Feeding Community When Government Aid Runs Dry

THE PRICE TO EAT

It’s the afternoon before the deadline for this article. I’m typing into Google: “How much does it cost to eat in Argentina?” The top results link to pages about the price of dining in restaurants in Buenos Aires, the country’s capital.

What I actually seek is the price of a basic food basket—the money needed per month to cover meals for a family of two adults and two children. The only accurate data comes from the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos, the institution in charge of Argentina’s census. On that June afternoon, the agency prices a food basket in Buenos Aires at $502.291 Argentine pesos (around US$.410). The minimum monthly wage set by the government is $308.200 Argentine pesos. I’ll let you do the math.

Since ultraconservative President Javier Milei took office in 2023, his policies have intensified Argentina’s economic crisis. In addition to experiencing job losses and frozen salaries, many people lack adequate food—sliding into what academics and humanitarian workers call food insecurity. The consequences of food insecurity—a focus of my research as a biological anthropologist—include malnutrition, chronic diseases, missed education, and later effects on the labor market.

In times of hardship, struggling Argentinians often turn to the comedores comunitarios or “community dining rooms.” Mostly run in churches or the private homes of women with few resources, these centers serve food to the most vulnerable. The comedores also create networks of support: They help people find solutions to situations of gender-based violence and family problems.

But under Milei, comedores comunitarios are also in peril. Unfairly accusing comedores of corruption, his government ended its state support for these vital social institutions. Without federal aid, comedores are reducing the portions and diversity of food they serve—just as more and more Argentinians need them.

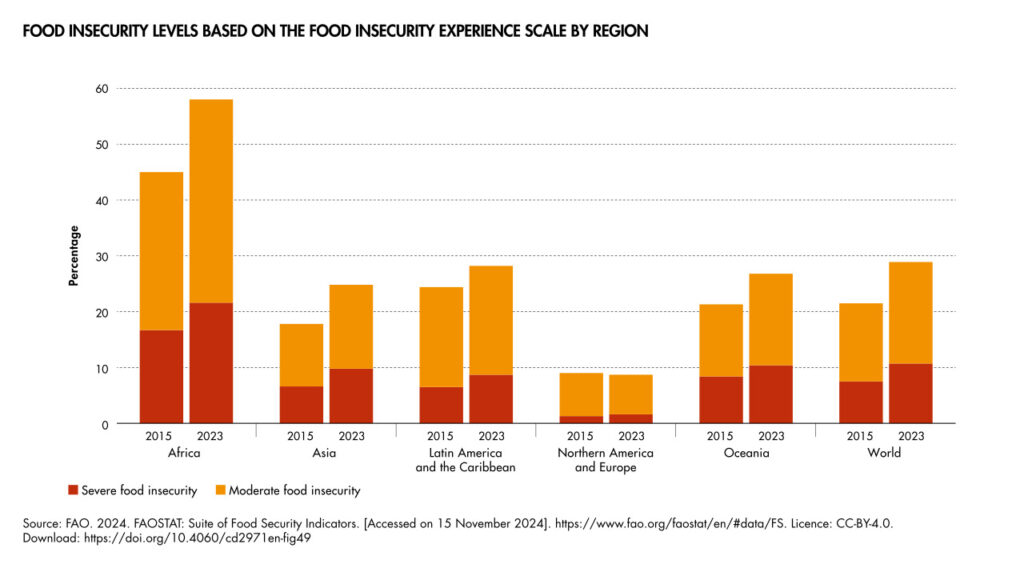

Argentina’s domestic cuts now coincide with slashes to international aid by countries including the U.S., Germany, and Canada. As governments eliminate programs that feed people, global citizens should understand the downstream effects of hunger and malnutrition—and how solidarity webs woven by institutions like the comedores act as a dam against the swelling tide of food insecurity.

