Two Pioneering Female Archaeologists

Precocious. Prolific. Audacious. Magnanimous. Each of these terms describes archaeologist Hannah Marie Wormington and her protégé Cynthia Irwin-Williams. [1] [1] Editor’s note: Portions of this essay have been drawn from the author’s chapter in The Great Archaeologists and his entry on Worthington in the Colorado Encyclopedia. As pioneering female archaeologists in an arena dominated by Euro-American men, they created scholarly niches on the frontiers of their field. Acerbic and cavalier, they were larger-than-life figures whose impact reverberated far beyond their peer-reviewed publications.

Separated by a generation, both were born in Denver, Colorado. Their lives and careers overlapped beginning in 1950, when 14-year-old Cynthia Irwin began volunteering for Wormington at the Denver Museum of Natural History (DMNH; now Denver Museum of Nature & Science, where I work).

Over the next four decades, these women played significant leadership roles in the development of North American archaeological method and theory, becoming the first and second women to be elected president of the Society for American Archaeology. At the same time, they mentored hundreds of young archaeologists and helped create a more equal and supportive environment for subsequent generations. Despite their contributions, their stories are not widely known.

Hannah Marie Wormington

One of the first female archaeologists in North America, Wormington was born in 1914 to a French mother who taught her the language—a skill that proved useful in her career. At the University of Denver, Wormington was inspired to study anthropology by one of her teachers, French archaeologist E.B. Renaud.

At 20, after earning her bachelor’s degree, she and her mother embarked on a European tour. Thanks to Renaud’s connections and her own French fluency and initiative, Wormington helped excavate a Paleolithic site in France and met luminaries such as archaeologist Dorothy Garrod. Later that year, the Colorado Museum of Natural History hired her as an assistant in archaeology to catalog donated stone tool collections, for there were no other professional archaeologists on staff at that time.

In 1937, she enrolled in graduate school in anthropology at Radcliffe College. Given the economic challenges of the Great Depression and the travel restrictions of World War II, Wormington did not earn her master’s degree until 1950.

She then became the second woman admitted by Harvard University’s anthropology department. At the time, some professors didn’t allow women in class, so she had to sit outside some lecture halls. In 1954, she defended her Ph.D. dissertation on the Fremont culture, a loose-knit group of semi-sedentary agriculturalists who lived in what is today western Colorado and other western states more than 700 years ago.

Although she was the author of dozens of peer-reviewed publications, Wormington is best known for her textbooks, which, in her words, she “presented in a manner acceptable to the intelligent layman.” Ancient Man in North America, first published in 1939 when she was 24, served as the standard textbook on the subject for nearly four decades. Prehistoric Indians of the Southwest, first published in 1947, was nearly as popular. She published using her initials, H.M., to partially conceal her gender, as many female scholars did in an effort to be taken more seriously by the academic establishment.

Women dominated Wormington’s field crews at a time when many male archaeologists refused to allow women in their field camps in any capacity, much less leading and working on all aspects of the excavations. Those field expeditions explored archaeological questions ranging from the documentation of the earliest human occupation in North America to understanding the subsistence practices of early hunter-gatherers.

In the 1930s and 1940s, Wormington excavated rock shelters and other sites across western Colorado and eastern Utah, including the Turner-Look Site, to document the ancient history of these regions and to recover exhibition-quality specimens for DMNH.

In the 1950s, she searched western Alberta in an unsuccessful attempt to find the earliest human sites in North America, reasoning that they would be in the ice-free corridor that ran down the center of the continent during the last ice age. In the 1960s, she excavated the Frazier Site, a 10,000-year-old bison kill site in Colorado that allowed her to understand how Paleoindians killed, butchered, and utilized those magnificent beasts.

Wormington was a museum-based archaeologist who, while lacking direct access to students, nevertheless enjoyed great success in making archaeology accessible to the masses through exhibitions and popular writing. The western archaeological community referred to her Denver home as the “command center” and called her “the Queen.”

For decades, she served as a gatekeeper and broker of archaeological research on the earliest human occupations of the American West. As another of her protégés, C. Vance Haynes Jr., wrote in an obituary:

“Everyone took great pride in being a part of Marie’s world, and for every new find of every new season, we couldn’t wait to tell Marie. Her response was invariably enthusiastic and charged with encouragement. One always left Marie on a high note. Seldom did she disapprove of one’s actions, but if she did you knew about it right then and there.”

DMNH Director Alfred Bailey fired Wormington in 1968, after a longstanding feud came to a head. For a variety of reasons, Bailey felt Wormington had not been acting in the best interests of the museum, so he abolished the department of archaeology, of which she was the sole curator.

Wormington lived within a mile of the museum for the next 26 years. Given her status in the Denver community, the widely publicized split with Bailey and the museum proved toxic for decades. The museum finally granted her emerita status in 1988, recognizing her contributions two decades after her departure. She died tragically in a house fire in 1994, likely caused by her stray cigarette.

Cynthia Irwin-Williams

Born in 1936, Cynthia Irwin-Williams had chronic asthma as a child. While digging in the dirt wouldn’t seem like the wisest career choice, she was determined to overcome her ailment and pursue her passion for archaeology. Thanks in large part to Wormington, she succeeded. As a teenager, Irwin-Williams and her younger brother Henry excavated several sites in the Rocky Mountain foothills near Denver, under Wormington’s mentorship. Despite their young ages, DMNH published all their site reports.

