Listening to Murmurs

1

The shared taxi meanders through Tsaar—

resting abode of Nund’e Resh,

the mystic poet who proclaimed

[1]

[1]

Tsaar (also Tsrar, Charar, Charar e Sharief) is the resting abode of Kashmir’s revered mystic poet Shaykh Noor ud din, affectionately also known as Nund’e Resh (or Nund Rishi). Out of reverence, he is honored with titles such as Shaykh al Alam (spiritual guide of the world) or Alamdar e Kashmir (flag bearer of Kashmir).

dying before death

[2]

[2]

In mystical traditions, dying before death, a radical reimagination of death, refers to a transformative process—a seeking—to purify oneself and realign one’s consciousness toward a profound sense of being. See Abir Bazaz’s book Nund Rishi: Poetry and Politics in Medieval Kashmir.

By the window seat,

I listen to endless landscapes fleeting past me

red poppy flowers amid blades of grass

murmur against

a bleak garrison—

break the landscape

broken land

blooming

gulaal

[3]

[3]

In Kaeshur (or Kashmiri), poppy flower is called gulaal.

—flowers of the wasteland

poppy seeds can stay dormant for decades without blooming

upon disruption of the soil, fugitive poppies

suddenly shoot up

a hitherto unknown force

surging forth

As the taxi moves along the errant path

marked with the mystic’s verses

across walls and boards,

my gaze drifts to the partly erased graffiti

[ ] is alive in our hearts

the taxi stereo blares

mohabbat ki keemat ada hum karenge—

“we shall pay the price of love”

sung by Attaullah Khan Esakhelvi

whose songs on cassette tapes

—unrequited love and longing—

echoed tea stalls, buses, and autorickshaws in the nineties

as prison guards broke our erring bodies

2

Close to the mystic’s resting abode,

a potter’s hands aid a quiet revolution

his wheel hums

as he shapes delicate vessels from clay,

sculpting their holding capacity

swaying his head rhythmically to the wheel’s murmur and the kalaam on the radio

[4]

[4]

Kalaam means speech or discourse and also refers to a poet’s literary works or a particular piece of poetry or its musical rendition(s).

tender forms emerge

whirling against the frangibility of their own beings

“Ye chu sir-e-khoda”—

“it is divine secret,”

the potter tells me:

“a laborious process,

sincere work

bearing divine’s grace

the earth carries multitudinous veins,

we work with one of them

there are different forms of clay—

fourteen, in the nearby hill alone

we know each of these veins intimately—

clay that holds and the one that falls apart”

3

Peering into the clay vessel’s void,

I gather Nund’e Resh’s words:

ژالُن چُھی وُزملہٕ تہٕ ترٛٹے

ژالُن چھُی منٛد نٮ۪ن گٹہ کار

ژالُن چھُی پربتس کرُن اٹے

ژالُن چھُی منٛز اتھس ہیوٚن نار

ژالُن چھُی پان کڈُن گرٛٹے

ژالُن چھُی کھینٚۍ یکہ وٹہ زہرخار

[5]

[5]

G.N. Adfar, Alchemy of Light, Volume II (G.N. Adfar, Quaf Printers, 2013), 323. Translation mine. See also Abu Nayeem, Noor Nama: Kulliyat e Shaykh al-Alam (Sheikh Mohammad Usman and Sons Tajran’e e Kutub, 2006), 20.

“Endurance is lightning and thunder

Endurance is darkness at noon

Endurance is lugging a mountain on one’s back

Endurance is cradling fire in one’s palm

Endurance is being milled to nothing

Endurance is gulping heaps of poison all at once”

[6]

[6]

The last line is rendered differently in some versions, which could be translated as “endurance is swallowing poison (veh) and pain (gar),” and gar bears the double meaning of both pain and poison. See Moti Lal Saqi, Kulliyat-e Shaykh al-Alam, 35.

