The Cost of Cutting Anthropology Out of U.S. National Parks

IN FEBRUARY, ALONG WITH THOUSANDS of federal employees, I was fired without cause from my job as a cultural anthropologist with the U.S. National Park Service (NPS). Amid other agencies’ layoffs, my colleagues and I had held onto a naïve hope that because the National Park Service is a beloved public institution, the Trump administration might leave it alone.

But early one afternoon, my supervisor called a meeting to inform us that staff with probationary status (in the position for less than a year) would receive a termination letter by the end of the day. I received my letter within an hour. But I stayed at my desk until the last possible moment, documenting the status of the dozens of projects I was working on to assist colleagues who now had to take on my responsibilities.

In termination letters across the agency, the government claimed that terminated staff’s “subject matter knowledge, skills, and abilities do not meet the Department [of the Interior]’s current needs.” This claim was made without evidence of any effort to evaluate the value of our roles or performance. Thankfully, almost exactly a month later, a court issued an injunction against the firings, leading to the reinstatement of the dismissed staff in many—though not all—agencies.

Yet the damage was done.

Some of us, including myself, had already moved on to new places and positions, unable to wait on the hope of reinstatement. Many who had been spared from the initial firings saw the writing on the wall and accepted the next round of deferred resignations. According to the National Parks Conservation Association, the National Park Service has lost 24 percent of permanent staff since Inauguration Day, January 20, 2025.

My story is not unique. I have a long list of worries over the consequences of this staffing crisis—but I’m particularly concerned about the fate of anthropology and the projects it supports.

Between 2019 and 2025, I witnessed a gradual uptick in the number and distribution of cultural anthropologists across the National Park Service. Beyond the regional offices, more positions opened at individual parks. I was able to move from a contract position with a regional office to a formal NPS staff role when a cultural anthropologist position opened at Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado for the first time in 2022. The NPS also sought professionals with a background in anthropology for Tribal liaison and superintendent roles, among others. Regardless of the job title, there seemed to be a growing acknowledgment that cultural anthropologists breathe life into the heritage preservation work of the National Park Service.

When I lost my job, I was in my first year serving as the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) coordinator for the Southeast Regional Office of the National Park Service in Florida. Historically, those with NAGPRA responsibilities often defined which material was eligible for repatriation based on their own understanding of other people’s cultures and without meaningfully consulting Tribal leadership or descendants. As a result, there are still many ancestors’ and cultural belongings awaiting repatriation across the country.

The NPS hired me to correct course partly because I am a cultural anthropologist. I brought to the position not a claimed expertise in Indigenous cultures, but the desire to expand the views of decision-makers on repatriation by advocating for the expertise of the people actively living their culture. My intention was to build a program that respected Tribal sovereignty and recognized that the knowledge needed to complete the repatriation process is held within Tribal Nations. In the context of the NPS, these goals were cut short for me.

Others have taken up the mantle. However, it is not clear which positions will survive further reductions to staffing within the federal government—a threat that continues to loom over those still working for the NPS.

FRESH OUT OF graduate school, I began working for the NPS in 2019, full to the brim with research toolkits and flashcards on anthropological theory. As I moved through my early career as an anthropologist—from intern to contractor to seasonal employee and finally into a permanent position—I often found myself examining what it meant to be an anthropologist outside of academia.

National Park units are organized into geographic regions, and in this structure, a small number of subject matter experts provide technical assistance across a region. Most anthropologists in the NPS work at the regional level. A handful of parks have an in-house anthropologist on staff. But in either setting, the central goal is to identify communities with traditional associations to park lands and to document the resources these communities find meaningful to their cultural identities. These include resources such as structures, objects, plant species, ecosystems, landscape features, and celestial bodies, among others. (The NPS calls these “ethnographic resources.”)

My first few years were spent working for a regional office reviewing earlier research to identify these ethnographic resources, document the history of their uses, and create a record of how they have been managed. I could sometimes get quite disheartened that I wasn’t in the field conducting research. I wasn’t entirely convinced that I could call myself an anthropologist. But after studying dozens of these reports, documenting over 1,000 ethnographic resources, and a bit of self-reflection, a picture of what I was helping to accomplish began to emerge.

The National Park Service does so much more behind the scenes than visitors and park lovers will ever witness.

The best term I’ve found to describe an NPS anthropologist is “culture broker,” coined by anthropologist Richard Kurin to describe the practice of anthropologists as mediators of culture to the public. What NPS anthropologists provide—and where there’s real need—is the ability to recognize the crossroads and overlaps between what the Park Service hopes to accomplish and the traditions and lifeways of communities who will be affected by their actions. When these roads conflict, an anthropologist can serve as a broker between the needs and responsibilities of both parties. They can also see and advocate for the ways each can help the other.

Prior to my work as a NAGPRA coordinator, I held an anthropologist position at Rocky Mountain National Park. In that role, I was able to share information about ethnographic resources with natural resource managers and administrators at the park. Together, we strategized how we might utilize management techniques already established to increase Tribal access to traditional homelands and resources. I also led ethnobotany training for seasonal biologists and foresters. We referred to the broad categories of plant information previously shared by Tribal representatives, comparing and contrasting the kinds of plant knowledge park staff would have learned in a Western academic setting to what Indigenous people often learn from elders and tradition bearers. In other words, my job was to translate culture across the silos of professional fields.

The National Park Service must maintain an anthropological perspective to account for the diverse ways people relate to the places now under their care. This is especially important considering the many historic and violent acts of removal of Indigenous peoples that allowed for the establishment of most park units.

