What Do Monuments Reveal About Their Makers?

Twice a day, on my way to and from work at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science (DMNS), I walk through a magnificent, monumental stone gate that majestically spans the east entrance to City Park. Victoria Monti had the gate built in 1916 after the death of her husband, Joshua Monti, a Swiss immigrant to Colorado who made his fortune in the mining industry.

I’ve often wondered why Victoria wanted to memorialize Joshua in this way. The Montis are not entombed here; their remains are interred several miles away in an impressive mausoleum at Denver’s Fairmount Cemetery, where many other Colorado business leaders, politicians, and glitterati are buried. So why erect a gate? Did Victoria believe she was helping City Park and the museum? If so, how?

What did Victoria want to communicate about Joshua through this structure? The Monti gate can seem imposing and prohibitive. Even if the gate is never closed, such a monument can serve as a barrier to entry for people who don’t enjoy true freedom of movement in this country, for whatever reason. Was the gate meant as a barrier, subtly shutting out the riffraff? Or did Victoria simply want people to think of her husband as they passed through the threshold to a beautiful place?

Walking through the Monti gate reminds me of humankind’s need to be remembered, the lengths some people will go to achieve that end, and what messages they’re compelled to communicate through their memorials. China’s first emperor was buried with an estimated 8,000 terra-cotta soldiers—an army that trumpets a message of military might. In the 1600s, Mughal emperor Shah Jahān immortalized his wife through the Taj Mahal, an expression of love and romance rendered in architecture.

Denverites know very little about Victoria and Joshua Monti’s life story, in part because the only things written on their namesake gate are their names and its date of construction. The monument offers mute testimony to the couple’s philanthropic and civic interests.

So I’m inclined to compare the Monti gate with another massive stone monument that conveys a clearer and very different message.

