When Biblically Inspired Pseudoscience and Clickbait Cause Looting

Update: May 6, 2025

We wrote this op-ed as a critique of the 2021 Scientific Reports paper titled “A Tunguska Sized Airburst Destroyed Tall el-Hammam a Middle Bronze Age city in the Jordan Valley Near the Dead Sea.” We argued that the paper was effectively pseudoscience, and we criticized the authors for promoting sensationalist narratives linking the site to biblical stories, essentially creating clickbait for the internet.The Scientific Reports paper was formally retracted in April 2025 due to significant concerns about errors in methodology, data analysis, and interpretation, as well as unsupported comparisons to the Tunguska event. The retraction serves as a significant reminder that sensationalist hypotheses—such as that catastrophic cosmic events destroyed ancient cities—require robust and reproducible evidence to avoid misleading narratives that can harm both scientific credibility and cultural heritage.

For myriad reasons, and like many other scholars working in Southwest Asia, we were profoundly disappointed when Scientific Reports, a peer-reviewed journal operating under one of the world’s leading scientific journals, Nature, published pseudoscientific research about a supposed ancient cosmic airburst destroying the Tall el-Hammam site in what is today Jordan. The authors speculate that this putative event may have been the basis for the biblical story of Sodom, in which a city was allegedly destroyed by stones and fire sent from the sky.

As of today, the original Scientific Reports story has been accessed 348,000 times and has generated nearly 20,000 tweets (including a retweet by astronaut Chris Hadfield, who has more than 2 million followers). It has been covered in 176 news outlets (including major scientific outlets, such as Smithsonian magazine) and was ranked 55th of the over 300,000 tracked articles of a similar age in all academic journals.

Much of the media attention seemed to us to be pushed by clickbait (sensationalistic text designed to entice readers to an article’s often dubious claims). For example, The Conversation article written by some of the study’s authors featured the enticing title “A Giant Space Rock Demolished an Ancient Middle Eastern City and Everyone in It—Possibly Inspiring the Biblical Story of Sodom.” The piece was widely republished, including in SAPIENS as “Did an Asteroid Shape This Famous Biblical Story?”—a clear tease.

What’s at stake when pseudoscience becomes clickbait? Many things, but we have time and space here to address only two repercussions: the erosion of scientific integrity and the destruction of archaeological sites.

First, this case exemplifies poor archaeological knowledge production. After the Scientific Reports article was published, the Twitter world caught fire. Scholars dissected the shoddy science, poor analyses of biological remains, edited images, overt religious agenda, and misinterpretations of stratigraphic contexts, particularly those exhibiting evidence of burning. This caused many to wonder about the vetting process and how such a flawed paper made it through peer review.

A leading scientist on asteroid collisions and airbursts, physicist Mark Boslough took to Twitter to deconstruct line-by-line the scientific errors in the paper. After scrutinizing the images used in the publication, Elisabeth Bik, a microbiologist and scientific integrity consultant, concluded: “Several photos of the dig sites appear to contain cloned parts, small areas that appear to be visible multiple times within the same photo.” She questioned the reasons behind the photographic alterations.

Biological anthropologists Megan Perry and Chris Stantis analyzed the interpretations of the human remains, noting that the examination was carried out by a medical doctor and not a trained bioarchaeologist. According to Perry, “MDs may know the basics of anatomy, but they generally are NOT experts in interpreting bone taphonomy or distinguishing between antemortem, perimortem, and postmortem trauma.”

Anthropologist Matthew Boulanger identified a serious flaw with the radiocarbon dates: “The date(s) reported reflect the a priori assumption that all of the 14C dates MUST represent a single event, and not (as presented) a test of whether the dates DO represent a single event. This is the definition of affirming the consequent, and it’s #badscience.”

Condemnation of this paper’s findings share one common element: Critics assert the data were made to fit a single hypothesis that Tall el-Hammam is biblical Sodom, even if the authors only dangle that connection in their articles and are careful not to make a direct claim.