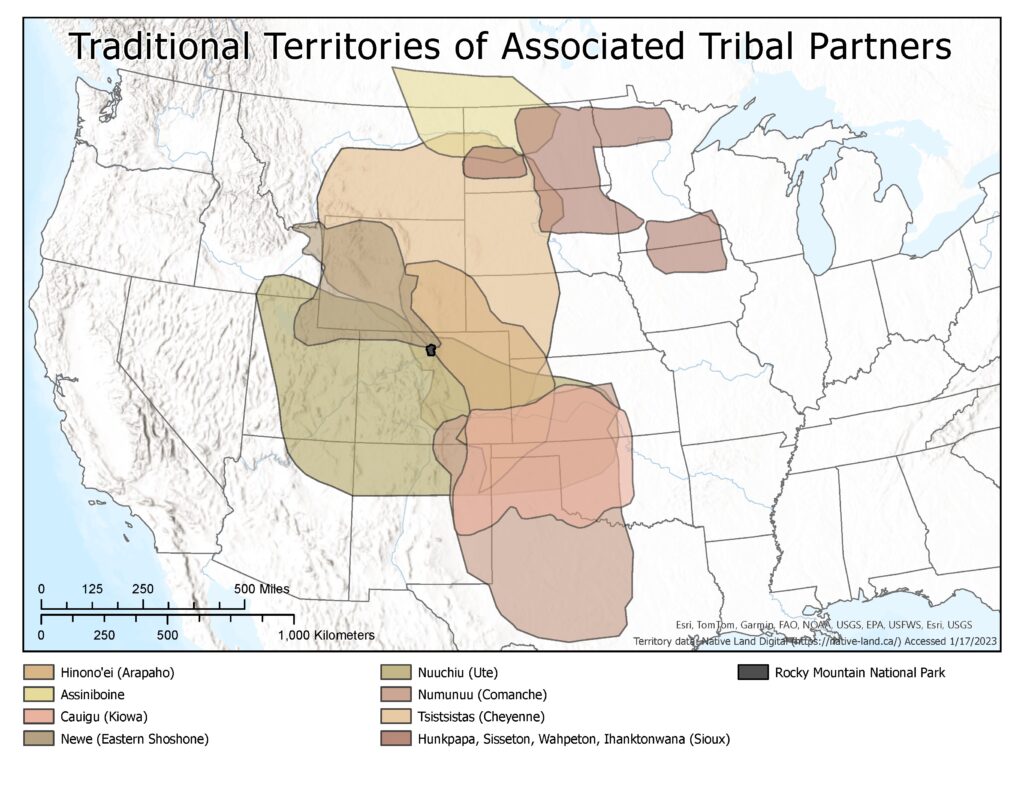

At Rocky Mountain, for example, many of the landmarks within the park bear Indigenous names. But these place names were “officially” designated by a local cartographic organization a generation after political violence led to the relocation of the Ute, Arapaho, Cheyenne, Eastern Shoshone, and others who lived in what is today the park to distant reservations.

Today, 10 Tribes with ancestral territory in parts or the whole of the park reside on reservations 5–12 hours away by car. On the surface, this forced distance can make it appear that the connections between people and place are something that only existed in the past. But in talking with people from these communities and asking questions about the places, stories and natural beings they value, park staff have learned that there is not an inherent distinction between past and present. The importance of the land now within the park continues to be upheld as a place in which Tribal ancestors walked and lived, regardless of whether their descendants have been to the park.

IN THE AFTERMATH of the 2025 firings, many professional associations spoke up in support of colleagues affected by layoffs and funding cuts, including the Society for American Archaeology, the American Alliance of Museums, and the Society for American Archivists, which all published statements of advocacy.

I was disappointed that no such statement of support came out of the American Anthropological Association or Society for Applied Anthropology, though perhaps not all that surprised. Though cultural anthropology job openings have been on the rise, I also saw the infrequency with which they were advertised compared to archeologist and historic preservationist jobs. This makes me feel that there’s a general lack of awareness, within and outside of the NPS, about the importance of cultural anthropology to land stewardship.

Perhaps this is due to limited exposure. It wasn’t until the 1980s that the NPS established a cultural anthropology program. Until that time, archaeology had been the sole subfield of anthropology practiced by NPS staff since the 1930s. At first, NPS cultural anthropologists were called ethnographers, people who study culture through observation and interviews. This title was applied to avoid confusion with archaeologists, who then held the title of “Anthropologist.” Today the two programs are differentiated as archaeology and cultural anthropology.

In the end, the NPS’ ability to fulfill its cultural preservation responsibilities is undermined when the contributions of cultural anthropologists are undervalued. Take, for example, that in the jargon of federal preservation work, the NPS categorizes historic buildings, archaeological sites, and museum objects as cultural resources rather than strictly historical. In that nomenclature, some recognition exists that these places and materials are important to the contemporary identities of people and communities. Cultural anthropology offers one means of understanding the preservation concerns of those communities.

Recent headlines on NPS budget cuts have primarily focused on tourism, which makes sense given that many non-Native visitors value and experience national parks through recreation. Strategically, it is easier to galvanize public concern around issues like long lines, dirty facilities, and reduced services—problems that directly affect millions of annual visitors.

The trouble is that the NPS does so much more behind the scenes than visitors and park lovers will ever witness—or know to fight for. NPS anthropologists are just one of many professional groups hurt by changes at the federal level. But I hope their importance is recognized. Their insights should be used to support connections between people and the places the National Park Service stewards—and in the future, inform (re)building its programs.