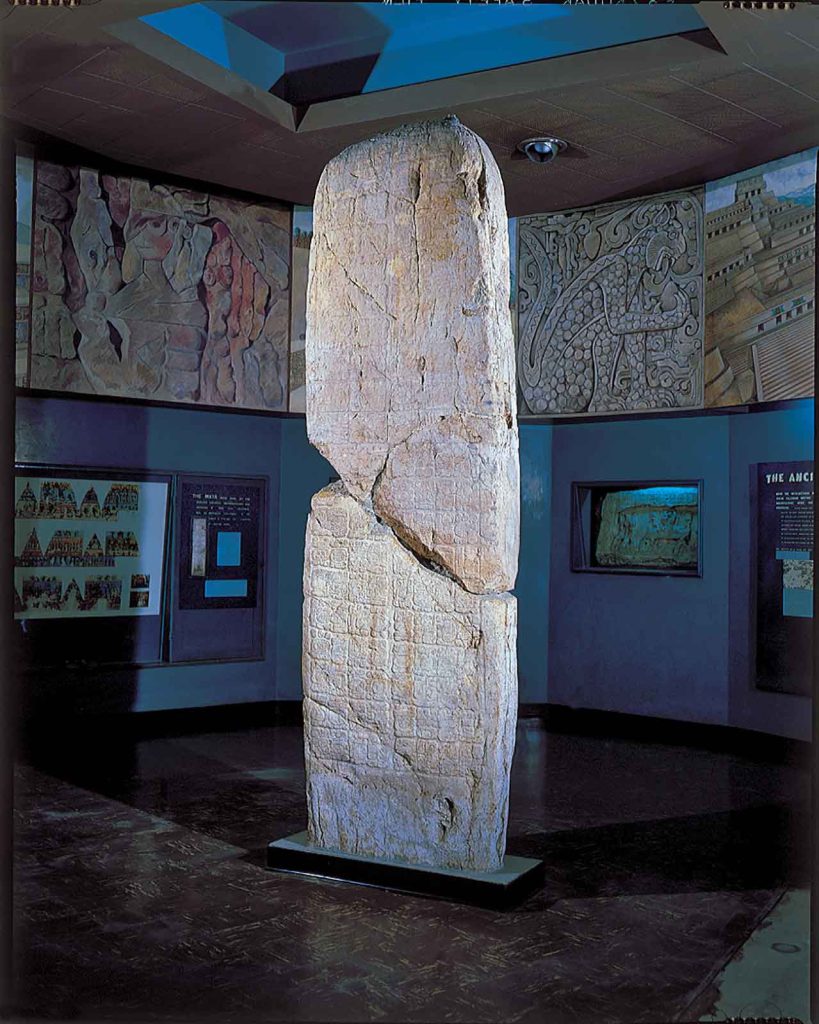

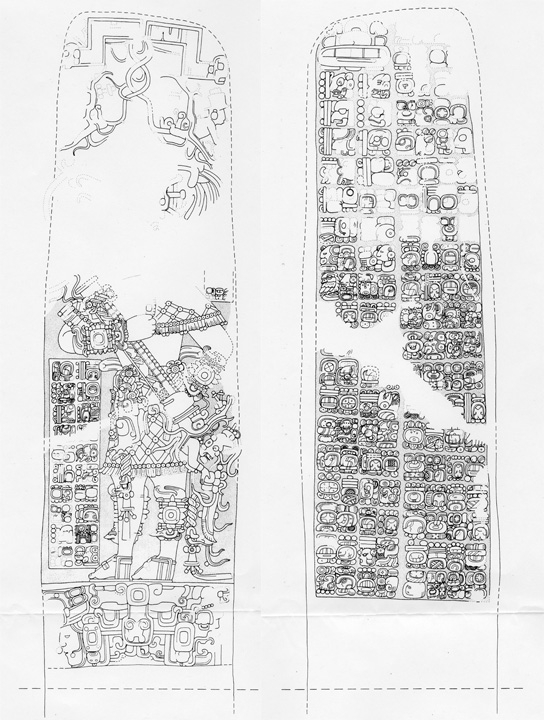

A limestone stela (“steel-ah”) in the archaeology collection at DMNS tells an epic tale. “Stela 3” hails from the ancient Maya site of Caracol in modern Belize. Carved into the weathered stone is an image of Lord K’an II, bedecked in royal finery and wielding a scepter in his right hand.

Lord K’an II was arguably the most successful ruler in Caracol’s history. During his reign from 618 to 658 (in the Common Era calendar; the Maya had their own calendrical system), Caracol’s influence stretched across much of what is now Belize and northern Guatemala.

In early 2014, epigrapher Marc Zender of Tulane University visited the museum and provided us with a provisional interpretation of the glyphs on Stela 3. (His unpublished notes are on file at DMNS.) According to Zender’s reading, Lord K’an II dedicated this monument to himself on January 25, 633, and the glyphs trace nearly 120 years of his royal lineage. The stela’s story aims to legitimize Lord K’an II’s reign by interweaving genealogy with mythology.

Again according to Zender’s reading, a woman named Lady Quetzal gave birth to a girl, Lady Batz’ Ek’, on April 23, 566. On September 7, 584, after she had turned 18, Lady Batz’ Ek’ traveled to Caracol to marry the king. She, in turn, gave birth to Lord K’an II, who acceded to the Caracol throne at the age of 29 or 30. The following year, a militaristic god—Three People Eater—arrived at Caracol to announce a renewed war against their archrival city-state, Naranjo, in what is now Guatemala. Note that Lord K’an II invokes religious power to justify the violence.

On March 19, 623, Lord K’an II led a massive celebration to honor a significant date on the Maya calendar, much like we celebrated the turn of the last millennium. In doing so, he demonstrated his full command of Caracol’s formidable political, secular, and military forces and resources.

The most significant event documented on Stela 3 is Lord K’an II’s initial defeat of Naranjo, around the year 626. Just as he invoked a militaristic god to initiate war, Lord K’an II takes pains to credit Snake Lord, a deity who guided his activities. The glyphs that document these events are located where Stela 3 is broken in half, so Zender could not read them as well as the others. But that brings us to another interesting chapter in this story.

The upper half of Stela 3 was discovered by University of Pennsylvania Museum archaeologists working at Caracol in 1950, in the midst of a multi-year project. At that time, DMNS was building a new archaeology hall, so it purchased that half of Stela 3 from the Penn Museum to put on display. In 1953, when university researchers returned to Caracol, they found Stela 3’s lower half a quarter-mile from where they found the upper half!

The government of British Honduras (now Belize) generously donated the upper half to DMNS. The reconstructed monument was showcased in 1956 and taken off display in 2000. But why was one half of the 8,000-pound stela found so far away from the other half?

Zender suggests that Stela 3 was destroyed around the year 680 by troops from Naranjo after they invaded Caracol. Stela 3 celebrates Naranjo’s defeat at the hands of Lord K’an II 50 years earlier. How could the soldiers from Naranjo not want to smash it? Remember when U.S. troops helped topple the statue of Saddam Hussein in April 2003? It’s the same behavior. Whether a statue, a stela, or a gate, a monument can be a symbol of power and privilege for one group and a threat to another.

If you had the resources and ego to build a monument to yourself, what would it look like? Would you create your likeness, as Arnold Schwarzenegger did when he commissioned three larger-than-life bronze statues of himself in a bodybuilding pose? Or would it be something that symbolizes your personality, like a bridge? What would you want it to project about you? What stories would it document? Would you construct it during your lifetime or have it built after your death? Would it honor yourself, a loved one, a group of people, or an ideal?

I think about these difficult questions when I walk through the Monti gate. And I must admit, I like Stela 3 a lot more than the gate. It was an active political document built and enjoyed during a person’s lifetime, and it tells an interesting tale. If I had a choice between the two, I’d rather erect a stela.

But I’m also reminded that people build different kinds of monuments, from works of art to businesses to pieces of writing. When I’m optimistic about digital technology, I dream that my Curiosities columns, now numbering almost 40, are a monument to my professional inquiry and output. When I’m pessimistic, I remind myself that the term “digital preservation” is an oxymoron and that one day the chronicles we create online will end up as forgotten as a ruined stone slab. But that’s a subject for another column.