For Steven Collins, the project director at Tall el-Hammam, and his team, the exercise of proving Tall el-Hammam is Sodom is the entire point of the endeavor. The goal of the work focuses resolutely on identifying Sodom, so it appears that all of the interpretation, communication, and fundraising of their work bends to meet that objective.

The team produces a high-profile, lucrative, clickbait storyline that they can deploy in a wide range of scholarly and public-facing venues. In the 2007 Wall Street Journal article “Digging for Sin City, Christians Toil in Jordan Desert,” Collins asserts that Tall el-Hammam is “ground zero for wickedness” and that the site would one day be a “a great tourist destination with a great big sign, ‘Welcome to Sodom,’ perhaps in pink neon.”

This WSJ article describes volunteers paying thousands of dollars to participate in the dig and notes that fundraising efforts appealed to fears of a post-Christian world. Collins states that he sought to verify biblical stories to challenge the “insidious little vermin of gnawing doubt about the credibility of the Bible. Christianity is lost in Europe because it lost faith in the biblical text. Post-Christian America is very, very close.”

Anyone who cares about archaeology, including scientists and scientific media outlets and the public who depends on them, should question the results of excavations that accompany claims like these made by Collins.

The age of archaeologists carrying a Bible in one hand and a spade in the other should rest in the past, buried in the colonizing archaeological practices of the 19th and 20th centuries. Today numerous rigorously scientific archaeological ventures investigate biblical time periods, yet none state they conduct their research to prove biblical stories as fact.

The vast majority of archaeologists working in the region do not believe that Tall el-Hammam—or the sites of Bâb adh-Dhrâʿ and Numayra, both traditionally associated with Sodom and Gomorrah—can be (or even should be) equated with these mythical biblical cities.

Instead, ancient peoples of the region likely developed oral histories and stories to explain these “ghost towns” located by the Dead Sea. Those stories then formed the basis for oral traditions that were eventually written down, more than a millennium later, in the Bible.

We have spent decades investigating and publishing on the Early Bronze Age (3600–2000 B.C.) urban communities of the Dead Sea Plain, while working tirelessly to dispel pseudoscience in the guise of archaeology surrounding the biblical story of Sodom and Gomorrah.

As anthropological archaeologists and critical thinkers, especially about heritage resources, we aren’t interested in equating real sites with mythical biblical cities.

We must reject work that inverts the established methods of archaeology and science. In science, researchers attempt to engage in objective investigation, following the evidence where it leads. Collins and his team members reverse this method, attempting to confirm a previously held belief. Their approach fuels pseudoscience.

The outcome of this pseudoscience is viral clickbait that resonates dramatically and rapidly outside of academia, regardless of any slow, measured, evidence-based pushback that would occur in a traditional academic discourse.

Fighting back against clickbait is not an abstract battle. Archaeological narratives highlighting connections to Sodom and Gomorrah exact real, physical harm to heritage resources and the people of Jordan through illegal excavation of sites associated with these mythical settlements.

While the authors of the Scientific Reports article assert that the issue of whether Tall el-Hammam is the biblical city of Sodom “is beyond the scope of this investigation,” mentioning Sodom multiple times and speculating about the connection produces insidious results.