4

As we walk through Tsaar, M. recalls

the siege of 1995,

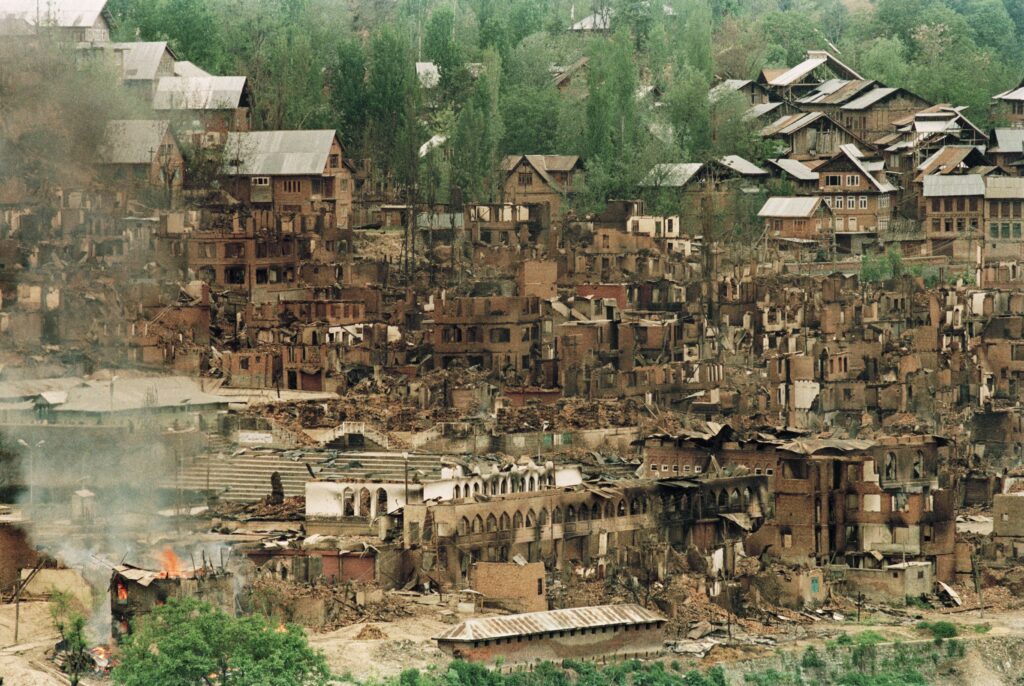

[7]

[7]

Following a monthslong siege and a standoff between tens of thousands of Indian troops and militants—about 150, according to The New York Times, or 70, according to The Washington Post—Shaykh Noor ud din’s mausoleum and the adjoining mosque, a 15th-century wooden structure, went up in flames on May 11, 1995. More than 1,000 homes and hundreds of shops were destroyed in Tsaar. According to The Washington Post, two explosions at 2:00 a.m. on May 11 ignited the fires, and on May 12, when the army brought in Indian and foreign journalists, locals accused the army of destroying the town—including the mosque and the mausoleum—using gunpowder and mortars. By 1995, the army setting fire to entire neighborhoods had become a common technique of terror. See Shiraz Sidhva, “Kashmir Peace Hopes Go Up in Smoke,” Financial Times, May 15, 1995. The mosque and the shrine were later rebuilt.

a sea of people leaving

Thousands of homes,

mystic-poet’s shrine, and its adjacent mosque—

entire neighborhoods

going up in flames

Dwellers returning to ruins and corpses

grief’s gnawing teeth

Sounds of mourning and protest echoing

Tsaar—

ghost town

archive of debris,

gunpowder, mortar—

veins of the earth, now acrid

sir e khoda, wounded

abode of lost homes

present continuous

present perfect continuous

As the day departs,

M. invites me to her friend’s wedding nearby

fragile moonlight enshrouds Tsaar

the smoke of isband lingers in the air—

[8]

[8]

Peganum harmala, or wild rue, is burned on special occasions in Kashmir.

it is the night of henna

women gather in a circle and begin clapping

gently at first

each summoning a fragment,

swaying their bodies—

I listen to murmurings

rising over the racket of History

until History is inaudible

fragment after fragment, the women suture a song

elegizing

the loss of community

and compassion

that, as they say,

marked the burning of Tsaar:

“They burnt down Tsaar, obliterating it to smithereens

Laying bare our wounds, forever to bear

They burnt down Tsaar, obliterating it to smithereens

We witnessed, right in front of us, how it was set ablaze

They burnt down Tsaar, obliterating it to smithereens

We committed everything to our memory

They burnt down Tsaar, obliterating it to smithereens

We took note of the perpetrators

They burnt down Tsaar, obliterating it to smithereens

That togetherness, we lost forever …”

5

As I walk inside the mosque next to the mystic’s masoleum,

a wayfarer entrusts me with a mound of amorphous clay

and disappears, his mutterings trailing behind him

6

With a flick of the kraal’e pann

[9]

[9]

A potter’s string used to separate or cut off a finished vessel from the wheel.

the potter severs the vessel from the turning wheel,

gently resting the form on the ground

Clay vessel’s being still resonant with the wheel’s gyrations

“Dopmai na ye chu sir e khoda?” the potter murmurs—

“Didn’t I say it is a divine secret?”