How Archaeologists Uncover History With Trees

In the fall of 1282, a young carpenter went to his favorite stand of juniper trees in southwestern Colorado. That stand contained a large number of tall trees that could be fashioned into construction beams, but it also had spiritual significance as part of a sacred landscape. After saying a prayer, he got to work.

His stone ax was made of a river cobble that he had painstakingly shaped into an ax head and, with a bit of pine pitch, hafted to a wooden handle of bent willow branches and sinew. Once he found a straight juniper he liked, he pummeled its base, chopping through bark and wood layers with blow after blow. Eventually, he was able to safely push the tree over onto the ground. After taking a short rest, sipping water from his ceramic jug and snacking on pinyon nuts and deer jerky, he used his trusty ax to remove the branches and bark along the length of the tree, thus creating a straight construction beam.

The next day, he enlisted a group of friends to carry the beam a short distance to the cliff dwelling he wanted to repair. (Unlike his ancestors, who had lived in pithouses on the mesa tops, his people built their homes as large apartment buildings in beautiful, massive, natural rockshelters below the mesa tops—probably for defensive reasons.) The young man and his friends used the beam to shore up the roof of the room they used for ceremonies. They had built the room in the late 1270s, but it needed repair. Once they returned it to good working order, they continued to use it for a few more years, but they were the last holdouts in a sparsely populated region. Finally, they too left for points south, just as the rest of the population had done several years earlier.

This region of the Southwest, which had been populated by as many as 30,000 people at one time, lay empty. Its residents had abandoned it—or had they?

Because of dendrochronology, or the study of “tree time,” we know when the young lumberjack cut down the juniper and when he and his construction-worker friends repaired what archaeologists now call Kiva D at Spring House in present-day Mesa Verde National Park. And as a result of nearly a century of collaboration between archaeologists and dendrochronologists, there are now 4,348 tree-ring dates available from 143 sites at Mesa Verde. We definitively know that most of the cliff dwellings were built and used in the 13th century.

And when we look at the tree-ring dates decade by decade, some intriguing patterns emerge. There are 284 tree-ring dates from the 1270s, indicating that construction and repair activities were in full force at a dozen cliff dwellings within the region that now comprises the park. In stark contrast, however, there are only five tree-ring dates from the 1280s, indicating that construction and repair activities were almost nonexistent at Mesa Verde during that decade. They occurred at only four cliff dwellings—one of which was Spring House.

Archaeology is a wonderfully rich multidisciplinary science that benefits greatly from dendrochronology. But it is also anthropology. From the stunning precision of tree-ring dates to the rich tapestry of Native American oral history, we know in astonishing detail much of what happened—and when, where, and why it happened—at Mesa Verde.

Questions about the Mesa Verde region’s early inhabitants, known as Ancestral Puebloans, have captured the attention of the general public and scientists alike since the cliff dwellings were “discovered” by cowboys Richard Wetherill and Charles Mason on December 18, 1888. Why did the Ancestral Puebloans leave their carefully constructed cliff dwellings? Where did they go? Was the area completely abandoned or later used again?

In the December 1929 issue of The National Geographic Magazine, astronomer Andrew Ellicott Douglass of the University of Arizona published the first tree-ring dates for Mesa Verde. (Why, you ask, was an astronomer studying tree rings? He studied trees while trying to find a land-based record of the 11-year sunspot cycle.)

As part of his study, Douglass defined the “great drought,” a 24-year period of severe drought recorded in tree rings from 1275 to 1299—a span that included some of the driest years in the 2,000 years represented in his tree-ring record. Douglass suggested in 1929 that the great drought might have been responsible for the Native American “abandonment” of Mesa Verde.

Douglass’ idea remains exceedingly popular with scientists and the general public because it is commonsensical. But it borders on climatic determinism, wherein social and cultural development is determined by fluctuations in local climate. It suggests that resourceful and ingenious people who lived in the Mesa Verde region for millennia suddenly lacked the ability to cope with drought.

By combining archaeological and tree-ring data with insights drawn from Native American oral traditions, linguistics, genetics, and other data, we now know where the people who lived at Mesa Verde went during the late 13th century: Many moved south and east to the Rio Grande Valley near present-day Santa Fe and Albuquerque in New Mexico. Although they did so in part because of the great drought, it is also clear that existing social, political, and religious challenges created “push” factors that induced them to leave. In addition, social, political, and religious factors “pulled” them to new areas in the Rio Grande Valley and elsewhere in the American Southwest.

We also know that Mesa Verde was never truly “abandoned.” While it is true that people stopped building and repairing cliff dwellings there after 1282, Mesa Verde remained a rich cultural landscape for Ancestral Puebloan tribes seeking natural resources and spiritual renewal.

Many Americans are less attuned to the notion of sacred landscapes. People often think undeveloped landscapes are “empty” until visibly modified by humans. They assume that because Native Americans chose not to live at Mesa Verde after the 1280s they had, by definition, abandoned the region. Nothing could be further from the truth: Numerous Native American tribes have maintained an active spiritual and cultural connection to Mesa Verde, though they are now scattered throughout other parts of the Southwest.