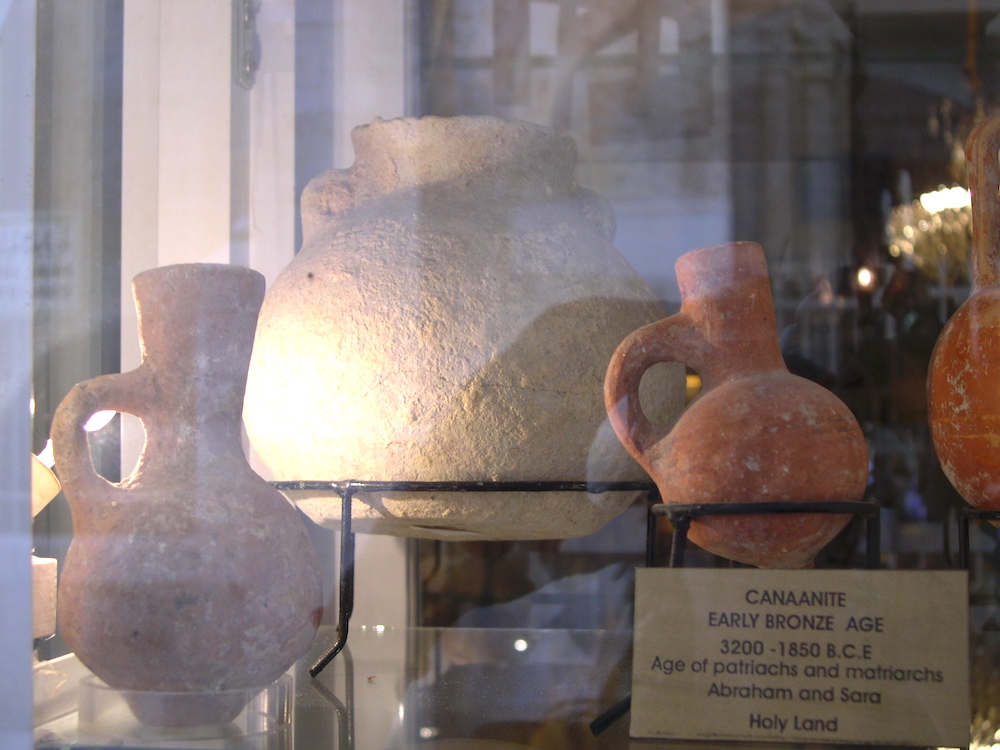

Illegally procured artifacts are marketed explicitly to people seeking a tangible connection with the Bible.

Sensationalized stories produced as a result of the original report accentuate biblical connections with archaeological sites, generating extensive hype. This increases desire for antiquities from these locations, and the rising demand results in looting.

Our Follow the Pots Project collaborates with Jordan’s Department of Antiquities to track how Early Bronze Age ceramic vessels buried with the dead are dug up from Dead Sea cemeteries, smuggled across an international border, laundered, and made available to consumers in legally sanctioned antiquities stores and auction houses. We use drones to document extensive damage caused by looting and conduct ethnographic interviews (with Institutional Review Board–approved protocols) with shoppers in Israel’s licensed antiquities market.

Buyers have explained their motivations for acquiring these objects by saying, I want “something from the time of Jesus,” “something related to the Bible,” or “a pot from the city of sin” (that is, the biblical city of Sodom).

The commendable efforts by the Jordanian Department of Antiquities to protect their past are often overwhelmed and stymied by the entrenched networks that launder illegally procured artifacts for entry into the legal marketplace, where they are marketed explicitly to people seeking a tangible connection with the Bible.

Yet when Boslough noted on Twitter that “pottery shards from Sodom and Gomorrah would have a much greater market value than shards from some random unidentified site,” Collins dismissed this salient concern, against all evidence. He responded, “Poppycock.”

Serious repercussions arise from looting these Early Bronze Age cemeteries to support demand for biblical touchstones. Grave goods honoring the dead are transformed into commodities available for purchase. Skeletal remains of once-revered ancestors are strewn across the pockmarked surfaces of these cemeteries—a fate these ancestors and their mourners never anticipated.

Destruction of these cemeteries obliterates possibilities for studying Early Bronze Age burial customs and human remains to gain insights into one of the world’s earliest urbanizing cultures.

Looting doesn’t just remove artifacts; it also destroys other less saleable materials and erases contextual evidence crucial to archaeological interpretation. Lastly, demand for these objects literally steals the cultural heritage of Jordanians, especially those living in communities near these cemeteries by the Dead Sea.

Demand-driven looting matters, and archaeologists, scientific journals, media outlets, and the public should never blindly and blithely support or foster these activities through clickbait claims based on pseudoscience.