clothes—white linen pants and a loose tunic. And he kept a bushy beard, used a rough-hewn walking stick, and supposedly relished his reputation as a real-life Romanian rustic settled among the Parisian avant-garde.

If accounts by his contemporaries are to be believed, Brâncuși’s Oltenian habits went beyond his clothes, love of plum wine, and generous hospitality. Most of his time was spent in his barn-like studio and living quarters, whitewashed to the color of clouds, where he slowly refined his figures and built up strange arrays in the corners: an unfinished log was a base and a proclamation, standing next to a poured plaster cast and a wooden beam that could have been a house rafter. For decades, he puttered and moved things and covered them with tarps and took pictures that were fuzzy, with obvious dust on the camera lens. In his will, he declared that his studio should be made into a museum, and he left it to the French government. His daily life of work and struggle in the studio was his greatest artistic achievement.

Biographers say Brâncuși hated biography. His friend Peter Neagoe wrote a novel based on the sculptor’s life called The Saint of Montparnasse, and reportedly Brâncuși hated it. The book imagines the scene when Brâncuși creates “The Wisdom of the Earth.” He has been stewing in his studio for weeks, thinking about how to push art forward, beyond the things that we see—how to arrive at the form that is beyond form. Neagoe writes,

The day came when Constantin completed chipping out the squatting figure that he called “Wisdom.” He had meant to make it powerful and he deliberately made it crude. … The eyes of the figure were slits, the cheeks were flattened, the arms were held together under the breasts in a parallel position, giving it a block-like form. … “Humility is the beginning of wisdom,” and he called it “Wisdom,” because it humbly pointed the way to the future of art.

It may have been the future of art, but Brâncuși himself apparently did not think much of the piece and considered it a first experiment, a step toward the thing that he was destined to create, rather than an important work in its own right. Like most artists, nothing was ever finished for him. It could always be refined, reattempted, rearranged.

The government-led “C.P. campaign,” as it’s being called in the Romanian press, to purchase “Wisdom” has a website filled with photographs of actors, artists, and politicians who support the cause and are asking for donations. The “Wisdom” figure greets you with these words: Brâncuși e al meu. Eu donez (Brâncuși is mine. I donated).

But it’s not exactly mine as we understand the term in English. The al marks that the possession is closer to being “to” someone or inclined toward them rather than irrevocably being their object. The sentence could also be translated as “Brâncuși is for me.” Both meanings are correct.

The main gist of the website is that C.P. is a work of not only national but global importance because Brâncuși is one of the founders of modern art and the sculpture one of its most beautiful examples. The work belongs to the Romanian people, they argue, who should preserve the legacy of this important piece of art.

Brâncuși’s opaque description of the piece—he was not known for his literary talents—is reproduced on the website:

Cumințenia Pământului was my attempt to reach the bottom of the ocean with my index finger (the attempt to reach the ancient, the archaic). Because I got too scared when I lifted her veil. … The woman should never be unveiled. … Isis must remain covered under at least one of the seven veils of her beauty. The one of mystery—which gives her both her worth and her immortality. Cumințenia Pământului was for me that which is deeper in womanhood, beyond your psychology.

The site also tells us parts of the complicated story that brought “Wisdom” to her current embattled state. Her travels are difficult to unravel, almost magical—even a Brâncuși scholar couldn’t answer some of my questions about her. We learn that C.P. was created by Brâncuși in Paris in 1907 and then bought by Gheorghe Romascu, a Romanian architect, in 1911. Somehow the sculpture left Paris and landed in Bucharest. In 1957, Romascu was arrested by the Communist Party, and the work was confiscated as a treasure of national significance; in another version of the story, the Communist Party asked Romascu to loan them the sculpture for a show of great Romanian art in the 1950s, and it was never returned. The details of this transfer—of how C.P. ended up in the Romanian National Museum of Art in the 1950s—are obscure, but we do know that she was owned by the communist government of Romania and that she sat for decades in a prominent place in the Bucharest museum as an exemplar of the nation’s unique genius. In 2008, Romascu’s heirs successfully won a lengthy court battle for its return to their possession—but it has remained on display in the city.

In 2014, Romascu’s elderly daughter declared her intention to sell C.P., and she started the bidding at 20 million euros. (It has been valued at about 30 million euros by a Romanian tribunal.) The Romanian government asked for a chance to raise the money. The C.P. campaign was born.

Since the revolutions across Eastern Europe in 1989, questions of ownership and restitution in post-socialist states have been complicated and almost unsolvable. The Romanian communist state’s policies of nationalization, which were first enacted in the 1950s, meant that housing, land, and works of art were redistributed in the name of national well-being and greater equality. The beneficiaries were often elite officials being rewarded for their deep loyalty to the communist regime and their participation in its brutality. Other policies granted homes to marginalized groups, like the Roma, with few resources. But this was a mixed blessing. A Roma family, for instance, had to settle and live in that house, which meant giving up their much-prized mobility and staying in one place.

The fate of “Wisdom” is part of a bigger story about how unforgiving history can be. Who owns the flats, paintings, and plots of land in Romania now? And what if religious and ethnic persecution still plays out through housing and property? Without the protection of specific national policies, for instance, Roma families find themselves easily evicted from flats where they have lived for decades, and other landlords are reluctant to take them on.