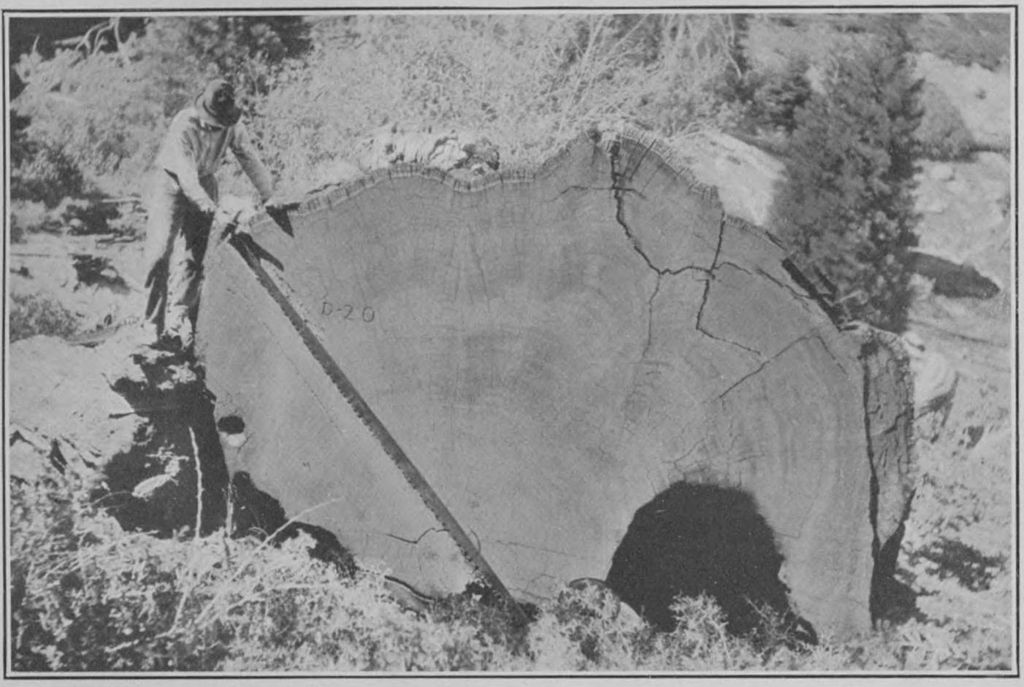

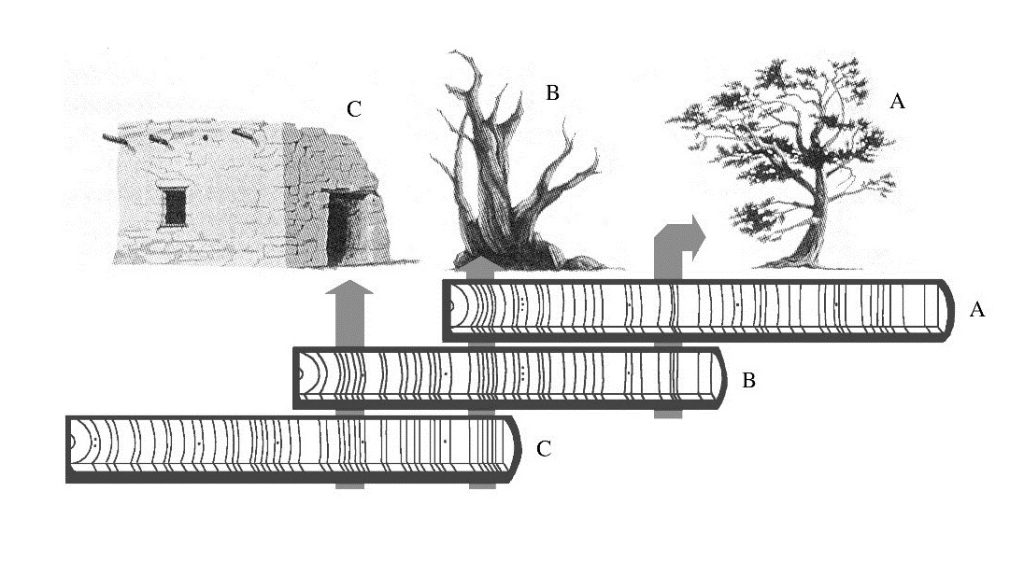

The precision of dendrochronology has been critical to answering some of the long-standing questions that surround Mesa Verde and the history of its peoples. The basic principle of tree-ring dating—and what makes it so accurate—is crossdating, in which the dendrochronologist matches ring patterns from living tree to living tree, then from one tree stand to another, and then out across the landscape until regional tree-growth patterns are well-understood. Once that task is accomplished, the dendrochronologist works back in time to crossdate successively older specimens, first analyzing samples from dead trees and then specimens from archaeological contexts.

In principle, crossdating is simple. In practice, it can be astonishingly difficult. In contrast to popular (mis)conceptions, tree-ring dating is not performed by simply counting rings. If it was, our ring count would be off by one year for each and every extreme drought year, when trees don’t grow—and therefore don’t create any ring. And there are lots of drought years in the Mesa Verde region!

Now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Mesa Verde National Park is home to more than 4,500 documented archaeological sites spanning more than 1,000 years of continuous, and occasionally dense, human occupation. It is undeniably one of the richest archaeological regions in the world, and it is a sacred place for many—not just Native Americans but anyone who can appreciate the preservation of world heritage.