Following Wormington’s lead, Irwin-Williams pursued degrees at Radcliffe, earning her bachelor’s in anthropology in 1957 and master’s in 1958. Also like Wormington, she wasn’t allowed inside some of the classrooms, and she participated in a Paleolithic excavation in France, where she was given menial tasks because she was a woman. She later said the experience motivated her to lead her own digs and to treat participants more fairly. Indeed, colleagues would eventually praise her for supporting her field crews as if they were family.

Irwin-Williams earned her Ph.D. in archaeology from Harvard in 1963 with a dissertation focused on the excavation of the Magic Mountain Site, an archaeological site with a 9,000-year human history located just west of Denver, which Wormington had arranged. (Michele Koons, another DMNS curator and also a Harvard graduate, led an award-winning re-excavation of the Magic Mountain site in 2017 and 2018, thus building on Wormington and Irwin-Williams’ success and legacies.)

Irwin-Williams’ employment followed a more traditional academic path than did her mentor’s. She worked at Eastern New Mexico University from 1964 to 1982 and in administrative and research positions at the Desert Research Institute in Reno, Nevada, from 1982 until 1990.

On the other hand, Irwin-Williams’ research was more geographically diverse and ambitious than Wormington’s. With George Agogino and Henry Irwin, she co-directed the Hell Gap Project (1961–1966) in Wyoming, where they demonstrated the chronological sequence of the earliest human occupations of the Great Plains through stratigraphic analysis.

In the early to mid-1970s, she attempted to study the sociopolitical organization of the people who built Salmon Ruins—a large, classic Ancestral Pueblo site in northern New Mexico occupied more than 800 years ago. In so doing, she helped pioneer the use of computers in archaeological analysis.

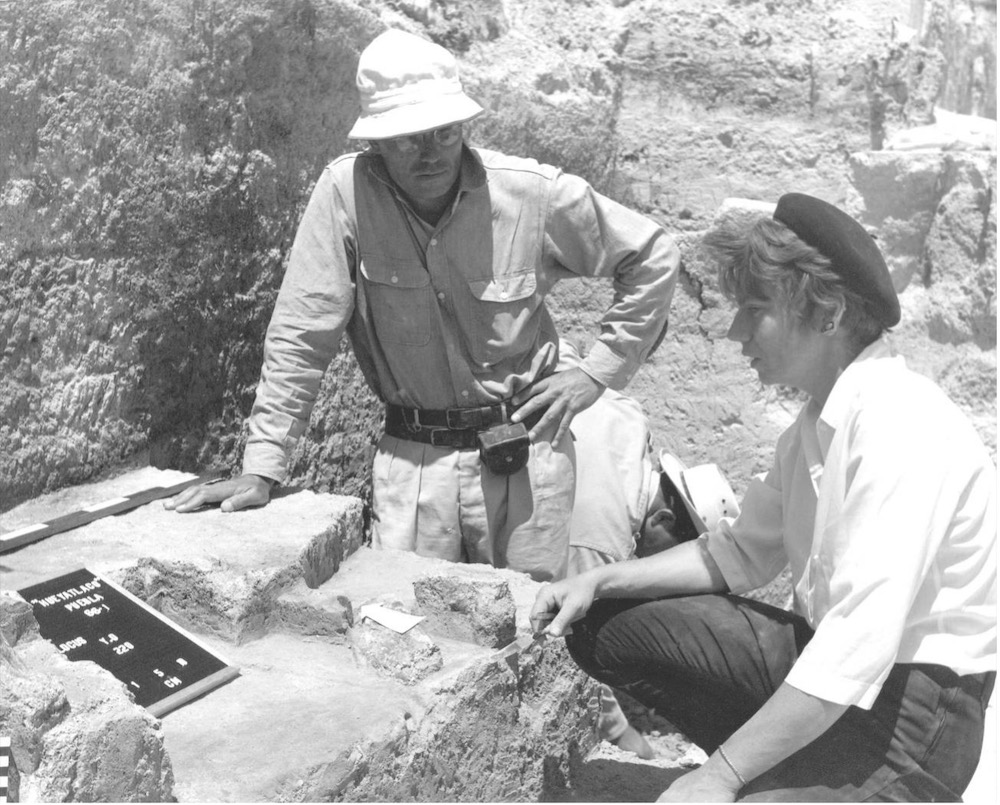

Early in her career, Irwin-Williams became embroiled in a scholarly controversy that overshadowed her other contributions. In 1962, she become a principal investigator in excavations of early human sites at Valsequillo Reservoir, near Puebla, Mexico. In 1969, she and her colleagues published results of an experimental dating technique, uranium series analysis, which suggested an unprecedented age of 250,000 years for the earliest artifact-bearing layers at the site.

Although Irwin-Williams’ name was listed on the publication, she argued for the rest of her career that the site was less than 20,000 years old. But the damage had been done.

Both Wormington and Irwin-Williams entered archaeology when men dominated the field. Today in the U.S., more women than men are awarded doctorates in archaeology. Yet there continue to be inequalities in the field, ranging from sexual harassment to fewer women being published in major journals to fewer senior scholars who are women receiving major grants. The struggle goes on.

Given their forceful personalities, dogged ambition, scholarly acumen, and fierce determination, both women individually deflected the discrimination they encountered, and both were undeniably successful. With nearly a century of combined archaeological activity between them, they set research, publication, service, and mentorship standards that few archaeologists have matched.

Both women were working on important manuscripts when they died. Irwin-Williams’ death in 1990 at the age of 54 left her Salmon Ruins monograph incomplete, though colleagues have since completed several books that build on her work.

Wormington’s death at age 79 left an 800-page magnum opus unpublished. In a sense, then, archaeologists today are continuing their unfinished work of a more inclusive and better archaeology.