And as tribunals and restitution cases across Eastern Europe have demonstrated over and over again, the question of what exactly is remedied when someone succeeds in getting a cash payout for the historical loss of property or life is difficult to answer. As important as they are, and I support reparations of all kinds, such settlements are unlikely to reduce trauma. Do they make things “right”? Or do they shed uncomfortable light on the fact that there is no such thing as an apology after tyranny?

Like most of these cases, the C.P. campaign has no outcome that is easy to support. The statue has stood for so long in the collection of the National Museum of Art in Bucharest that it seems almost vindictive to remove her. Sometimes I think, “Why bother? Just let ‘Wisdom’ rest. She looks like she could really use a nap.”

But maybe there is anger behind the family’s claim to “Wisdom,” and maybe it is justified and needs to be named. Romascu, the original owner, was detained and jailed, and his daughter wants justice. Many believe that the arrest and execution of Nicolae Ceaușescu, the Romanian military dictator from 1965 until his death, happened so quickly in December 1989—over the course of about one week—so that he could not name names and give details about members of his government, particularly the secret police, or Securitate, who did his bidding. Those were the men who would quietly slip back into positions of power and plunder the national resources that were privatized in the early 1990s. Perhaps the descendants of Romascu, and others like them, are simply trying to prove a point to all those who have profited from the repression of their ancestors and other countrymen since the late 1940s: We know what you did.

But in the case of C.P., it could also be about the money. The most recently sold Brâncuși work, an unfinished plaster study for “The Kiss,” sold for 5.4 million euros in 2014 at Christie’s auction house in New York City. “Wisdom” will sell, and for a great deal of cash. And that makes the whole debate seem almost crass. Romascu did not create the work—he bought it. So what is the family’s real connection to the sculpture? Why should they profit? And who has the right to own art of global significance anyway?

That day in Bucharest when I explained C.P. to my son, I was so oddly sure that she belonged in Romania. It’s a compelling narrative: a fight for the cultural rights of a poor country that is often exploited by wealthier, more powerful interests. But now I wonder: Do the Romanian people really have a right to this work when it was stolen through force or treachery? Is it a work of national importance? And when is a work of art bigger than a nation?

During Brâncuși’s lifetime, Romanians preferred ornate, religiously themed art modeled on that of the Western masters, so his works, including “Wisdom,” were often ridiculed in his country of origin. Though he became a French citizen in 1952, he certainly was not “French,” but he was not “Romanian” either. He became a man without a country. If we take him at his word, we might let his studio—that kaleidoscope of essential forms and domestic comfort—be his real masterpiece and cast “Wisdom” into the ocean, where it might come to rest in the place Brâncuși hoped to touch with his index finger.

We can view the C.P. campaign as a well-intentioned but ultimately overreaching attempt to claim an artist and a body of work as having some kind of national salience. Some brilliant studies in anthropology have shown how national identity, “Romanianness,” was consolidated under Ceaușescu’s regime and projected back onto a glorious past through art, literature, history, and philosophy. Maybe the celebrities and political figures behind the C.P. campaign are simply participating in a new, post-socialist production of nationalism, one that is more comfortable with a Romanian artist whose life was hybridized and polyglot. Perhaps it’s liminal figures like Brâncuși who have to be claimed for today’s Romania because they speak to historical cosmopolitanism and connection—and against widely held stereotypes of the region’s parochialism and standoffishness.

But for this to be true, the campaign would have to work. The deadline to raise 6 million euros was September 30, 2016. As of March 2017, the project had only raised about 1.2 million euros. The former prime minister of Romania, Dacian Cioloș, one of C.P.’s original spokespeople and great public champions, recently said he was naïve about how easy it would be to purchase “Wisdom” and keep her. As I edit this essay for publication, the fate of “Wisdom” is unclear. She has not been moved, but I imagine the sculpture will end up on the auction block unless something drastic changes.

Recently, I tell my son that so far it’s not clear what will happen to the statue we saw on the banner last summer. I know his world has changed when he says, “Well, maybe after they bought it, the government wouldn’t have any money left over. They should save their money.”

“Oh, okay. Why?” I ask. “What should they spend it on?”

“Um, probably toys. Like, for kids.”

I can’t exactly argue with that, but I wonder what my son has learned in the interim that makes him think it’s possible that a government can go broke and a work of art may not be worth saving. How much has he heard us say about the end of the arts and humanities national endowments? About what will happen if millions of people lose their health insurance? About how my husband will have to carry his passport anytime he travels, even within his own adopted country?

My husband tells me that although cumințenia is always translated “wisdom,” the word has other connotations, such as “self-assured calmness.” Maybe “Wisdom” is not only a postpartum new mother, tired and crouching. Maybe she’s facing down the 20th century; she can see past her descendants, and theirs, and she knows how much patience and resolve it will take to achieve the simplest thing: staying where she is, with dignity.

I miss that moment in the car on a hot day in Bucharest when my son and I felt so sure that “Wisdom” had a home and that we knew where it was. When it made sense for a poor country to give huge amounts of hard-earned money to buy a sculpture of a small, resolute woman with sagging breasts. When a small stone figure deserved a hangar-sized advertisement. The moment when it felt like Romania could be both ours and not ours. When there was an abundance around us, of imagination and belonging.

![Constantin Brancusi - The sculpture “Mademoiselle Pogany [I]” captures Brâncuşi’s sense of playfulness and sensuality.](https://www.sapiens.org/app/uploads/2017/07/03-Mlle-Pogany-Archives-of-American-Art-Wikimedia-Commons-792x1024.jpg)