FROM MILK TO MEALS

At the end of the 20th century, conditions had worsened in some places to the extent that it became essential to establish food as a fundamental human right. In 1996, the United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organization called this right “food security”—“access to safe and nutritious food” that meets people’s needs. In turn, chronic food insecurity was defined as the long-term, persistent lack of adequate food.

Many factors can lead to food insecurity: high food costs, low wages, unpredictable farming conditions, among others. I am interested in documenting how food insecurity impacts people in Latin America—both as a biological anthropologist who studies nutrition and as a person living in Argentina, where many lack sufficient food.

That’s why, one morning last summer, I sat down with Gladys Pérez, an Argentinian who has worked in a comedor comunitario for over a decade. As her poodle lounged nearby, we drank mate in her home in Puerto Madryn, a coastal city in the Argentine Patagonia. At some point neighbors interrupted, requesting her assistance with a neighborhood dispute. It seems Pérez also serves as the community peacemaker.

Comedores stand as a last barrier against hunger for Argentina’s most vulnerable.

Located in an evangelical church, the comedor where she works started by offering neighborhood children a glass of milk and organizing outdoor games. Over time, she and other workers realized that milk was the only nourishment the children had during the day.

So, the comedor started providing meals—first to 40 children, who later brought their mothers. Some older adults in the neighborhood also joined.

“In this place, people grab your hand thanking you because you gave them the food for the day. It’s people who save their weekend to eat,” says Pérez, tears welling.

That dining room is one of 30 comedores comunitarios in Puerto Madryn, home to around 120,000 residents. The number of comedores comunitarios in Puerto Madryn has been increasing since the pandemic. In May of 2021, as the COVID-19 pandemic peaked, Pérez’s comedor served 240 meals every day, the same number it dishes out now. To date, the team has served more than 70,000 meals.

RIPPLE EFFECTS OF INADEQUATE FOOD

Underscoring the importance of these meals, my research has detailed the adverse effects of inadequate food. Reviewing earlier studies that explored the link between food insecurity and health in Latin America, my colleague and I found that food insecurity can harm the body in myriad ways.

For some, the situation raises blood pressure or dips iron levels, which can cause anemia. People experiencing food insecurity may also be overweight or underweight, depending on factors such as gender, age, whether they are still growing, or a global process known as the nutrition transition—changes in diet and activity levels that often occur with globalization, urbanization, and economic development.

In Argentina and elsewhere, this transition involves shifting from traditional diets rich in fruit, vegetables, and whole grains to “Western” diets high in animal protein, saturated fats, and processed foods. People with lower socioeconomic status tend to eat more of the processed foods because they are cheaper.

Our work summarizing these outcomes may guide future research or policy decisions. But it does not put food on anyone’s table today. Places like the comedores comunitarios do—and it has become increasingly difficult for comedores workers like Pérez to meet this mission.

REAFFIRMING FOOD SECURITY AS A RIGHT

“To make a stew, we use 32 packets of pasta. For that many meals, we should use 15 kilos of meat, but we use 7 kilos,” says Pérez, expressing the difficulty of providing pricy protein in the comedor. Since Milei took office, food prices have soared due to the devaluation of the Argentine peso.

“Nowadays having light and gas in the house is more important than having meat,” she says, highlighting another irony: She lives in one of the world’s top meat-producing countries. This year, Argentina is breaking records for beef exports.

But this food is not reaching those in Argentina who need it most.

Soon after Milei became president, the National Secretariat of Children, Adolescents, and Family did not renew funding for comedores comunitarios. Now, to get government aid, people running comedores must complete a bureaucratic, costly application process, which requires legal status and accountant services. Consequently, most comedores quit applying for national funds.

These days, donations to cook the meals—mostly scaled down to just breakfast and lunch—come from neighbors, neighborhood businesses and bakeries, and local governments. Comedores stand as a last barrier against hunger for Argentina’s most vulnerable. It shouldn’t be this way.

Adequate food is a fundamental human right, which amounts to more than meals. Food security, which governments ought to guarantee, paves the way for people to have health, dignity, and a future.